Court Hearing Highlights Callous Incompetence Behind Medicaid Therapy Cuts

A Travis County judge has temporarily blocked the state from reducing funding for a Medicaid-backed therapy program for thousands of Texas kids with special needs, ruling on Tuesday that there was enough reason to believe the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) hadn’t done its homework before trying to implement the funding cuts and that the case deserved to be heard by a higher court.

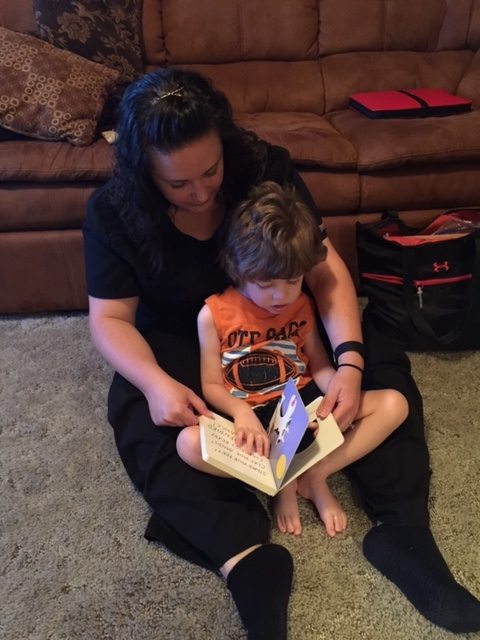

Earlier this year, when legislators took steps to slash around $350 million from the Texas Medicaid Acute Therapy Program, which helps provide access to occupational, speech and physical therapy for tens of thousands of children with special needs, advocates said the consequences would be disastrous — that the move would endanger children and worsen the quality of life for many of the state’s most vulnerable.

In recent months, advocates have also accused HHSC of failing to take even basic steps to ensure that the drastic cuts don’t cause undue harm. In court on Tuesday, Judge Tim Sulak agreed that there was reason to suspect HHSC hadn’t done the minimally required due diligence and that there had been a “credible showing of imminent and irreparable injury for the plaintiffs,” who risk losing access to health services. Sulak issued a temporary injunction to prevent the cuts, which would have become law on October 1, from taking effect until an appeal is heard.

His decision came after two days of damning testimony that called into question both the agency’s competency and lawmakers’ judgment when they slipped the cuts into a rider late in the budget-writing process.

The acute therapy program was, in some ways, an easy target for lawmakers convinced that Medicaid fraud and waste is rampant — a questionable premise, but one widely unquestioned in the Capitol — in part because information offered by HHSC made it seem like an easy target. The cost of pediatric services had indeed risen from $412 million in 2009 to a peak of $732 million in 2012, before dipping slightly. (Testimony offered by HHSC officials in court pegged the overall increase in Medicaid costs to the effects of the Great Recession.)

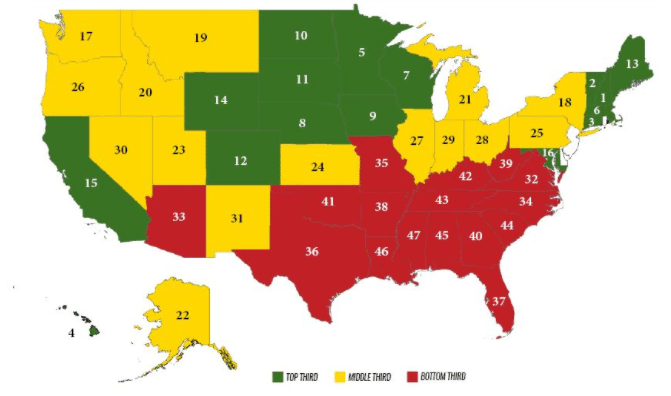

So the agency, and lawmakers, went looking for ways to save money last session. They attempted to compare rates for the provision of therapy services in Texas to the provision of services in other states. HHSC provided the agency’s findings in a report titled “Review of Texas Medicaid Acute Care Therapy Programs,” which they made available to legislators in February. Lawmakers read that other big states paid dramatically less for therapy services than Texas did.

The state’s position, remarkably, seemed to be that HHSC was not required to study the impact of cuts before implementing them.

But Ronald T. Luke, an expert in Texas health policy called to testify by the plaintiffs, said the analysis was “grossly misleading to the reader” and filled with elementary mistakes. “The numbers here are patently wrong and irrelevant,” he told the court, evidence of “people download[ing] stuff off the web that they didn’t understand.”

For example: Speech therapy represents a substantial portion of overall acute therapy cases. The packet HHSC provided lawmakers lists state reimbursement rates for different kinds of speech therapy sessions, including home visits, the most expensive at $137.20. Next to it are columns intended to provide comparison to other big states, but there’s no information at all for Arizona, Minnesota, or California. (See for yourself on page nine, here.)

The “review” suggests speech therapists in Florida are paid $17.86 per session. Even someone with no knowledge of health care policy should be able to recognize that number is wrong, or at least missing context, Luke testified: High-end therapy services offered by highly educated professionals, which involve travel to and from a patient’s home, cannot possibly be “worth” $17 per hour.

Other information used to compare Texas services to other states was incorrect or appeared without context. Luke even seemed to suggest the information was willfully misinterpreted. In parts of the analysis, numbers provided by HHSC used the median, rather than the average, of therapy costs, allowing HHSC to entirely exclude the most high-priced therapy services from their analysis and thus give a false impression that Texas therapy services were significantly overpriced.

HHSC has seemed to put some of the blame for the cuts and the ensuing controversy on researchers at Texas A&M University, who provided some raw data about Medicaid services in other states to the agency, along with a private company called Truven Health Analytics. Throughout the budgetary and rate-setting process, the agency and members of the Legislature have characterized agency conclusions as an “A&M study,” giving an academic imprimatur to the cuts.

On Monday, the state’s lawyers offered testimony that suggested A&M had even been asked to perform an analysis on the effect of Medicaid cuts, then failed to follow through with it. But on Tuesday, representatives for A&M told the Texas Tribune that the state was flatly wrong — and that, in effect, the state had lied in court.

The state’s lethargic defense of the cuts, provided predominantly by Eugene Clayborn, an administrative lawyer with the Texas Attorney General’s Office, consisted mostly of asking witnesses to restate their prior testimony. The state’s position, remarkably, seemed to be that HHSC was not required to study the impact of cuts before implementing them.

Tuesday’s injunction halts the cuts for now and gives the state time to find an alternate solution, if it so chooses. It’s a victory for the therapists and relatives of special needs children who filed suit to stop the cuts, but Dena Dupuie, one of the plaintiffs, said the close call was cold comfort.

“The evidence that came out during this trial is incredibly frightening — that HHSC would have pursued these cuts knowing full well that their own internal documentation says that it was going to brutally impact access to care,” she said. “I am not confident in the people that are making these decisions.”

Health care providers might not now be forced out of business after October 1, but she worried about the damage that the uncertainty might do to professional therapists as a whole. “I’m still nervous about what’s going to happen with these therapists,” she said. “I mean, are they going to see the writing on the wall?”

The state’s commitment to funding Medicaid, Dupuie said, seems to be in doubt, and health care providers, many of which operate with low profit margins, might judge the risk too much. One of her daughter’s therapists, who had been helping her deal with severe trauma issues, was no longer taking Medicaid, she said.

Another plaintiff gave testimony via telephone: Her daughter, who suffers from Rett syndrome, had been taken to the hospital the previous day. “Her whole body needs therapy to keep her from folding up and having contractions throughout her body,” she told the court. Any break in the provision of therapy services could have serious consequences for her health and future.

For years, Republican lawmakers in Texas have been asking the federal government for more control over the state’s Medicaid program, which operates under federal restraints. If the state hoped to demonstrate it had the competence to do so, the last several months have not been helpful to its cause. In court on Tuesday, it was clear that Texas has attempted to inflict grievous damage to the provision of crucial health care services in order to fund pet budget priorities at a very late stage in the budget process, and that it had based that decision on extremely bad math.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.