Book Report: El Paso on Lithium

A version of this story ran in the September 2015 issue.

The Confederate flag waving in the brisk wind on a 6-foot pole in the bed of the white pickup in the apartment complex parking lot seemed not so much an endorsement as an invitation to fight. The bubba who parked it there and nailed an “Only Trucks Allowed” sign outside his apartment door could have been willing and able to shoot anyone who knocked to complain. So I sat in my car for a couple of minutes, pondering options. Confronting him would be pointless. I drove away. That’s the way it is in Texas nowadays. That sad realization is one of the many things that drew me into the violent, lunatic landscape of Rick DeMarinis’ new crime novel, El Paso Twilight. What at times in this solid chase-adventure can seem almost like cartoonish hallucination in fact reflects real-time social devolution. The novel’s stereotypical goons and thugs turn out to be like the people around us. Its sadists, murderers, crackpots, militia dudes and bounty hunters freely shooting up the populace are the stuff of TV news and reality shows. No big deal. It’s just the way it is.

Except, at times, to J.P. Morgan, the Anglo protagonist of DeMarinis’ numbed-out, over-medicated and doggedly existential slice of contemporary reality in the legendary border city. As J.P. navigates his way through each day into his own twilight, he knows it all comes to naught, but he plays it out anyway. Born an ordinary West Texas kid, he has been through the chaos of Iraq, a failed marriage and personal upheavals, and now he’s watching the outsourcing of his comfortable gig as an insurance fraud investigator.

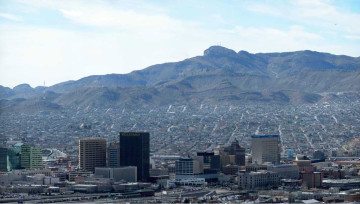

The city he calls home gives him the space he needs to create his own justifications for who, why and where he is. DeMarinis, a professor emeritus at the University of Texas at El Paso, who, before moving back to Montana, ran in circles that included his neighbor Cormac McCarthy, infuses the novel with a fine sense of a complex place: “American civilization in retrograde,” J.P. says of El Paso. “The town looks modern enough — freeways, the usual glass and steel buildings, the usual shopping malls, the usual briefcase-carrying men in thousand-dollar suits giving the impression of vitality and purpose — but deep within its poetic heart it nurtures a secret desire to apply the brakes to the machinery of enterprise. It’s a poor town … but the ambitionless feel comfortable here. My father went against the grain, and it killed him.”

J.P. is convinced that El Paso owes its retrograde spin to the lithium salts naturally occurring in the groundwater of the Hueco Bolson aquifer. That’s one of the reasons he rails against water-wasters and is not averse to sneaking onto a homeowner’s property to turn off sprinklers. He has also developed a perverse if not icky fascination with cockroaches, whose endurance in that middle-of-nowhere city evokes something important, probably.

By Rick DeMarinis

Bangtail Press

$29.95;449 pages

264 pages;

$17.95 Bangtail Press

Self-mired in historic Sunset Heights, J.P. drives an old Monte Carlo, favors cheap breakfast joints and absorbs the city as it is. Same way he absorbs the malevolence pushing his friends toward what anyone can see is a bad end. “We have plenty of crime,” he observes, “but the professional crooks are generally laid back and not entirely convinced they are the bad guys. If I said I loved the place, I’d be misstating the facts,” J.P. says. “I am the place: Articulated chaos. Me.”

As is often the case in crime novels, J.P.’s troubles start with trying to help a friend obsessed with a woman. In this instance, one who has disappeared. The friend is Luther Penrose, a 6-foot-2, 290-pound self-styled intellectual and writer who might pass as a Trans-Pecos cousin of A Confederacy of Dunces’ Ignatius J. Reilly. But way more debauched. While finishing his impending masterwork, Gotterdammerung Now, on a 1926 Underwood Standard typewriter, Luther has learned that his activist wife, Carla, an instructor at UTEP, has left with Hector Martinez, a handsome young Chicano. Luther prevails upon his lifelong friend to find out. Turns out J.P. has some free time anyway, because the corporate insurance company for which he works has decided to contract out its in-house investigative services to a flashy security firm. Naturally, that firm is corrupt and slimy. In his “paranoid logic,” Luther hires the firm as a backup to J.P., who thinks Luther’s whole plan is crazy. Which it is. Thus does a simple missing persons gig turn into a meat grinder.

Turns out Hector is wanted by a few more people, from the corporate skip tracers to a self-styled militia known as the HBB (Hans Brinker Brigade), which wants to start a war with Mexico. It’s hard to tell the lumpen thugs apart, because they’re pretty much the same — “stern and regimented and eager to inflict pain.” They go named and unnamed: HBB psychos Huddy Darko and Spode Weem; skip tracers known only as Little Big and Extra Big. “For big boys they didn’t make the floor squeak much,” J.P. observes of the latter two.

The novel’s stereotypical goons and thugs turn out to be like the people around us. Its sadists, murderers, crackpots, militia dudes and bounty hunters freely shooting up the populace are the stuff of TV news and reality shows. No big deal.

The HBB’s financial backer is a revenge-obsessed, right-wing, sadistic plastic surgeon whose son was accidentally killed by Hector. Perhaps these characters are not ripped from today’s headlines, but they’re recognizable enough. We know these kinds of people. We see them hoisting racist flags in parking lots.

J.P. tries to move between the villains he is chasing and the ones chasing him, with limited success. He and Luther both are brutally beaten, and they both end up blowing away some of their assailants and railroading another into a dire fate in a Mexican jail. “It occurred to me,” J.P. reflects at one point, “that what I was about to do was not in my self-interest. It also occurred to me that I didn’t have a clear idea anymore of what was in my self-interest or even what ‘self-interest’ meant. Maybe the self had its own agenda and I was its vehicle. A familiar but disturbing thought better left alone.”

After connecting with Carla and Hector, J.P. learns that their trip is no simple lovers’ getaway. They’re on the lam because they are conspiring to retrieve a half-million dollars liberated by a friend of Hector’s in Iraq and smuggled into the United States. They want to put the money to good use for various social causes. J.P. tells them they have no chance at succeeding and probably will be killed, but his efforts to talk them out of their fantasy fail. Which is bad news for them both. Hector in particular.

Throughout this narrative, the backstory is the ongoing struggle in J.P’s soul. By the time the case is solved, he has tried to work through flashbacks from Iraq, his mother’s mental deterioration, Luther’s loose grasp on reality, and his own debatable life choices. Bottom line: He has not so much moved forward as dug in. “This is my place on the planet. This is all I know,” he concludes. As proof, he removes his mother from a nursing home, and her caretaker turns out to be a young Mexican woman he rescued from drowning in the Rio Grande. It’s a symbolism he can’t overlook. For all the hell he’s been through, he says, “good things happen.” In what one hopes will be a sequel, that will almost certainly be disproven, and J.P. has told us why: “I’ve seen enough unmoored behavior by otherwise respectable citizens to make me think that most people are mentally adrift in one way or another.”