Childhood Lost

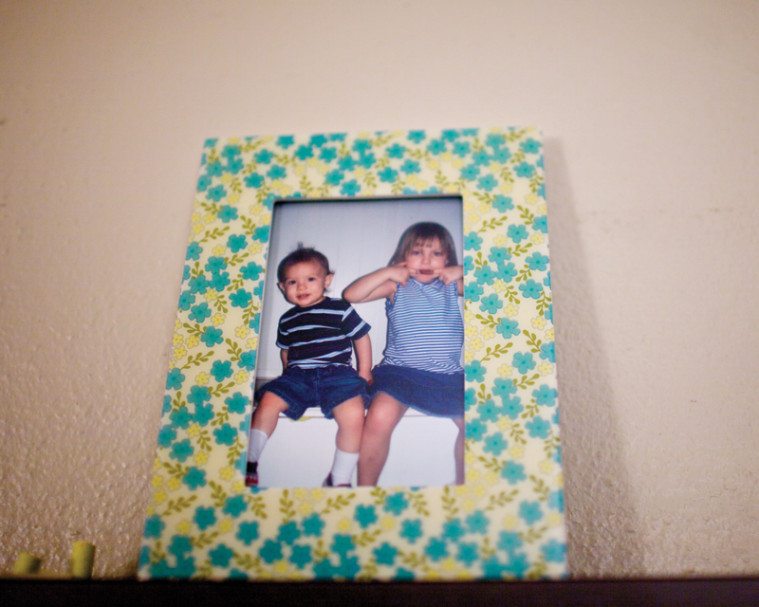

Sarah Brian says her two children were stolen by her own parents—with help from the state of Texas.

A version of this story ran in the May 2014 issue.

On a warm day in March 2009, with her face on “Wanted” posters around town and Nacogdoches County Sheriff’s deputies hunting for her, Sarah Brian put some pretzels in a bag, buckled her 13-month-old son into his stroller and went for a walk.

Sarah and her son, Avrahem, were joined by her ex-fiancé Adolfo, an oilfield worker often gone for work or locked up in jail, but he’d returned to Sarah’s life a week earlier. They’d argued, as usual, when he showed up at her apartment. After the fight, Adolfo called Sarah’s parents, with whom he’d become close, to tell them that Sarah’s behavior seemed erratic, and that he thought she and Avrahem looked too skinny.

Sarah didn’t know he’d contacted her parents, and she and Adolfo had set aside the previous week’s fight—like so many arguments before—as they strolled down the streets of Nacogdoches, past old tire shops and the park along Bonita Creek. They’d nearly reached Main Street when a sheriff’s car approached and, with a quick woop of its siren, spun around to cut them off. The deputy got out and told Sarah to put her hands on the car. More sheriff’s office cars soon surrounded them, and then Sarah’s father, Mark Brian, pulled up. Her father had sworn out a mental health warrant on her. As Adolfo looked on, the authorities tucked Sarah into the back of a car, chained at the ankles and with a leather strap around her waist. “I kind of felt like Hannibal Lecter,” she says. She could only watch as an officer wheeled Avrahem away and gave the child to her father.

After a time, a deputy sat down in the driver’s seat, and he and Sarah began the 40-minute trip to Rusk State Hospital. Despite the drama of the previous few moments—the surprise arrest, the emergency detention warrant alleging Sarah’s grave instability and having just seen her young son taken away—in video from inside the car Sarah appears calm. On the way to her court-ordered psychological evaluation and possible commitment, Sarah and the deputy pass the time with small talk.

“Have you been to Rusk before?” the officer asks her.

“Mmhmm,” Sarah says. “They’ve done this to me before.”

There’s disagreement in any legal fight, and in family law the arguments are especially personal. Sarah and her parents have widely different versions of her story. But there is no clear evidence that Sarah has ever harmed her children. In that sense, Sarah’s story is an important marker of the thin standards by which the state—through small-town judges—can take a child from a parent, even without specific allegations of wrongdoing. For seven years, Sarah was separated from her children by temporary orders signed by the only family judge in town.

Born the day after Christmas 1981, Sarah grew up in a brick ranch-style home at the end of a quiet Nacogdoches cul-de-sac dotted with pines. Her father was an executive for an East Texas logging firm and her mother was a homemaker. Sarah, the second of three children, was a mild-mannered student who found religion as a high school freshman, played tenor sax in the high school band and took Baptist missionary trips in the summer. She started a Christian club in her high school called “Generation J,” and was shocked the one time she was sent to the principal’s office because she wore a T-shirt—it read, “I Like Blue Grass”—that seemed like a pot joke.

She had chronic pneumonia as a child and often had trouble sleeping. When she was in seventh grade, Sarah was hospitalized for an overdose of Benadryl. Sarah says she accidentally took too many pills. In court records, her father contends it was her first attempt at suicide: “It was determined that my daughter was suffering with depression, perhaps caused by the onset of puberty/adolescence. … Thereafter, Sarah’s life was rocky and unstable.” Having graduated from high school and aged out of her youth groups, Sarah bounced between churches and struggled to find a new crowd. She hung out with artists and musicians in Nacogdoches who drank and smoked pot. She still lived with her parents, who’d long regarded Sarah as unique among their children and didn’t approve of her new lifestyle.

Sarah’s recollection of her own life diverges significantly from her father’s account in the four-page affidavit used to arrest her, especially about her mental health. Mark Brian says his daughter was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2002, and prescribed medication she quit taking after two years. After her Benadryl overdose, the affidavit details four more suicide attempts: three more overdoses on medication and the last, at age 22, by cutting her wrists. Sarah says the overdoses were accidental, and that she never wanted to kill herself. Her bipolar disorder, she says, was an armchair diagnosis by a friend’s father, casually confirmed later by her mother’s psychologist, and repeated by her parents at each subsequent hospital visit. From age 19 to 22, she says, she was heavily medicated with antipsychotics. At various times in those years, she was prescribed Seroquel, Lamictal, Risperdal, Zyprexa, Tegretol, Carbatrol and lithium for bipolar disorder; Paxil and Lexapro for depression; and Foradil, Albuterol and Singulair for asthma. “There are times in there I just don’t remember,” she says. “I do remember waking up and my dad would hand me more pills, and I’d pass out again.” At one point, she lined up her pill bottles side by side and counted them, all the way to 17. “It was a shocking moment, and it really scared me,” she says. From then on, she stopped taking the pills, she says, except an asthma medication and a sleep aid.

Sarah made a few other attempts at breaking away from her parents. She enlisted in the Marine Corps in 2002, but was discharged after a month—because, she says, she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder tied to physical abuse she endured at home as a child. Her father, who has repeatedly denied her abuse allegations in court, says she was discharged because doctors discovered she’d been diagnosed as bipolar. The next year Sarah enrolled at Wharton Junior College, outside Houston. She says her father once drove the 200 miles to surprise her on campus, showing up and yelling outside her dorm that he was worried about her and begging her to take her pills. At Wharton, she met a man named Manuel, whom she married in January 2004. She left school and the two moved into her parents’ home. Her new husband quickly turned abusive. Though Sarah called the police for help several times, she says, her parents laid the blame on her. In one particularly dramatic incident discussed often in court, she says, Manuel fired a gun in the front yard during a fight, and he was arrested. Mark Brian says Sarah was the one who was arrested after firing the gun, pointing it at her chest and saying she wanted to die. A police report about the incident confirms that they’d been fighting, but doesn’t mention arrests or a gun. They’d been fighting, the report says, because Sarah was upset that Manuel had an ex-girlfriend’s name tattooed on his arm.

After a little less than a year of marriage, Sarah and Manuel separated, and she met Adolfo about a year later. In between, she became pregnant and her first daughter, Annunziata—she called her “Zoe”—was born in July 2006. Sarah and Adolfo raised the girl together, along with one of his children from a past relationship. They moved into an old house he owned in his hometown of Raymondville, planning to fix the place up. When Sarah’s parents came to visit, the “unsanitary conditions” impressed Mark Brian enough to warrant a mention in a later affidavit.

Adolfo blew in and out of Sarah’s life, and by spring of 2007 she had moved back in with her parents, a single mother living in her childhood home. In May that year, after a fight with her mother—Sarah says her mom hit Zoe—she decided she’d had enough. As Mark Brian later explained in a court document, “My daughter scooped up her daughter and a few personal things and left our home on foot.”

This stew of domestic strife became the people’s business a few days later, when Mark Brian filed a suit affecting the parent-child relationship—or SAPCR—in the Nacogdoches County Court at Law. He saw Sarah’s decision to leave as a troubling return to the erratic behavior of her past. Mark Brian declined to speak with the Observer for this story, but in court transcripts and personal correspondence he appears desperate to protect his family, worried for Sarah’s well-being, but certain Sarah can’t live safely on her own without medication. He was faced with a choice, he figured, between leaving his granddaughter in danger with Sarah, or using the law to keep the young girl safe—at the risk of inciting another of Sarah’s suicide attempts. “It was the most agonizing thing that any father would ever have to do, because you were totally manic,” he told her months later in court. “Who do I sacrifice? That’s been my hell.”

The county court issued a warrant to have Sarah arrested, though the warrant was based on thin evidence. Under state law, such a warrant must reference “specific recent behavior” suggesting “substantial risk of serious harm to himself or others; [and that] the risk of harm is imminent unless the person is immediately restrained.” But Mark Brian offered little specific evidence suggesting substantial risk. After describing Sarah’s history of mental illness and suicide attempts years earlier, her father mentioned only Sarah’s abrupt departure from home, yet that was enough to convince the local judge there was “imminent risk.”

Armed with the mental health warrant, deputies caught up with Sarah in town, seized Zoe, who was delivered to Mark Brian, and took Sarah to Nacogdoches’ Memorial Hospital. Sarah spent hours in the hospital handcuffed to a wheelchair before attendants came in, stripped her clothes off and dressed her in a hospital gown. She was examined by Dr. James Buckingham, who’d been her mother’s psychologist and had consulted with Sarah after an alleged overdose. He recommended she volunteer for commitment and resume taking her pills, and during the hospital exam, still reeling from the swift loss of her daughter, Sarah also learned she was pregnant. Frightened as she was for Zoe, she was overjoyed at the thought of another baby. Sarah left the hospital, against Buckingham’s advice to voluntarily commit herself. Nothing in her behavior warranted that the hospital force her to stay. She hurried back to her parents’ home to rejoin her daughter, from whom she’d never before been separated.

As a 25-year-old woman who’d grown convinced that her parents were trying to control her, Sarah saw her arrest and her daughter’s removal as stark displays of just how little power she had in her hometown. The court order mandated she was allowed to be with Zoe only if one of her parents supervised. But they fell gradually back into their old routines, Sarah making Zoe’s organic baby food in the kitchen and taking her daughter out for walks. Sarah and her parents often had heated fights over parenting questions—like whether the girl should eat peanut butter—letting Sarah’s father decide.

She placated her parents, they later claimed, by scheduling an evaluation with a doctor in Shreveport, Louisiana, later in 2007, but secretly she planned her escape. On the computer at home, while she watched her daughter and her mother watched her, Sarah discreetly researched other cities—weather, support networks, work prospects—and settled on Flagstaff, Arizona. Pictures of its forests and hills even reminded her a little of home.

One weekend in September 2007, Sarah and her daughter boarded a bus and made the 20-hour trip to Flagstaff, taking a cab to a women’s shelter when they arrived. She left behind no notice of her plans, other than a note saying they’d gone to Dallas for the weekend. Against the urging of a counselor at the shelter, Sarah called Adolfo, told him where she was and asked him to join her. They lived in a motel together for a while, looking for a home to move into. But at some point either Adolfo or his mother told Sarah’s parents where they were.

One night a few days before Christmas, Sarah answered the door—not knowing her cover was blown—to police with a court order to reclaim Zoe from her. She tried in vain to explain the messy history behind the decisive court order—that it was just her parents’ play for power, that she was perfectly safe living on her own—but a woman officer grabbed her daughter and took off running to a parking lot nearby. Shuffling across ice and snow, two weeks from giving birth to Avrahem, Sarah chased after Zoe until she saw the officer stop beside a rented PT Cruiser, where her father took the girl.

“They made me go pack her bag and they wouldn’t let me make contact,” Sarah says. “I didn’t see her for a year after that.”

Sarah spent weeks draining calling cards to reach lawyers in Flagstaff or Nacogdoches, a trying time interrupted only briefly by the birth of her son, Avrahem. No attorney would take her case. “They’d say, ‘Why don’t you get off drugs first,’” she says, “or they’d quote me like $300,000.” Instead, she taught herself what she could about the law at Flagstaff’s law library to prepare for a hearing back in Texas that she’d finally been granted.

Texas is one of the nation’s least generous states for grandparents who hope to sue for access to their grandchildren. Grandparents’ rights are a well-developed corner of family law, covering anything from intra-family squabbles that the grandkids don’t visit enough to complaints from grandparents who’ve witnessed child abuse. A wave of new laws expanded grandparents’ rights in the 1990s, but were swiftly rolled back after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2000 decision in Troxel v. Granville. The ruling instructed courts to rule with “a presumption that fit parents act in the best interests of their children,” and to give “special weight” to parents’ decisions for their children, even over grandparents’ objections. In the last 10 years, the Texas Legislature has curtailed grandparents’ rights even further, spurred on by a vocal minority of parents who want to home-school their children over their own parents’ objections.

The legal standard for grandparents to win “managing conservatorship” of a grandchild in Texas is demonstrating that “the child’s present circumstances would significantly impair the child’s physical health or emotional development.” That’s a high bar, according to family lawyers, but it’s also vague enough to vary widely from one judge to the next.

Donate now to support independent, nonprofit journalism.“It’s a problem a lot of times in what we do, is that people will throw things out there with the implication being that this is a danger to the children,” says Sherri Evans, a Houston attorney who chairs the family law section of Texas’ state bar. “There are perfectly healthy, loving, fabulous parents that have some sort of diagnosis. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard somebody say, ‘They can’t have custody because they’re taking antidepressants.’”

Though Texas law presumes it’s better to keep a child and parent together, no judge wants to be known for returning a child to a dangerous home. The law uses phrases like “imminent risk,” and “significant impairment” of a child’s “emotional development,” terms that don’t translate simply into real, messy lives. It’s up to judges to decide what they mean.

For more than a decade, Jack Sinz has been Nacogdoches County’s Court at Law judge. He’s run unopposed since his election in 2002, and is the arbiter of small-time drug cases, domestic abuse, and family law. Like most small Texas counties, Nacogdoches doesn’t have the luxury of specialty courts. With a slim face, wire-rimmed glasses and short brown hair, Sinz has a genteel Southern bearing behind the bench. But to Sarah, Sinz, the man who already signed off on a warrant declaring her dangerously ill, the man who stood between her and getting her daughter back, was an intimidating presence. Sarah studied his court, sitting on a back bench to watch him decide other cases.

In late January, she walked into the Nacogdoches County Courthouse for her hearing—her first chance to challenge in court her parents’ indictment of her parenting—and sat down alone at a table before Judge Sinz with her hand-written defense and a few notes on legal procedure. She figured it would be simple enough to demonstrate that removing her daughter was just a mistake. Taking the witness stand, she related her side of the story at length. She denied nearly everything her father had contended, though the most dangerous thing her father had suggested was Sarah’s continued denial. As she recalls today, she was in a difficult spot: “How do you prove that you’re not crazy?”

After her father testified to his concerns, Sarah had the chance to try out her new cross-examination skills. Somewhere in her research she picked up the tip that she’d have to phrase everything as a question, so she repeatedly began inquiries with, “Isn’t it true that…”

With her father under oath, Sarah asked him just what prompted him to take her to court.

“It is just the same pattern of denial that you have a problem, or there is any problem at all,” he replied.

“And how is that dangerous to my child?”

“At any moment you can go completely manic and attempt suicide again.”

In a series of questions, Sarah asked him to admit to hitting her as a child, which he repeatedly denied. “There is nothing to apologize for,” he told her. Later, her sister agreed there’d been no abuse in their childhood home.

An official from Child Protective Services testified that—while the agency had cleared Sarah of her parents’ allegations of neglect—he had personal concerns about “the mother’s past mental health issues, and her denial of having mental health issues.”

Facing such stark disagreement, Judge Sinz left the temporary order in place and called for a psychological examination by Dr. Thomas Allen of Tyler to determine whether Sarah could safely care for her daughter. “And he may say you are fine, no problem,” Sinz said. “He gives that opinion and has done everything he can, and says you present no risk or problem to the child, I would have no choice but to go with that.”

Dr. Allen did his due diligence: a two-hour consultation with Sarah, a three-hour written diagnostic, interviews with Adolfo and other family members, and a review of the evidence supplied by Sarah and her parents. Dr. Allen returned a glowing review of Sarah’s mental health and fitness to parent. In a letter to Judge Sinz dated March 24, 2008, Allen explains that Sarah showed no signs of bipolar disorder or other mental illness other than depression consistent with the lonely, protracted legal fight to reclaim her daughter. Though Sarah “may have” been suicidal in the past, he writes, nothing suggested she was anymore. “I find no indication that Sarah Brian is a risk to herself or her child for any sort of violence or neglect,” Allen writes, before suggesting how unnecessary the proceedings seem to him. “It appears Mary and Mark Brian do not like or do not approve of some of Sarah’s decisions. Welcome to parenthood.”

Allen’s evaluation might have been the last word; after all, the court-ordered assessment had found Sarah fit to get her daughter back. But in June 2008, Sarah’s parents urged the judge to weigh the report against Sarah’s troubled past.

Judge Sinz had ordered the release of Sarah’s medical records, including notes from two suicide attempts and two week-long stays at Brentwood Hospital in Shreveport. They detail Sarah’s 2002 overdose on lithium, Risperdal, Paxil and Jack Daniel’s, and the night in 2004 when she cut her wrists. According to the notes, Sarah told hospital staff she’d tried to kill herself, and that the medication for her bipolar disorder wasn’t working anymore. All the incidents took place years earlier, well before Zoe was born, but they suggested Sarah was still an unreliable narrator of her history.

The Brians’ attorney, Beth Brice—a well-respected family lawyer who taught at Stephen F. Austin University—insisted Dr. Allen couldn’t have grasped the depths of Sarah’s problems in a single meeting. She called Dr. Buckingham, testifying over the phone, to recount Sarah’s past suicide attempts, and again assert her history of bipolar disorder. (Sarah says she asked Buckingham’s office for copies of those records, both before and after his testimony, but was refused.) He urged Judge Sinz not to rule on Dr. Allen’s letter alone. “In consultation, Sarah can be quite charming and quite good to be around, and does come across very well,” Buckingham said. “I’m sure I’ve had a number of patients who fooled me too.”

With Buckingham testifying by phone, Judge Sinz grasped to understand just what sort of danger Sarah poses to her child.

“Does she have any condition that would lead her to do something like drown all her kids in the bathtub or horrible things like that?” Sinz asked.

“I don’t have any reason to think that,” Buckingham replied.

“In other words, she wouldn’t go and try to burn her kids with cigarette butts or pull out their finger nails or anything like that?”

“I don’t know about that,” Buckingham said. “I worry too about the psychological—quite aside from the physical—which is very hard to measure.”

Sarah took the opportunity to refute Dr. Buckingham’s testimony by calling up Dr. Allen to defend his positive evaluation of her. The hearing’s professional veneer broke down as Sarah asked him to address the judge’s earlier questions.

“Do you think that I would do something horrible,” she asked, “like drowning my children?”

“I’m sorry, Sarah. I think you started crying, and I couldn’t understand you,” Allen replied.

She repeated the question, asking if she was a risk for physical or psychological harm to her daughter.

“I don’t think you’re going to do any more damage than the average parent to your children, just being normal human beings.”

In cross-examination, Brice asked Dr. Allen whether Sarah could have gamed her way to a clean bill of health. “Is there any possibility that she may have pulled the wool over your eyes?” she asked.

“Probably not,” he replied.

“Have you ever had that happen since you have been practicing?”

“Only by lawyers.”

As he weighed the word of two conflicting experts, Sinz offered a window into his thoughts on the case. “I will say this,” Sinz told Allen, “just for your information, obviously Sarah’s parents say that she is not truthful and upfront about things. Dr. Buckingham says she is not truthful. The Child Protective Services caseworker says she’s not truthful, after making his investigation. And her own sister says she is not truthful, and her parents are. So we got a lot of people saying Sarah misled them and doesn’t tell the truth. I’m not saying you’re wrong about it, but a lot of people are saying she has a problem with owning up to her problems.”

“For me, judge, it is a matter of what actual evidence is there that makes her a risk to the children,” Allen replied. “That’s the threshold that I have to go by in the Family Code. If I thought she’s a risk to the children, I would say so.”

Nine months passed, and Sarah heard nothing about her case. Then came March 2009, when Judge Sinz signed off on a second mental health warrant, and another temporary order, this one removing Avrahem to join Zoe with Sarah’s parents. When the deputies caught Sarah on her walk in Nacogdoches, she was heartened in a way, because it meant another day in court. While riding in the back seat on the way to Rusk State Hospital, she explained to the deputy, “If anything, this is good luck for me, because it’ll just prove that I am mentally sound.”

Sarah was right: The state’s psychologist at Rusk didn’t share Nacogdoches County’s sense of urgency about Sarah. An evaluation report describes her as having “allegedly been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, although given her present presentation right now, she does not appear to be either manic nor depressed. … Really at this time she does not appear to have a mental illness diagnosis at present.” The hospital refused to treat her. Sarah caught a ride with the deputy back to town.

She returned home to a quiet, empty apartment surrounded by her son’s things. She’d lost her son just as she lost her daughter, but she was convinced that this time would be different. Not only had another professional verified her mental stability, but this time she had a lawyer of her own.

After months of cold-calling law offices, Sarah reached Amy Long in Lufkin, who’d just started her own family practice. She went by the office and was amazed by Long’s reaction when she related her tale. “She was screaming and cussing and, ‘How dare they?’” Sarah says. “She was the first one that treated me like a human being.”

Long recognized Sarah as someone on the fringes of the legal system—with enough income to pay her bills, but not enough to pay a lawyer’s. Nacogdoches’ legal aid attorneys, overworked as ever, hesitate to take on messy, drawn-out family cases. And when the high-dollar family attorneys come in, typically they’re more evenly matched—fighting over shares of a big estate, for instance. Families without that kind of money tend to settle things less formally. “There is a massive group of marginally indigent folks who simply lack access to the courts,” Long says. “I still believe that the system works when pressed. It’s just very expensive.”

Though Long’s new solo practice was still struggling, she took on Sarah’s case for almost nothing. Sarah saved money from her shifts at Taco Bell and began selling cookies online to help cover some of Long’s expenses.

On April 1, 2009, just over a week after Sarah lost her son and was turned away from Rusk, Long filed a motion to dismiss the suit on behalf of both Sarah and Adolfo, claiming the Brians were holding their grandson illegally, and that they’d been unjustified in swearing out a mental health warrant against Sarah. Long claimed the Brians didn’t have standing to bring their suit in the first place, because they couldn’t prove that the children were in any real danger.

In a hearing later that month, Jeremy Willis made his first brief appearance as the appointed attorney ad litem for the children. Based on his interviews with both sides, he explained in a letter later, he’d decided the grandchildren would be better off with the Brians than with Sarah and Adolfo. He suggested a schedule for visitation, and a new hearing to plan “a six month schedule to permanently re-unite Abverhem Satoshi Conde and his parents.” (Sarah says her parents misspelled the boy’s name in their lawsuit, and the error stuck.) Reuniting Avrahem with his mother, he writes, is “critical for [his] well-being,” but he says Sarah would have to show good faith by getting treatment. Willis writes, “There is overwhelming evidence as to Sarah Brian Munoz’ mental illness and it is my opinion that her failure to accept this illness places Abverhem Satoshi Conde at risk.”

At the end of the hearing, Willis agreed to “investigate the parties further” and report back soon. Instead, in August Willis asked to withdraw from the case. Though he apparently never signed off on the request, Judge Sinz wrote both parties in November, demanding Willis be paid the $1,000 he was owed. It was the last filing in the case for more than three years, and Avrahem was never appointed a new attorney. Meanwhile, the case sat in limbo, the judge scheduled no new hearings and the temporary custody orders remained in place. The first temporary order, which gave the Brians custody of Zoe, would remain in place for nearly six years. Without a final order, there was nothing for Sarah and Long to appeal. They were stuck in Sinz’s court. Years passed and the children grew up.

Sarah’s long fight for custody of her kids doesn’t conform to established practices. When Texas’ Child Protective Services temporarily removes a child from the home—typically after a complaint from a neighbor or some other non-family member—state law provides a timeline for resolving the case, and a presumption that the child should be reunited with its parents, if possible. The so-called plan of service that a parent must complete varies widely from case to case, but comes with a 12-month deadline, and a maximum extension of six months. The law recognizes that too much time away from a parent changes the relationship. However, custody suits from grandparents don’t come with this deadline.

In hearings, Sinz repeatedly explained the tough standard the Brians had to meet. “The law requires us to protect parental rights rather than even grandparent rights,” he explained to the Brians at one point. “My job is really to protect the freedom and the rights of parents to raise their children, unless there is some serious problem or concern.” But his temporary order in favor of the Brians became less temporary with every delay in the case. June Clifton, Judge Sinz’s court coordinator, was familiar with the case when I asked her about it recently. Though she wouldn’t go into specifics, she said a number of factors held up Sarah’s case. One factor was that Willis apparently never got paid, and he was never replaced with another attorney ad litem. Sarah says she filed motions that went ignored. In June 2012, the Brians’ lawyer, Beth Brice, died.

While she waited for word on whether she could be trusted with her children, Sarah got a job at her church day care center, looking after strangers’ kids. Twice a week during this stretch, Sarah walked across town from her apartment to a visitation center to spend the court-ordered two hours with her children, before returning them to her parents’ care. She bought them new clothes when the things they wore looked too small. She took photos to document the mold she found in their sippy cups. Sometimes, she says, she’d walk miles across town to wait in the visitation room, but her children would never come.

Thresa Caldwell, a social worker who supervised Sarah’s visits, says she was impressed by Sarah’s parenting skills and her desire to care for her kids. “Sarah is very special to me and so are her three children. Sarah’s case was and is unique in that it involved the idea that persons with mental illness are not ‘fit’ parents,” she says. “I have witnessed many parents who are diagnosed with a mental illness who are great parents. These parents may or may not be medicated, they may or may not be under the care of a therapist, yet they manage to be great parents.”

In 2010, Sarah learned she was pregnant again. Rather than risk losing yet another child to her parents, she left town. She abandoned her apartment, where she’d kept a playroom ready for her kids’ return. Leaving meant no more visits with her two oldest children; she hasn’t seen either of them since. She refused to give her parents any hint of where she was. She lived for a time in Temple, where she found work at a community nonprofit and gave birth to her daughter, HalleluYah Zion Eve. She returned to Flagstaff for a while, where she found a comfortable life working for a raw-food advocacy group. Most of all, she awaited the day her two oldest could return.

In May 2012, frustrated by the slow pace of the proceedings, Long attempted a legal end-around on the Nacogdoches County courts, suggesting Sarah file for divorce from Manuel (which she hadn’t yet done) in another county. By law, any child custody suit from another county would have to transfer to the county court of the divorce proceeding. Sarah had a friend in Wichita County, so she moved there long enough to establish a residence and filed for divorce.

In January 2013, Long wrote to June Clifton asking why Judge Sinz hadn’t yet granted the transfer, which, as far as Long was concerned, should have been a simple matter of paperwork. In response, Judge Sinz held a new hearing in March 2013, at which Long was surprised to learn that Sarah’s divorce had just been finalized. Sarah, still in hiding, wasn’t there for the hearing, but James LoStracco—the district attorney’s husband and one of the county’s most expensive family lawyers—explained the divorce had been closed in February, so there was no longer any need to transfer the children’s cases.

Sarah, not expecting any news in her divorce before the custody suits transferred, hadn’t been checking her post office box in Wichita Falls. Manuel had hired an attorney and asked for a final divorce decree; when Sarah didn’t respond, the judge finalized it without her. Sarah and Long remain convinced the Brians orchestrated the move to keep their custody suits from leaving Nacogdoches County.

Long was irate, but as she saw it, her last avenue of legal attack had been cut off. Having shepherded Sarah’s case for nearly four years, working for little pay and getting nowhere, she withdrew from the case. “I had to withdraw,” Long says. “Do I think that she has been done dirty? Hell yeah. Has it been done in a wrong manner? I believe so. But I am a little solo practitioner attorney. I can’t afford to front a case that takes this kind of time, energy and effort. And not be paid—she has paid me a little bit when she can.”

Over the years, friends have occasionally asked Sarah why she isn’t trying harder to get her kids back, baffled that it could have taken her so long. “I lost faith in the court system pretty early on, after it was totally shattered by Sinz,” Sarah says. Instead, she refocused her efforts outside the local system. She called the Texas Rangers, the FBI and city police, hoping to get someone interested in her cause. “Everyone said that just given the amount of time, it didn’t matter who had rights, possession was in favor of my parents,” she says. She began saving money to buy transcripts of the court hearings, to help file a formal complaint against Sinz with the State Commission on Judicial Conduct. She printed off a complaint form and carried it around as a reminder. HalleluYah has decorated it with little blue squiggles around the border.

People naturally often ask her what her daughter’s name means. Sarah asks them if they have time to settle in to hear the story of her two older children, the ones she hasn’t seen in years. HalleluYah, she says, is a sign of her faith things will work out for her in the end: “Even though this is the worst time in my life, I’m saying praise God now.”

As she told her story, she encountered other women whose children were taken years ago, or who are in court now trying to regain their rights. Sarah plans to start a nonprofit group to help mothers like her, and she’s embraced a wider message of fighting to regain some measure of power in small Texas counties where the courts have become blunt tools of the powerful few. “My kids are going to grow up and know that their life is incredibly valuable,” she says, “and I had the guts to stand up for not only them, but other families too.”

On Feb. 20, Judge Sinz at last signed final orders in the case, naming the Brians the “sole managing conservators” of their two grandchildren. There is no transcript of the January hearing that decided the case, and in the end, it was Sarah’s fault she missed it. Still in hiding to keep her parents from discovering where she and her youngest daughter live, she hasn’t been checking her post office box in Wichita Falls, where the hearing notices would have been sent. Sarah at least now has a final order to appeal, though that will cost money. And she now has new financial burdens.

In the final orders, Sarah, along with each of the children’s fathers, is named a possessory conservator. That gives her some limited rights spelled out in state law, like the right to see her children’s grades in school or check their medical records. The fathers can see the children alone if the Brians agree, but Sarah can visit them only under her parents’ supervision. Beginning in February, she now owes her parents $350 a month for child support. The fathers owe nothing.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.