Closing Accounts

As the money runs out, hard choices in elder care

A version of this story ran in the March 2015 issue.

She’s naked from the waist up when we enter the room.

The sheet on her twin-size bed has slipped from the curve of her slight shoulders down to the small of her back—quietly hinting at the soft round flesh just visible beneath the cheap white bedding. She’s curled up in the fetal position, facing the wall. The bare skin of her back is taut and creamy, seemingly youthful despite its age.

I remember this moment only now, months later. At the time, I was distracted by the stench of urine, sour milk and a colostomy bag that desperately needed changing. My grandmother lay there, somewhere between unconsciousness and the painful reality of being awake. Her forefinger was curled up in the cord residents pull when they need a nurse. The tip of her finger was blue, but her fingernail was covered in a dingy brown film—so dirty that I reconsidered hugging her hello. Hovering at her bedside, I wondered how many days of accumulated filth it would take to turn my fingernail that color. The finger moved, slightly, rhythmically. She didn’t speak to us; we couldn’t help her. Instead, she intermittently mumbled what had become her mantra: “God, please help me. Help me please.”

A nurse’s aide from Green Valley Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center came into the room and helped get my grandmother out of bed and into a nightgown. It was lunchtime. My mother and I had brought her favorite meal, sparing no expense and withholding no calories: Grandy’s fried chicken with mashed potatoes, biscuits and gravy, fried cherry pie and Sprite.

During the last years of her life, my grandmother paid from $4,000 to $5,700 a month to live in facilities that she never called home.

The scene reminded me of feeding my daughter, Amelia, who was then just 2. Food always covered her chubby cheeks and dribbled gently onto her bib, the floor, and usually—somehow—found its way onto my shirt or into my hair. I took care of Amelia the same way my mom was now taking care of her mother. But while Amelia was getting stronger, more independent and more beautiful by the day, my grandmother, now 91, was fading away.

Love is not always pretty. For my mom, it was sad, depressing and, at times, disgusting. But love was always present: in every touch, in every decision, and in every forkful of fried chicken she fed to my grandmother.

This had been my mother’s life for the better part of three years, and it was taking a toll.

I wanted my grandmother to die because I wanted my mother to be able to live. And I hated myself for thinking that, until I realized that my grandmother wasn’t really living; she was just surviving. The person I remembered, cherished and respected was vanishing. And the most painful and saddest part of her life had become the most taxing to sustain.

AARP estimates that the cost to stay in a nursing home in Fort Worth, where my grandmother lived, is about $50,000 a year. That doesn’t include your own room. If you want privacy (read: no strangers or their families sitting beside you) you’re looking at about $63,000 a year, which is $12,000 more than the median household income for the state.

During the last years of her life, my grandmother paid from $4,000 to $5,700 a month to live in facilities that she never called home. That was more than she earned each month from her teacher retirement, Social Security, my grandfather’s pension and his Veteran’s Administration benefits combined. Luckily, she had some money saved, though it was never enough to last. Financially, she spent her last years always in the red.

She’d lived in two other facilities before moving to Green Valley Healthcare and Rehabilitation Center, which, I can assure you, was no green valley.

The first was by far the best. It was an independent living facility where my grandmother had something akin to an apartment of her own. She was still healthy enough to get around, and she took her meals in the cafeteria. She had friends. And game nights. And a little balcony with potted plants. She had chosen to leave her home of 50 years because she could no longer cook, clean or drive to the Kroger up the street—she no longer had the energy or the mobility. She moved her furniture and her photos to decorate the small one-bedroom unit, and she hosted throngs of visitors, family and friends acquired over the course of a well-lived life. She came out to attend our family Christmas celebration, birthday parties and Easter. On Sunday mornings she took her seat on the right side of the church sanctuary, alongside the fragile, white-haired widows with whom she’d shared dance halls and bingo nights in another life.

But independent living facilities are often just the first step in an inevitable decline in quality of life. And they aren’t cheap, either. My grandmother paid nearly $32,000 a year to live at The Wellington, a well-manicured and cheerful facility located in suburban Fort Worth. Such facilities are designed for people who don’t necessarily need a nurse nearby. They can eat and go to the bathroom on their own, and maybe even drive, as many Wellington residents did.

When seniors get to the point where they need access to a nurse or a nurse’s aide every day (or every hour), it’s time to move out—and come up with a lot more dough.

When my grandmother fell out of her bed for the fifth time and broke her hip, at age 90, she began to need more help than independent living could provide. So my family decided on a nearby nursing home and rehabilitation facility called Life Care Center of Haltom. She hated it, and she hated to leave her apartment at The Wellington. Moving to The Wellington had been her choice. She had been in control. And up until the last few months of her life, she held out hope that she would be able to return to that apartment with the potted plants and the 1960s-era barrel chairs in the living room. But we all knew there was no going back, even if we didn’t have the heart to tell her.

Most Americans don’t know what their end-of-life care choices even are. Lack of education and failure to make clear decisions lead to emotional strain on families and medical costs that can be impossible to manage.

That cost, of course, is for what my mother described as “private pay people.”

“If your [monthly] income is $2,000 or less, you qualify for Medicaid and you live there for just $2,000 a month,” my mom said. She had become quite the expert on Medicaid and Medicare coverage, out of desperate necessity. My grandmother’s income was $3,000 a month, which was too much to qualify. “And that’s terrible,” my mom said, “because she had to pay top dollar everywhere she lived.”

According to a report released last year by the Institute of Medicine, most Americans don’t know what their end-of-life care choices even are, and the subject of death and dying often isn’t discussed until it’s too late. That lack of education and failure to make clear decisions lead to emotional strain on families and medical costs that can be impossible to manage.

In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that there are 15,700 nursing homes in the United States with a total of 1.7 million beds. There are close to 76 million baby boomers (people from the ages of 51 to 69) living in the United States today. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, that’s about a quarter of the country’s population—people who over the course of the next 20 years will require the type of care that my grandmother couldn’t afford.

By the time my grandmother was settled into Life Care Center of Haltom, she was racing through her cash reserves like a teenager in a sports car.

My parents rented out her house for $750 a month. That helped, but she was still short—by a lot. They sold her car and cashed in most of her investments, but it was like putting a Band-Aid on an amputated limb.

After the first year in the nursing home, my family decided to sell her house and use the proceeds to pay her rent at Life Care.

Of course they didn’t tell her they were selling her house. Her home. They couldn’t. She had lived there since her 30s. She had raised five children there. Hordes of grandchildren had taken over rooms, turning couches into forts, beds into playgrounds, and a two-car garage into a pingpong championship arena.

As children, we had spent sticky summer days in that garage, our backs pressed firmly into faded plastic chairs, our dirty fingers wrapped tight around Blue Bell ice cream cups and half-empty Dr Pepper cans pilfered with greedy gusto from the garage refrigerator placed there with grandkids in mind. That was Maw-Maw Betty’s house.

Inside her small, shared room at Green Valley Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center, the air was hard to breathe. A thick layer of Lysol failed to mask the odors seeping from shriveling bodies dependent upon others for life.

There were no grandkids there but me. It was a soul-sucking experience, and I immediately wanted to erase it from my memory. But it stuck, like my bare skin to those plastic chairs in Maw-Maw Betty’s garage all those summers before.

When I was a child, my grandmother was plump and perfect. She laughed easily, prayed daily and favored sky-blue sweaters and cardigans with delicate floral patterns—loose clothes that concealed the colostomy bag she required after surviving colon cancer when she was 71.

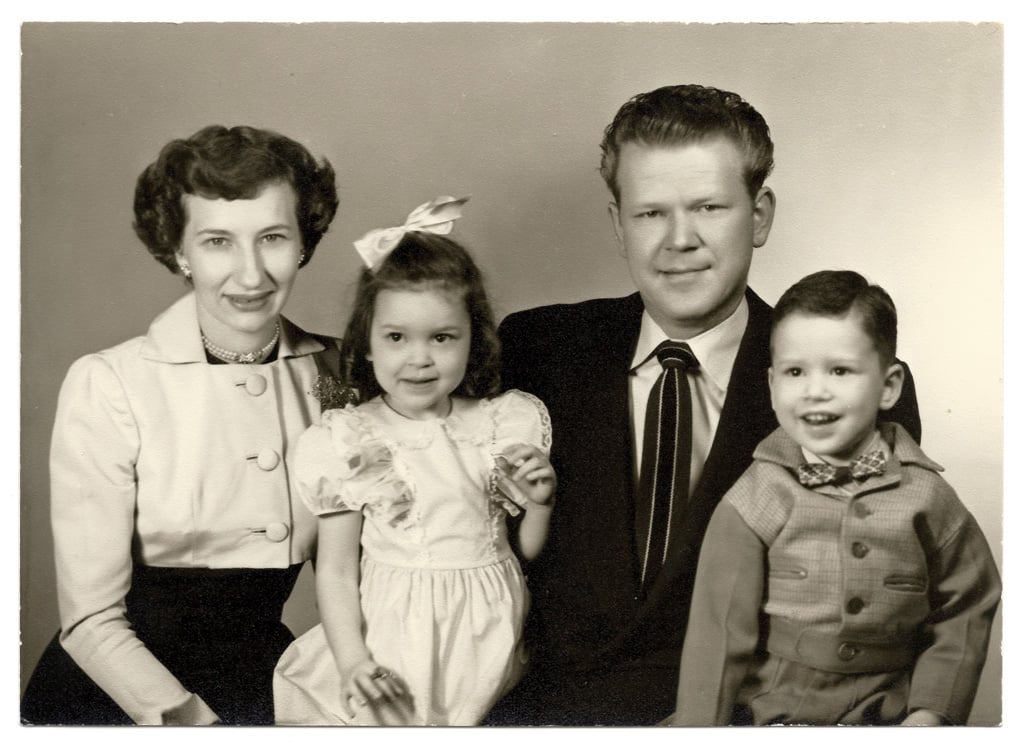

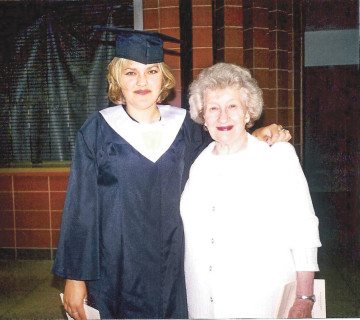

During the last years of her life she used a walker. Just a little bit at first, and then all the time. Finally, she gave the walker up for a wheelchair. But her brilliant mind remained—the same mind that had decided, decades before, when she had just gotten married, to raise her new husband’s two children as her own. My mom was one of those children, just a toddler when Betty became her new mother.

The next time I saw my grandmother, two months after my last visit to Green Valley, her fingernails were freshly painted the most delicate shade of pink. She even had on her coral Estee Lauder lipstick. She was thinner than she’d been, smaller all over, lying in a casket at the front of the church she’d attended her entire life.

As I sat in the wooden pew of the church she’d known so well, I promised myself that I could cry for hours—for days—but only after I finished reading her eulogy.

I didn’t dare tell the crowd that I was glad she wasn’t suffering anymore. That nothing—not friends, family or even money—could have saved her from the incredibly lonely process of dying. Or that the cost of caring for her during the last years of her life had sucked away every penny she had so diligently saved.

I didn’t say any of that. Instead, I just wished my grandmother were still alive as I watched my mother cry.