As Seas Rise, Texas Pretends It Isn’t Happening

In the August issue of the Observer, I wrote a cri de coeur (I can’t pronouce that phrase but it works) on climate change denial in Texas, posted online this week. The response from some of our readers was interesting, and it’s one that I hear more frequently from progressive-leaning folks: Climate change is real, it’s caused by humans, but it’s too late to do anything about it, therefore all we can do is adapt.

I don’t subscribe to the view that it’s ‘too late’ to avoid what you might term “extreme” climate change, mainly because I tend to rely on the mainstream views of climate scientists. But it is very much true that some warming is inevitable. In fact, over the last century the planet has heated 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit over land. Because of past and present inaction, more climate change is ‘in the pipeline’ and is inevitable. The reality of some degree of climate change, and its myriad consequences, does militate for adaptation. Plenty of nations and some American states get that, and are making plans now. What about Texas?

Texas Climate News, which is a well-reported, just-the-facts-ma’am publication sponsored by the Houston Advanced Research Center offers a perfect example of the head-in-the-sand approach prevalent here: The ongoing development of Galveston’s low-lying West End even as beach erosion, subsidence and sea-level rise conspire against it. I wrote a lengthy story on this topic back in 2007. It seems not much has changed.

After navigating the complexities of Galveston building codes, builders like Mullican, who specializes in large, beachfront residences, believe their structures are capable of standing up to hurricanes, the rising sea and erosion.

“All these fearmongers that are saying we shouldn’t build here, we shouldn’t build there, the water is coming up. To me, it’s Chicken Little,” said Mullican. “We can build timeless buildings and deal with what comes.”

Scientists studying the Texas coast have taken a different stance.

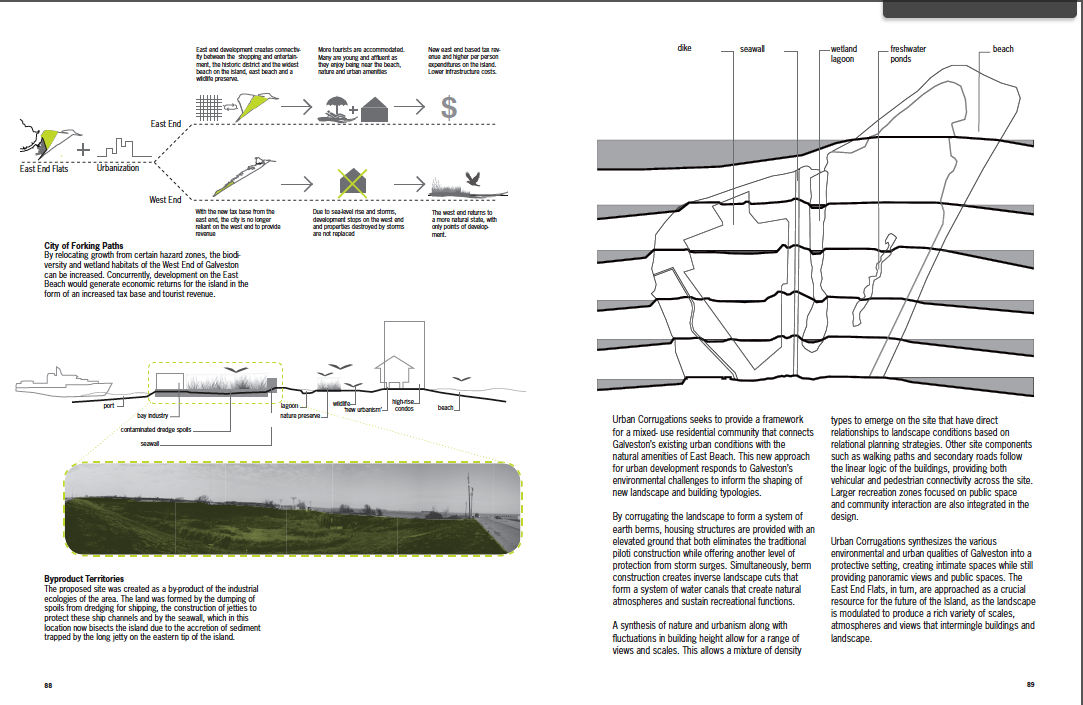

John Anderson, a Rice University oceanographer, suggests a fundamental shift of development must take place. Growth, he says, should move from the West End to the East End Flats – a large, unpopulated area on the eastern side of the island, currently owned by the federal government and used to store dredging material. Near Galveston’s historic downtown, the East End Flats is protected by the island’s famous seawall and did not flood during Hurricane Ike, unlike the West End.

This represents, to some extent, an old coastal conflict: the retreatists vs. the stand-your-grounders, those who would bend to Mother Nature and those who would defy her. But what’s different now is both the scale and speed of the challenge. While Galveston, famously, is vulnerable to hurricanes and beach erosion, inexorably rising oceans pose an existential threat. How do you build a “timeless” condominium capable of withstanding not just the occasional Hurricane Ike (or worse), but several feet of sea-level rise? And, more important, should you?

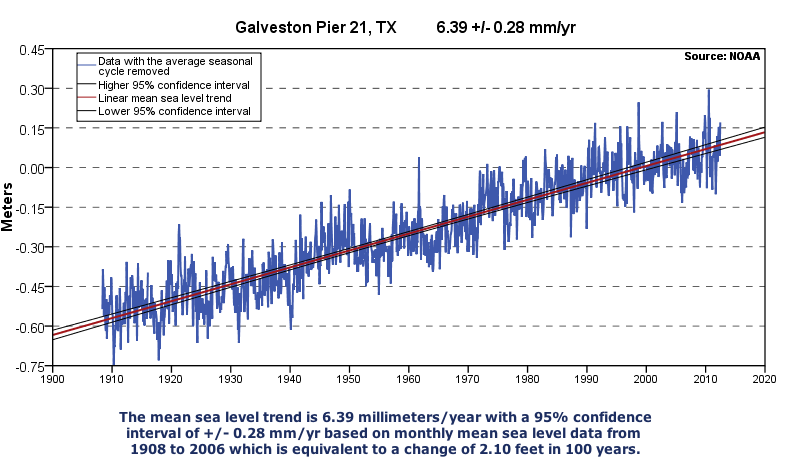

The eastern third of the Texas coast has some of the highest relative rates of sea-level rise (rising oceans plus sinking land) and beach erosion in the nation. The beach is retreating on the western end of Galveston at a healthy clip of three to six feet per year. Tide gage records at Galveston’s Pier 21, dating to 1908, show that the Gulf has risen about 6.4 millimeters per year over the last century.

That may not sound like much, but even if that rate holds steady (a very unlikely scenario), Galveston is facing another foot of sea-level rise by 2050, and almost two feet by 2100. A more likely scenario, given the thermal expansion of the oceans due to more heat and melting ice sheets and glaciers, is possibly on the order of several feet by the end of the century, according to many scientists using the most current data.

In 2009, scientists with the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies in Corpus Christi studied the impact of sea-level rise on the Galveston Bay region for the Environmental Defense Fund. They considered several scenarios. At just .69 meters (2.3 feet), a conservative estimate for 2100 according to the authors, 78 percent of the households in Galveston, Harris and Chambers counties would be displaced from their homes and the area would rack up $9.3 billion in economic losses. At 1.5 meters (4.9 feet), 93 percent of households would be displaced and $12.4 billion of losses would be incurred.

This is not a message that many want to hear, including supposedly science-driven state agencies. Recall that the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality went so far as to censor Rice’s John Anderson last year, when he turned in a book chapter that discussed the latest science on sea-level rise.

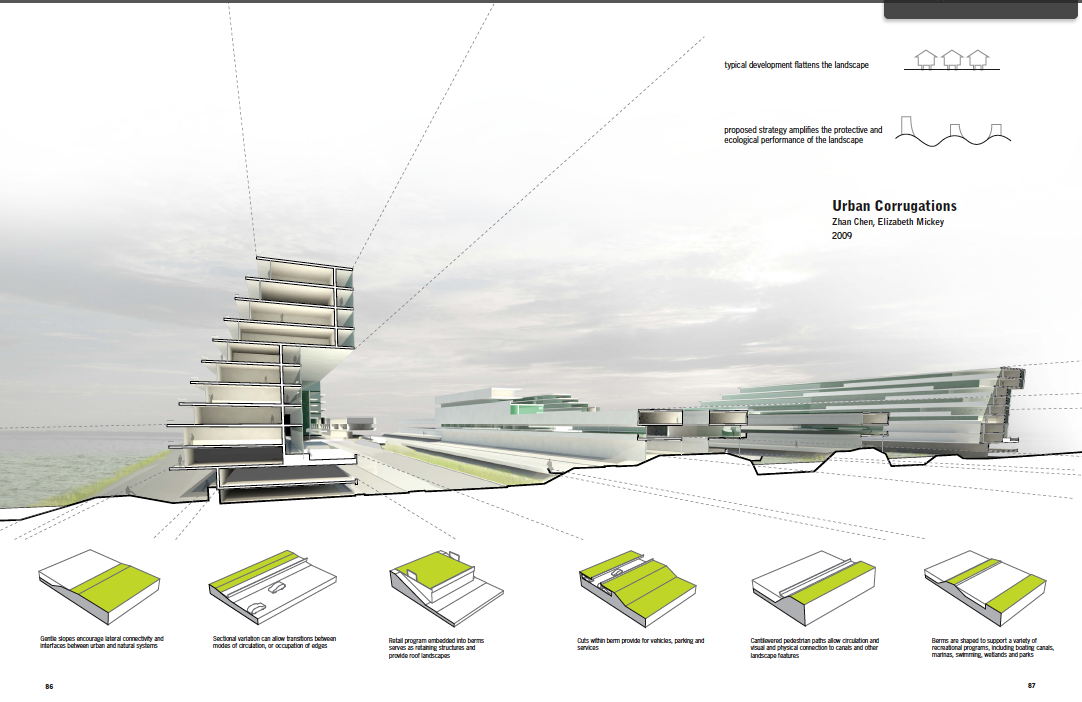

What folks like John Anderson are promoting is, in a sense, much less naive than continuing business-as-usual: refocusing the location and character of development to allow for an orderly accommodation of nature. In 2010, the Rice School of Architecture imagined how Galveston could reinvent itself, and not just survive but thrive, in the face of a grim future. The students came up with some wild stuff.

Meanwhile, the developers chafe at what they see as onerous regulations holding them back.

The primary tool for development policy on Galveston Island is flood insurance rate maps created by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Rate maps determine which areas are most likely to flood and who must have flood insurance. The city government uses the rate maps to regulate building in flood prone areas, and banks use them to determine who must have insurance before they lend money, according to FEMA.

Building specifications are guided by the International Building Code and residential codes. The City of Galveston does add amendments that are stricter than those standard codes.

Mullican believes the current regulations are too stiff and the cause of Galveston’s slow, post-Ike recovery. Ike caused more than $20 billion in damage and lowered the island’s population by several thousand. The population has not yet rebounded.

“The city of Galveston has been primarily responsible for the lack of growth on Galveston Island, not the fear of building and not nature itself,” said Mullican. “It is the city of Galveston that is preventing us from standing back up and rebuilding this city because of all the restriction and the delays.”

There is, of course, an economic case to be made for laissez-faire in the aftermath of a disaster. But, then, what about the long-term accounting for costs? Who pays to protect an island besieged by the seas? Since Hurricane Ike, there’s been talk in Galveston of building the Ike Dike, a massive public works project that would require New Deal-style funding and chutzpah to carry out.

Some folks point to The Netherlands as a nation that’s used ingenuity and engineering miracles to turn back the seas. But if you think the United States, in this current area of tea partying and austerity madness, is capable of that then I’ve got some oceanfront property in Arizona I’d like to sell you.