In late 2010, Dr. Christopher Duntsch came to Dallas to start a neurosurgery practice. By the time the Texas Medical Board revoked his license in June 2013, Duntsch had left two patients dead and four paralyzed in a series of botched surgeries.

Physicians who complained about Duntsch to the Texas Medical Board and to the hospitals he worked at described his practice in superlative terms. They used phrases like “the worst surgeon I’ve ever seen.” One doctor I spoke with, brought in to repair one of Duntsch’s spinal fusion cases, remarked that it seemed Duntsch had learned everything perfectly just so he could do the opposite. Another doctor compared Duntsch to Hannibal Lecter three times in eight minutes.

When the Medical Board suspended Duntsch’s license, the agency’s spokespeople too seemed shocked.

“It’s a completely egregious case,’’ Leigh Hopper, then head of communications for the Texas Medical Board, told The Dallas Morning News in June. “We’ve seen neurosurgeons get in trouble but not one such as this, in terms of the number of medical errors in such a short time.”

But the real tragedy of the Christopher Duntsch story is how preventable it was. Over the course of 2012 and 2013, even as the Texas Medical Board and the hospitals he worked with received repeated complaints from a half-dozen doctors and lawyers begging them to take action, Duntsch continued to practice medicine. Doctors brought in to clean up his surgeries decried his “surgical misadventures,” according to hospital records. His mistakes were obvious and well-documented. And still it took the Texas Medical Board more than a year to stop Duntsch—a year in which he kept bringing into the operating room patients who ended up seriously injured or dead.

In Duntsch’s case, we see the weakness of Texas’ unregulated system of health care, a system built to protect doctors and hospitals. And a system in which there’s no way to know for sure if your doctor is dangerous.

–

Up until 2003, medical care in Texas was regulated by a system of checks. Hospital management, the court system and the Texas Medical Board formed a web of regulation that penalized and prevented bad care.

But in the past 10 years, a series of conservative reforms have severely limited patients’ options for holding doctors and hospitals accountable for bad care. In 2003, the Republican-dominated Texas Legislature capped pain-and-suffering damages in medical malpractice lawsuits at $250,000. Even if a plaintiff wins the maximum award, after you pay your lawyer and your experts and go through, potentially, years of trial, not much is left.

The Legislature has also made suing hospitals difficult. Texas law states that hospitals are liable for damages caused by doctors in their facilities only if the plaintiff can prove that the hospital acted with “malice”—that is, the hospital knew of extreme risk and ignored it—in credentialing a doctor. But the Legislature hindered plaintiffs’ cases even more by allowing hospitals to, in most cases, keep credentialing information confidential. In effect, plaintiffs have to prove a very tough case without access to the necessary hospital records. This is an almost impossible standard to meet, and it has left hospitals immune to the actions of whatever doctors they bring on. Hospitals can get all of the benefit of an expensive surgeon practicing in their facility and little of the exposure. This has freed hospitals from the fear of litigation, but it’s also removed the financial motivation for policing their own physicians.

The medical malpractice cap and the near-immunity for hospitals snapped two threads from the regulatory web. What remained was the Texas Medical Board.

But the Medical Board wasn’t designed to be an aggressive enforcer. It was mostly designed to monitor doctors’ licenses and make sure the state’s medical practitioners are keeping up with professional standards. The board’s mandate, spelled out in the Medical Practice Act, recognizes a doctor’s license as a hard-won, valuable credential. Doctors’ rights are to be protected at every step of the process. The board can’t revoke a license without overwhelming evidence, and investigations can take months, with months or years of costly hearings dragging on afterward. The protections make some sense. The Legislature doesn’t want the Medical Board taking a doctor’s license—and livelihood—unnecessarily or based on flimsy or frivolous claims. But the result is that unless a doctor is caught dealing drugs or sexually assaulting patients—or is convicted of a felony—it is difficult to get his or her license revoked.

What all this means is that the Texas Legislature has committed the state to a policy of medical deregulation—a free-market system in which doctors can practice as they please with limited government interference. Only their consciences, and those of their fellow doctors, limit them.

Into this milieu rolled Christopher Duntsch, M.D., like a 100-year storm.

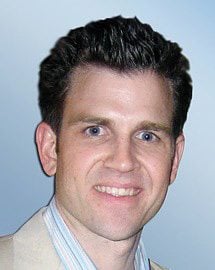

When he moved to Dallas in late 2010, Duntsch was 41 years old, fresh out of a residency program at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s Department of Neurosurgery in Memphis. In 2011, he founded a neurosurgery practice, Texas Neurosurgical Institute. He hired a marketing team and nurses. In November 2011 he was granted surgical privileges at Baylor Regional Medical Center of Plano. He put together a website and began bringing in patients.

Dr. Randall Kirby was another surgeon at Baylor Plano. In January 2012, he assisted on one of Duntsch’s surgeries. Kirby had spent 16 years performing general surgery in the Dallas area, in which time he’d assisted on more than 2,000 spine operations. Duntsch, he said, was the worst.

As they dressed for surgery, Duntsch boasted to Kirby that he was the best neurosurgeon in Dallas. “He felt,” Kirby wrote to the Texas Medical Board a year later, that “most of the spine surgery being done in Dallas was malpractice, and he was going to have to clean things up.”

The operation was a spinal fusion in which two vertebrae are joined; surgeons use a metal plate to help hold the vertebrae together. The procedure can improve stability in the back, according to the Mayo Clinic, and relieve pain. Among neurosurgeons, the procedure isn’t considered terribly difficult. Kirby said Duntsch had problems at nearly every step of the operation. He seemed to have a hard time moving organs and blood vessels out of the way, according to Kirby. He nicked the patient’s vertebral artery, causing the space he was working in to fill with blood. He then had trouble moving the plate into place.

“His performance,” Kirby wrote, “was pathetic . . . He was functioning at a first- or second-year neurosurgical resident level but had no apparent insight into how bad his technique was.”

After surgery, the patient, Barry Morguloff, woke up in more back pain than he’d started with and had no feeling in his left leg. For the next several months, he was in constant pain, according to Mike Lyons, his attorney. Scans later revealed bone fragments from Morguloff’s vertebrae lodged in the nerves of his back, according to Lyons.

Three weeks later, Duntsch performed a spinal fusion on Jerry Summers, a childhood friend. During the surgery, Duntsch sliced into one of the arteries running down Summers’ spine, causing massive bleeding, which he tried to staunch by packing coagulants around the wound. When Summers woke up he couldn’t move his arms or legs. Rather than immediately ordering scans to find out what was wrong, Duntsch moved on to other patients, according to Kirby’s letter to the Medical Board.

Baylor brought in a senior surgeon to fix the damage to Summers’ spine. His report was damning. He blamed Summers’ paralysis on Duntsch’s “surgical misadventures,” which had led to the artery being cut; the final straw, he wrote in his report, had been the packing of coagulants around the cut, which had seriously damaged Summers’ spinal cord. Topping it all off had been Duntsch’s failure to order tests and re-operate on Summers in a timely manner—a delay that likely cost his childhood friend the use of his arms and legs, according to the senior surgeon’s report. Summers remains paralyzed.

Following Summers’ surgery, Baylor Plano suspended Duntsch for 30 days—after that, he was supposed to be supervised on every surgery he performed, according to Kirby.

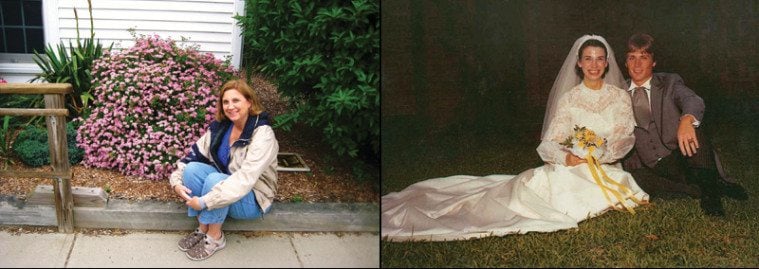

But Baylor didn’t hold him to that. Soon after Summers woke up paralyzed, a woman named Kellie Martin came to see Duntsch at Texas Neurosurgical Institute. She was 55 and had been experiencing persistent back pain after a fall at home. When physical therapy didn’t relieve the pain, her family doctor suggested she see a certain neurosurgeon—but the doctor couldn’t find that surgeon’s card, so she suggested Duntsch instead. She said Duntsch came highly recommended.

Kellie Martin and her husband, Don, went to see Duntsch, who suggested a procedure called a microlaminectomy, in which part of the spine is removed to relieve pressure on the nerves.

“He sounded impressive,” Don said. “He talked impressive. He was very eloquent in stating the causes and the need for the procedure. He felt confident. We felt confident too.”

Kellie Martin went into surgery on March 12, 2012. It was supposed to be a simple procedure, which is, perhaps, why Baylor didn’t put anyone in the operating room to supervise Duntsch. Don Martin, who was waiting outside, was told the operation wouldn’t take more than 45 minutes. Forty-five minutes passed, then an hour, two hours, with no word.

Don was a lieutenant with the Garland Police Department, and had spent enough time in hospitals to know this delay wasn’t a good sign. He went to the operating room and asked to speak to the doctor. When Duntsch came out, he told Don there had been “some complications,” and that Kellie would have to stay the night, but that the operation had gone fine.

Duntsch went back into the operating room and left Don waiting. He waited until they told him his wife had been sent to the intensive care unit. Then he waited for several more hours until the nurses came out to tell him and his daughters that Kellie Martin was dead.

The Collin County medical examiner who performed the autopsy was so astounded by what had happened to Kellie Martin’s body that he brought her back in for another examination. He listed the cause of death as “therapeutic misadventure,” according to his report. During surgery, Duntsch had sliced through one of the arteries alongside Martin’s spine, as he had with Summers. Unlike with Summers, though, he hadn’t noticed in time, and Martin bled to death, according to Texas Medical Board records.

Martin’s surgery was Duntsch’s last at Baylor. He resigned soon after, with full clinical privileges. By all appearances, he had simply decided to leave.

–

After his wife died, Don Martin found himself at a loss. “My whole world crashed,” he said. “I thought, this couldn’t have happened. It was supposed to be such a simple procedure. It was horrible. When I think about it, it’s just devastating.”

When I spoke to him, a year after his wife’s death, he told me that they had trusted Duntsch, and that there had been no sign suggesting they do otherwise. “Maybe,” he sighed, “we should have gotten a second opinion.”

But a second opinion wouldn’t have helped. Kellie Martin was in good health; a laminectomy is considered a minor procedure. There’s no reason to assume another doctor would have advised her differently. But no one bothered to tell the Martins—and there was no way for them to know—that their doctor had left a man paralyzed a month before in a case in which the hospital’s own surgeons found him at fault.

One might think that if a doctor had paralyzed one patient and had another die in the course of a month, it would be someone’s job to figure out why. But as in many other areas in Texas—benzene pollution from hydraulic fracturing sites; ammonium nitrate pileups at fertilizer plants—Martin’s death and Summers’ paralysis fell into a regulatory no man’s land. Once Duntsch left Baylor, he was no longer the hospital’s problem. The only entity that could stop Duntsch from seeing more patients was the Texas Medical Board.

But the board is limited in its ability to investigate malpractice. For one thing, it can open a case only if it receives a written complaint—akin to a police department that forbids its officers from investigating criminal activity they witness. With the exception of pain management clinics and anesthesiologists, the board doesn’t have the authority to inspect a doctor, or to start an investigation on its own.

During the summer of 2012, as Duntsch was searching for a new hospital, another doctor who had witnessed Duntsch’s errors at Baylor sent a complaint about Duntsch to the Medical Board, according to Kirby.

That complaint was filed—along with the 6,000 to 8,000 other complaints the Medical Board receives each year, in addition to the thousands of licensure applications the agency’s 156 employees must review. The process for resolving complaints is slow and painstaking, set up in statute to guarantee doctors the maximum legal protection. First, the Medical Board staff has to screen every complaint and has 45 days to decide whether the agency will act on it. If the board decides to act on a complaint—and only one in four complaints makes it that far—investigators begin subpoenaing hospital records, which the board will eventually send to a pair of volunteer doctors in the same specialty who will review the case (if they disagree, a third doctor has to be found to break the tie). These doctors are busy—they have practices of their own that pay a lot better than volunteering for the Medical Board—and there aren’t many of them. In a specialized field like neurosurgery, that means further months of delay.

Once the case has been put together, the investigators will make a recommendation to the board itself, a group of 12 physicians and seven laypeople appointed by the governor. They know if they try to discipline a doctor, the burden of proof will be on them. A poorly put-together case can mean months or years of expensive litigation. So the board members tend to act conservatively. They move slowly and only take action they’re reasonably sure will be effective. It takes the Texas Medical Board an average of nine months to resolve complaints. Some drag on for years.

And all the while, until their cases are resolved, doctors—even those accused of the most heinous malpractice—can continue to practice. Even the fact that the board is conducting an investigation remains confidential until the investigation is over. It’s left to hospitals to police their doctors.

In July 2012, four months after Kellie Martin’s death, Duntsch applied for surgical privileges at Dallas Medical Center. The hospital conducted an initial background check on Duntsch, and he came up clean. So while hospital administrators did a deeper background examination, they granted Duntsch temporary privileges.

It’s not clear how much Dallas Medical Center officials knew about Duntsch’s past or how much Baylor told them. Neither hospital would talk about Duntsch for this story. The answer, in both cases, seems to be very little. According to Baylor, Duntsch had clinical privileges when he resigned. As for what Baylor told Dallas Medical Center, a Baylor spokesperson said in a statement to the Observer that, “It has been the longstanding policy of Baylor to respond with comprehensive information when it receives a proper inquiry from another hospital. Because the credentialing process is deemed confidential under Texas Law, we are not permitted to discuss specific physicians or specific requests other than to say all policies were followed.”

Dallas Medical Center also declined to comment, citing privacy concerns. But according to Dr. Robert Henderson, another neurosurgeon at Dallas Medical Center, the “comprehensive information” Baylor sent over when Duntsch applied consisted of an email saying that there were no issues with Duntsch’s performance, that he’d been on staff and had voluntarily resigned.

Henderson says that Duntsch told the Dallas Medical Center administration about the Martin and Summers cases, but explained that the outcomes hadn’t been his fault: Summers, he said, had been paralyzed by a bad drug interaction, and Martin had died because of complications from anesthesia. He didn’t tell them about Baylor’s internal reports that faulted him in both cases, according to Henderson. Duntsch’s explanation, along with the email from Baylor, was enough to get him a trial run of five surgeries at Dallas Medical Center.

“I think their rationale was, he’s a trained neurosurgeon, a combined M.D.-Ph.D.,” Henderson said. “How much risk can there be?”

The first three surgeries of Duntsch’s trial took place on three consecutive days in July 2012, a month after the first complaint against him with the Texas Medical Board. The first surgery went fine. In the second, while doing a cervical fusion on a woman named Floella Brown, Duntsch “removed a bone from an area that was not required by any clinical or anatomical standards, resulting in injury to the vertebral artery,” according to Texas Medical Board records. Brown was later found unresponsive in her hospital room and staff couldn’t contact Duntsch for 90 minutes, according to those records. Brown had suffered excessive blood loss and a stroke, according to the agency. By the time she was transferred to UT Southwestern Medical Center later that day, she was brain dead. As she lay dying, Duntsch performed his third surgery, on a woman named Mary Efurd. Another spinal fusion; another routine procedure. Efurd woke up after surgery in horrible pain, barely able to move her legs.

Two days later, once Efurd was stable, Henderson was assigned to do the repair surgery. A CT scan found that the metal spinal fusion hardware, meant to be placed on the patient’s spine to keep the vertebrae from moving, was sunk into the muscles of her lower back, inches from her spine.

Henderson went in to remove it. He had been a neurosurgeon for 40 years and what he saw inside Efurd’s back shocked him.

“He had amputated a nerve root,” Henderson said. “It was just gone. And in its place is where he had placed the fusion. He’d made multiple screw holes on the left everywhere but where he had needed to be. On the right side, there was a screw through a portion of the S1 nerve root.”

At first, Henderson thought Duntsch might be an impostor. He faxed over a picture of Duntsch to the residency program at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center to see if Duntsch had graduated.

“I couldn’t believe a trained surgeon could do this,” Henderson told me. “He just had no recognition of the proper anatomy. He had no idea what he was doing. At every step of the way, you would have to know the right thing to do so you could do the wrong thing, because he did all the wrong things.”

But the school told Henderson that Duntsch had completed the residency program. He was horrified to realize that Duntsch was going to keep practicing. After a few calls to various Dallas-area medical societies, someone suggested he call the Medical Board.

“So I called them up, and they said, ‘Will you fill out a complaint, and we’ll probably read the complaint in about 30 days, and we’ll start an investigation after that.’

“I said, ‘You don’t seem to understand. This guy already killed somebody, made another a quad, made a partial paraplegic out of my patient.’ I said, ‘He needs to be stopped. Not only shouldn’t he be operating, he shouldn’t be making any decisions about treatment or pathology.’ It had no effect whatsoever.”

–

After the Brown and Efurd debacles in July 2012, the CEO of Dallas Medical Center, Dr. Corazon Hernandez, fired Duntsch and reported him to the Medical Board, according to Henderson.

Over the next year, the Medical Board would receive at least six more complaints from doctors who had seen Duntsch’s work up close. Doctors, and then, later, lawyers would call the board’s investigators and sometimes even the board members themselves, begging them to do something. They all received the same response Henderson had: Send us what you have, and we’ll get back to you.

We now know that the Texas Medical Board was working behind the scenes in summer 2012, trying to find grounds to temporarily suspend Duntsch’s license. The temporary suspension was a power the Legislature gave the board in 2003. For the first time, the board could suspend without a hearing doctors who “constituted a continuing threat to the public welfare,” i.e., cases where the public couldn’t afford to wait for the full board proceedings. For a temporary suspension, the standard is even higher than the board’s other enforcement actions. It isn’t enough to prove that a doctor did something awful. To suspend a license, as one Medical Board staffer explained, there has to be enough evidence to prove a pattern.

And while the Medical Board investigated, the pattern continued. If you were a patient in the Dallas area around this time looking for a spine surgeon, there would have been nothing to suggest that Duntsch was a risky choice. Because investigations are confidential, Duntsch’s public record with the Texas Medical Board remained clean. On the online doctor-rating site Healthgrades.com, he had 4.5 stars out of five. He had a slick marketing team in Best Docs Network, a physician PR company that pumps out infomercials to local TV stations. In one, Duntsch tells the story, over stock footage of an operation, of a taxing back surgery he performed on an older woman. The surgery, he said, beaming into the camera, was a resounding success. “And the only thing she complained about was she couldn’t find what she wanted to watch on TV.”

Meanwhile, he was continuing to get patients, continuing to operate. In December 2012, he performed a cervical fusion at Legacy Surgery Center of Frisco that left his patient with paralyzed vocal cords—an unheard-of complication. In January, one of his patients at University General Hospital Dallas woke up paralyzed from the waist down, according to the patient’s lawyer.

None of this hurt his career. At the end of May 2013, Kirby and Henderson received invitations to a celebratory dinner, courtesy of University General Hospital, to meet their new neurosurgeon, Dr. Christopher Duntsch, at an expensive uptown restaurant.

Kirby called the owner of University General. “I called them and said, ‘He’s bad news, multiple members have reported him to the Med Board.’”

According to Kirby, the hospital owner told him that Duntsch had privileges to do only minimally invasive surgeries.

It was a minimally invasive surgery, Kirby said, that killed Kellie Martin.

Two weeks later, on June 14, 2013, Kirby got a call to come to University General to do a recovery surgery on one of Duntsch’s patients. The surgery had gone so badly, Kirby later wrote to the Medical Board, that the rest of the OR team had to physically restrain Duntsch from continuing. For two days the patient, Jeffrey Glidewell, lay unattended in the ICU while Duntsch made excuses to the family. Finally the family fired him. When Kirby saw Glidewell, he later wrote the Medical Board, he was “horrified.” The incision, he wrote, was cut into Glidewell’s throat “two or three inches lower and an inch midline from where it should have been oriented … saliva and pus were coming out of the wound.”

Duntsch, it turned out, had, as with other patients, cut into Glidewell’s vertebral artery; an MRI found that he had also left a sponge festering in the soft tissue of Glidewell’s throat.

Later in June 2013 Kirby sent a sworn statement to the Medical Board in which he laid out all of Duntsch’s patients he knew about and included reports from many of the surgeons who had worked on them. Near the end of his report, Kirby wrote, “The [Medical Board] must stop this sociopath Duntsch immediately or he will continue [to] maim and kill innocent patients.” Perhaps it was the completeness and forcefulness of his presentation, perhaps it was the fact that another neurosurgeon had just joined the board, and he understood as none of the rest did the severity of what Duntsch had done. Whatever the reason, this time the board acted. On June 26, the board held an emergency meeting and suspended Duntsch’s license.

More than a year had passed since Kellie Martin’s death and the complaint that started it all. In the time between the first complaint to the board, and when Duntsch was finally stopped on June 26, five of his patients were seriously injured and one died.

Until the day of the suspension, if you had looked Duntsch up on the Texas Medical Board website, you would have found him a physician in good standing.

–

After his license was suspended, Duntsch disappeared. At his home and office, my calls rang and rang before going to voicemail boxes that were full. It’s not clear how such a well-trained surgeon could have performed so disastrously, but the June 26 Medical Board report offers a hint: “Respondent is unable to practice medicine with reasonable skill and safety due to impairment from drugs or alcohol.”

Duntsch’s license is currently on temporary suspension pending further action by the board. In the aftermath of the debacle, the doctors who saw Duntsch’s handiwork were left to make sense of what happened.

Kirby, the surgeon from Baylor, was philosophical. “This is a once-in-a-generation occurrence, that we have someone off the rails this bad—this is why no one saw this coming.”

Most of the doctors on the Medical Board, he pointed out, aren’t surgeons. “They just can’t comprehend that an M.D.-Ph.D. neurosurgeon could do what Christopher Duntsch was doing. Like pilot training—you don’t expect a trained pilot to get drunk and fly his plane into the ground.”

But it’s more complicated than that. Duntsch was an anomaly, one of the worst malpractice cases Texas has seen in decades. (So far only Mary Efurd and the family of Floella Brown have filed suit against Duntsch, though the other patients or their families have all retained counsel as well.)

But Duntsch was an anomaly for another reason: the barrage of complaints to the board. This was a very rare phenomenon—most of the doctors who reported Duntsch had never filed a report before. Duntsch’s case raises the question: If it took a year to stop a doctor accused of this much, what else is getting through?

In 2012, the public interest research group Public Citizen commissioned a research project to cross-reference doctors sanctioned by the Texas Medical Board with those listed in the National Practitioner Databank, managed by the federal Department of Health and Human Services. Every time a doctor loses clinical privileges at a hospital, or has them suspended, hospitals are required by law to notify the National Practitioner Databank. Public Citizen found that 793 Texas doctors had lost clinical privileges between 1990 and 2011.

Many of them had committed serious practice violations. Their fellow physicians had found them committing such offenses as malpractice, sexual assault and drug use.

But Public Citizen found that of those 793 doctors, the Texas Medical Board had taken serious action in less than half the cases.

Among these doctors who escaped Medical Board action was one who racked up 22 malpractice suits over 12 years, totaling $2.4 million in judgments, for such things as performing unnecessary or harmful procedures or, in one case, removing the wrong body part, according to the federal database. Though the Texas Medical Board is required by statute to investigate any doctor with more than three malpractice suits, no action was ever taken against the doctor by the state. (And the National Practitioner Databank doesn’t make doctors’ names public, so we don’t know who they are.) Though a hospital peer review took this doctor’s privileges in 2006, he continued to practice for three more years until he retired, according to federal records.

Another had 13 civil judgments against him, including for wrongful death, permanent injury and two cases of removing the wrong body part. In this case, as well, the Texas Medical Board took no action, according to Public Citizen.

Even when the board does sanction a doctor, those sanctions are often light—even in cases in which the doctor is badly impaired. In 1998, the board found Dr. Greggory Phillips to be addicted to painkillers, and that he was prescribing painkillers to himself and family members. The board suspended his license but then immediately stayed the suspension and gave him probation. In 2007, he was found to be leaving presigned prescription pads with his nurse so she could prescribe controlled substances while he was away, according to Public Citizen. In 2008 one of his patients died of a prescription drug overdose after he had prescribed her a lethal dose of the painkiller Tramadol. The patient’s mother complained to the Medical Board. While that complaint worked its way through the system, another of his patients died of a hydrocodone overdose. The board, when it finally handed down an order in 2011, faulted him for both deaths. The board fined him $3,000, assigned him a monitor, and required him to take classes in medical recordkeeping. In February 2013, for unclear reasons, the board took his license.

And then there was the 2011 case of Dr. Rolando Arafiles, the West Texas doctor who sicced the county sheriff on two nurses who dared report him to the Texas Medical Board (see “Intent to Harm,” March 2011). Before moving to West Texas, Arafiles had run a small alternative clinic in Victoria, peddling chelation therapy, a fringe cure that is supposed to rid the body of heavy metals. One patient had a stroke following a chelation therapy. A Medical Board investigation later found that Arafiles’ assistant was inappropriately prescribing stimulants and diuretics to patients. The board forbade Arafiles to supervise nurses or physician assistants anymore. But a few years later, he popped up in Kermit doing just that—as well as selling drugs out of the operating room and performing bizarre surgeries he hadn’t been trained for. In June 2010, following the media circus around the prosecution of the Kermit nurses, they filed a complaint against him. Yet Arafiles didn’t surrender his license until November 2011, after he had been convicted of a felony.

These doctors are anomalies too. The point isn’t that all doctors are dangerous, or even that any more than a tiny minority are. But in Texas, when you go to see a doctor, there is a small but real chance that the doctor has been found by his or her peers to be a danger to the public, and that no one has bothered to do anything about it yet. That as you walk into the waiting room of a Christopher Duntsch or Greggory Phillips or Rolando Arafiles, somewhere, in some office in Austin, the parties the state has deemed responsible are sitting at desks quietly investigating.

–

At one point Dr. Henderson sent me a tape of a conversation he had with the main Medical Board investigator assigned to Duntsch’s case. The conversation took place in January 2013, after it had become clear that Duntsch would practice until someone stopped him, six months before anyone actually did. On the tape, Henderson demands to know why Duntsch is still practicing.

The investigator, Maria Lopez, lets him yell. When she responds, she’s quiet.

“Sometimes we know that someone’s bad, but when it comes to taking them to a hearing and proving it to where we can actually do some disciplinary action, it takes time of gathering evidence. … Unfortunately, sometimes it takes longer than we want.”

What Henderson took from this, he told me, is that “we’re dealing with people who don’t do the job they are hired to do.”

But it’s more complicated than that. Before we ask if the board does its job, we have to ask what is the job the Legislature assigned to the board, and what resources the board gets to do that job.

Texas’ number of license applications has grown every year since 2003, when medical malpractice damage caps passed. Every year the board is both overseeing many more doctors and bringing in more money. But it doesn’t get to keep much of it: In fiscal year 2013, the board sent almost $40 million to the state’s General Revenue fund, of which it got about $11 million back. (Like other state licensing agencies—the Pharmacy Board, the Nurse Practitioner Board—the Medical Board operates at a surplus for the state.)

Public Citizen concluded that the board moves slowly because it’s understaffed and underfunded. But when I talked to Medical Board spokesperson Megan Goode about this, she said Public Citizen had it wrong—that the board isn’t underfunded at all. Things were rough during the state budget crisis in 2011, but now hiring is back up to normal.

The problem, she said, isn’t staff. In an official statement, she wrote, “The way the law is currently written, with a high bar of evidence for the board to meet, the process can take time so that the board can build a solid case. It would clearly be a policy decision for the Legislature to consider whether the process or the standards for evidence required for a temporary suspension need to change.”

Leigh Hopper, formerly the Medical Board spokesperson, put it more bluntly. “You could have a Medical Board that’s the size of the [Texas Department of Public Safety],” she said, “but the state doesn’t want that. It’s more or less satisfied with the way that things work.”

We have to consider the uncomfortable possibility that Christopher Duntsch is to the medical system what the recent West explosion was to the fertilizer industry—a regrettable tragedy, but the price of living in a free-market system. And that with Duntsch, as with other bad doctors, the system worked exactly as it was designed to.

Editor’s note: For more information about Dr. Christopher Duntsch’s case, listen to the 2018 podcast “Dr. Death.”