Border Lawman Tells Texas Politicians to ‘Shut Up’ About the Border

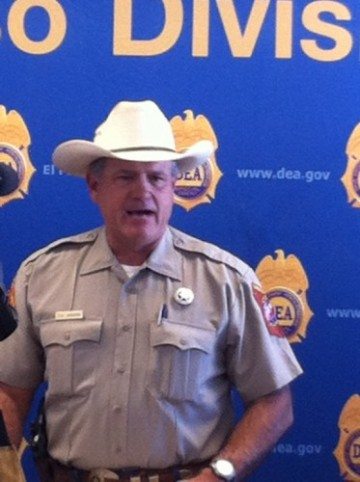

Above: Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst tours the Rio Grande on a well-armed DPS boat

We’re in the middle of an election season that has seen a lot of political posturing over the Texas-Mexico border.

Considering only the lieutenant governor’s race: Dan Patrick has been railing about the state’s “illegal invasion” and the constant threat of violence posed by migrant criminals; David Dewhurst wants a $60 million “permanent surge” of manpower, vehicles and high-tech hardware, even if the Texas Department of Public Safety will have to cut other programs to do it. Todd Staples has spent years as agriculture commissioner talking about border security, and now he’s toting around a “six point plan” to finally lock down the Rio Grande. (Though one of those six points is “secure our border,” so it may not be the most comprehensive plan.)

One long-time border sheriff wishes they’d all just pipe down about it.

Brewster County Sheriff Ronny Dodson, who’s held his post for 14 years, is the chief law enforcement officer in Brewster County, the largest in the state—five times the size of Rhode Island, three times the size of Delaware and 500 square miles larger than Connecticut. It also has the largest stretch of the US-Mexico border of any Texas county. You might think, when it comes to the border, that he’d be ready for Dewhurst and Patrick to hurry on down and exact some Texas Justice. You’d be wrong.

“A lot of politicians are running on securing the border. One’s got a six point plan, one’s got a nine point plan. They’re throwing tons of money at this border. I wish they’d just shut up about it.” he told me. “Recently, we had an operation where they sent game wardens out here to look for drug traffickers—game wardens! I guess they figured the game was secure.”

Dodson’s family has been in Brewster County for five generations. In the early 1900’s, Pancho Villa’s rebels ran his grandfather off his ranch, and the family had to relocate to a protected basin in the Chisos Mountains. Compared to that, the border now looks tame—certainly not the way politicians in Austin are talking about it.

“I think they’re just throwing money at the border for nothing. I think people on the interior see all these shows about the border where there’s violence,” he says. That’s a problem for places like Brewster County, the home of Terlingua, Lajitas and Marathon, where tourism comprises a large part of the local economy.

“A lot of tourists will call up to my office and say, ‘Is it safe out there?’ We’ll ask where they’re coming from. They’ll say ‘Houston,’” he says. “We’ll say, hurry up and get out of there! It’s safer here than where you’re coming from.”

A lot of border lawmen, Dodson says, are happy to take money from Austin. “I’m guilty myself of taking quite a bit of that money,” he says. With it, his men are better paid, better resourced. “We have equipment now because of that money that we would never have otherwise.”

But the increased state focus on border security comes with a cost, Dodson says. It drains resources from other causes, and it makes people feel insecure. And besides, he’s not really sure whether it’ll do a damn bit of good.

“They were smuggling across the border when my grandmother was a girl, and they’re going to be smuggling when my granddaughter grows up,” he says. “I wish they’d stop talking about the border and focus on problems in the interior.”