The Serendipity Wrangler

Bill Wittliff and the Southwestern Writers Collection

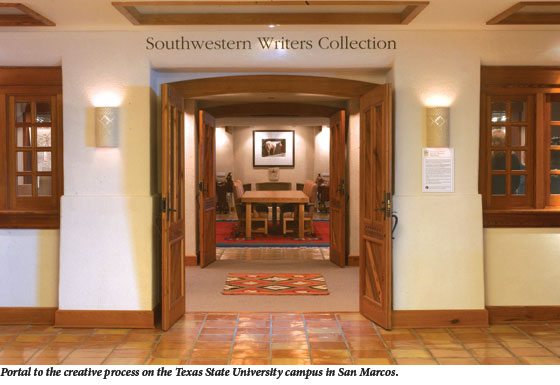

The Southwestern Writers Collection is located on the top floor of the Alkek Library on the Texas State University campus in San Marcos. White walls, wooden doors, Saltillo tile floors and Indian rugs give its exhibit halls and conference rooms the feel of an adobe church. The collection’s archive houses the papers and artifacts of regional writers, filmmakers, musicians, and photographers. Robert Duvall’s Lonesome Dove costumes and Willie Nelson song lyrics jotted on restaurant napkins are among the treasures in its temperature-controlled vault, as are the collection’s newest gems: Cormac McCarthy’s manuscripts and working papers. At the entrance stands political cartoonist Pat Oliphant’s larger-than-life, full-body bronze sculpture of Glen Rose writer John Graves. The piece was commissioned by collection co-founders Bill and Sally Wittliff, and Bill took the photo on which the sculpture is based.

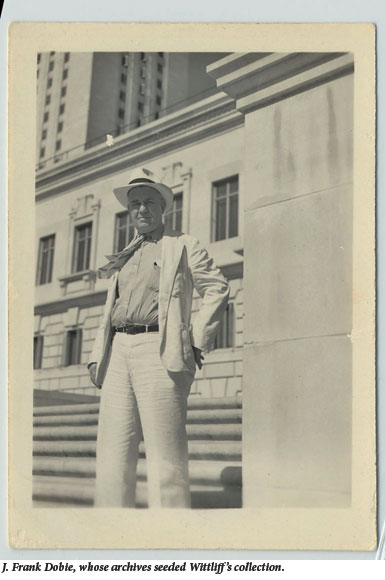

“The collection was set up so writers could be seen as human beings, not as stick figures,” Wittliff says. “J. Frank Dobie’s collection is what essentially started it. We’ve got his pipes, his Stetson, his funny shoes. We’ve got his white suit. We’ve got his typewriter. We’ve got his fountain pen that he used to write the morning he died. But all of those things, I think, add up to an image of the full guy.”

Wittliff’s Austin office is a microcosm of the Texas State collection itself. One of John Graves’ paddles from his Goodbye to a River canoe trip hangs on the wall. Crammed bookshelves jostle with soon-to-be-hung paintings for floor space. Wittliff’s black standard poodle and his assistant Amanda’s labrador navigate piles of photographs, manuscripts, and letters.

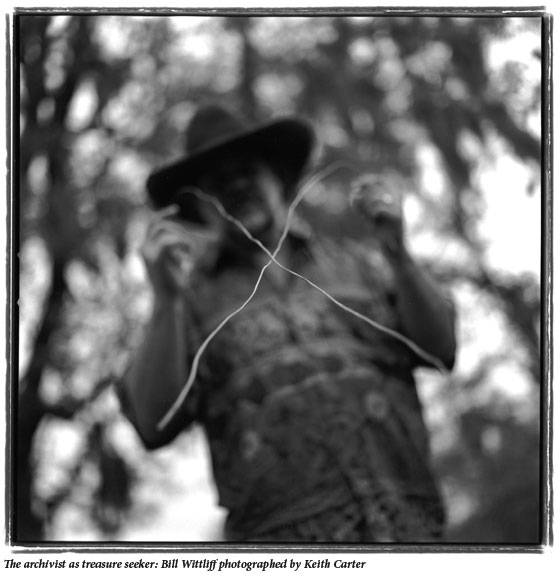

“There’s all kinds of stuff,” Wittliff says, rummaging in a corner. “My mother said I was a ‘pilot.’ I’d pile it here and then I’d pile it over there.”Abandoning a search for some hidden treasure, Wittliff sits behind his desk and smiles. With his gray hair, beard, and a button-down shirt emblazoned with Royal Wulff fishing flies, his appearance is as august and unkempt as his office.

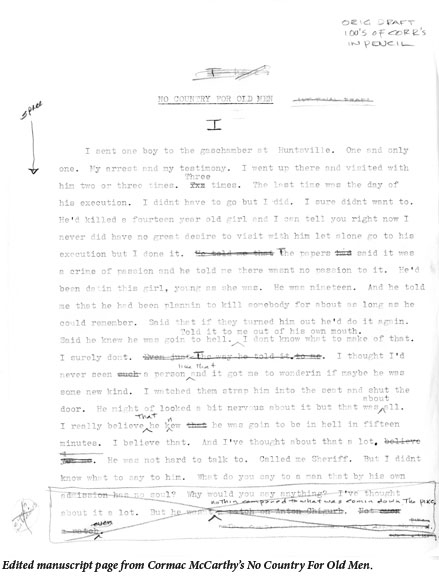

“On one hand, the collection is a place of preservation,” Wittliff says. “But on the other hand, it’s a place of inspiration. Young writers or people with the itch to write can come in and see that all these guys are just folks who have the urge to create and to work their asses off at it. I absolutely know that if I had gone into a place like that when I was 16 or 17 or 18 and seen John’s manuscript or McMurtry’s or Cormac’s or whatever, and seen them scratched out and struggling to find just the right word, just the right sentence to express their thoughts, I’d have said, ‘Well, shit. These guys are working. I mean, I can do that.'”

As a child who was frequently moved around Central Texas, Wittliff sought out front-porch storytellers. “It was a way of belonging,” Wittliff remembers. “I wanted to belong.”

A love of books was a natural progression.

“Bill had always been interested in books, but not had access to very many of them,” Sally says of her husband. “His mother married a guy who was a retiring cowboy. They moved to Blanco. He had some books. One of them was a Dobie book. Bill picked it up and discovered a story between those hard covers that his grandfather had told him. He said that lightbulbs went off in his head. That was the first time he realized that the stuff of his place and his life might be worthy of being on pages.”

Wittliff earned an advertising degree from the University of Texas and then decided that wasn’t the world for him. After a stint at Southern Methodist University Press in Dallas, he returned to Austin, where he and Sally founded Encino Press in 1964, publishing Southwestern writers and subjects.

“Starting the Encino Press was a way of being involved with books without being at risk personally,” Wittliff says. “Later, when I got more confident, I was willing to take my clothes off and lay down on the table. Which is what it is when you’re writing and really going for it.”

Though Encino Press was successful, Wittliff eventually wanted a change in career.

“We started the press when we were just children, really,” Wittliff says. “Right out of school. It was a little mom-and-pop organization. It was great fun, and it worked. We were actually making a living. Basically, one day I was sitting there and I thought, ‘Well, today is just like yesterday. And tomorrow’s going to be like today, too.’ And then I thought, ‘Jesus, this is stagnant.'”

In 1969, Wittliff traveled to Mexico and photographed vaqueros working in the traditional ways. His pictures eventually added up to a traveling exhibit and book entitled Vaquero. He wrote a screenplay called Thaddeus Rose and Eddie, which was made into a CBS movie starring Johnny Cash. Francis Ford Coppola hired Wittliff to work on the script for The Black Stallion, cementing his career in the industry. Over the years, his screen credits have included Raggedy Man, Lonesome Dove, Legends of the Fall, and The Perfect Storm.

Because Encino Press had specialized in regional material about Texas and the Southwest, the Wittliffs got to know almost everybody in local literary circles, and those friendships played a supporting role in the genesis of the Southwestern Writers Collection.

“We had the relationships with the people,” Sally says. “There’s a certain amount of arrogance in being a writer. They don’t want to think of their archives as going into the garbage heap when they’re gone.”

Writers Collection curator Connie Todd recalls that J. Frank Dobie’s secretary inherited the writer’s house and its contents. The day before she began selling off the contents, in 1985, she called Wittliff.

“Because of Bill’s publishing house and screenwriting, the Texas literary scene knew him and trusted him,” Todd says. “So he was sitting at Dobie’s desk, writing a check for it, when he looked over in the corner and saw a pile of boxes. The secretary said they were the last of Doctor D’s writing archives.”

They were going to be sold, she said, so Wittliff looked them over. “How much for everything?” Wittliff asked.

Wittliff called his wife to make sure the check would clear and then walked away with boxes of Dobie’s manuscripts. The sale was over.

“I was working for [Wittliff] at the time,” Todd says. “As we unloaded the boxes and piled them on the Encino Press’s floor, Bill began to realize that it was time to start a collection of some kind. He wanted to focus on Texas and Southwestern writers.”

Dobie, Wittliff says, made the case that Texas was a valid subject for writers as long as they weren’t provincial. “There was a moment in time when that was an unusual thing to recognize,” he says. “He saw how it fit with other things in the world.”

Wittliff had spoken to Texas State classes about screenwriting, so he approached the school about putting Dobie’s papers there. He also offered to explore more acquisitions if Texas State offered some space and a curator. “That was when it all started,” she says, “almost 22 years ago.”

From its earliest days, the Southwestern Writers Collection has been a story of serendipity, which is to say a story of Wittliff’s ability to see, and to make, connections.

“I think the great secret of the universe is in this sentence: Whatever you’re looking for is looking for you too,” Wittliff says. “Once we started this collection, as goofy as it sounds, stuff started walking through the door, showing itself one place or other.”

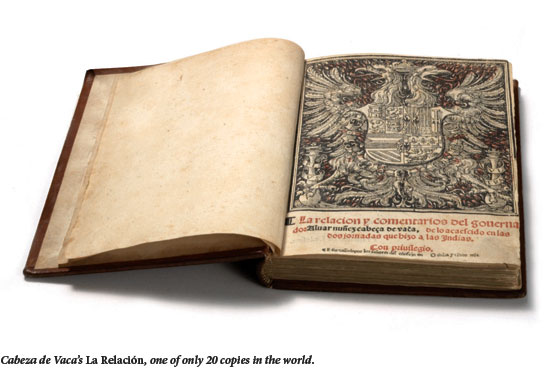

Within a year of the collection’s founding in 1986, a copy of Cabeza de Vaca’s La Relación turned up for sale just a few miles from Wittliff’s office. The 1555 edition, one of 20 copies in the world, recounts the Spanish conquistador’s shipwreck on Galveston Island, subsequent enslavement by Indians, and eventual liberty. It is the first written account of the American Southwest.

“I’m told that there’s another one for sale now from Buenos Aires or somewhere down in South America that’s a million dollars,” Wittliff says. (He declines to specify the price paid for the collection’s copy).”But I didn’t think another one would turn up in my lifetime.”

The Wittliffs and an anonymous friend bought the book and donated it to the collection.

“La Relación became a catalyst,” Todd says. “Immediately there was research done. We digitized it and put it up on the Web site (http://alkek.library.txstate.edu/swwc/cdv/) so that everybody in the world could see it. That was wonderful for scholars who were studying text.”The collection also began attracting film artifacts through Wittliff’s screenwriting work. Friends like Tommy Lee Jones and Sam Shepard periodically dropped by the campus to drop off boxes of material.

“We have countless hours of conversation on tape between Sam and Bob Dylan,” Wittliff says. “Unproduced plays. A lot of stuff like that.”

Then there’s Candy Barr, a world-famous stripper originally from Edna, Texas. In 1951, at age 16, she starred in one of the world’s first pornographic movies. Later in life, she was involved with gangster Micky Cohen and Jack Ruby. Barr, whose real name was Juanita Slusher, also happened to have gone to grammar school with Wittliff.

“One day, a lady walked in here and said she was a friend of Candy Barr,” Wittliff says. “She was selling Candy’s stripping costumes for her. In addition to the costumes, she had this 400-page interview with Candy Barr about her whole life. It is utterly fascinating. All of that stuff is now in the collection, including the interview, which is restricted. Nobody can read it.”

Barr wanted it that way. Though there was talk of a biography or screenplay, she decided not to make the material public. “I’ve read it all,” Wittliff says, “and it is enormously powerful human stuff. It’s just amazing.” Wittliff has yet to begin negotiating with Barr’s family to provide potential future access.

In 1996, the Wittliffs started collecting photography.

“One of the great collections of the world, of course, is at the Humanities Research Center in the University of Texas,” Wittliff says. “But it’s not Southwestern. It’s more of a world-reaching collection. I was sitting right here one day, and the idea whipped by that it’d be cool to do a collection of Southwestern and Mexican photography.”

Working on a small budget, Wittliff and Todd began purchasing works from artists they liked. Todd showed Wittliff a photo by Mexican artist Mariana Yampolsky in an Austin gallery. Wittliff liked it and told Todd to check the artist out during a vacation in Mexico City. Todd couldn’t find her in the hotel’s directories.

The following morning, she ran into a curator friend from El Paso and told him she was looking for Yampolsky. “He said, ‘Oh, Mariana. Just a second. I have her number in my billfold,'” Todd recalls. “Bill is a great believer in serendipity. When I told him that story, he said, ‘OK, we’re going with her.'”

The photography collection now includes original prints by Yampolsky, Graciela Iturbide, Keith Carter, and Rocky Schenck.

“I was aware of Rocky’s work,” Wittliff says. “Then one day he had a bunch of pictures in a magazine, and they had a little bio that said ‘originally from Dripping Springs, Texas. Now lives in Los Angeles.’ So I called information and got a sweet operator who tracked the number down in Santa Monica.”

Wittliff, originally from Blanco just down the road from Dripping Springs, called Schenck. “‘You don’t know me,” Wittliff recalls saying. “‘My name’s Billy Wittliff, and originally I’m from Blanco. In 1957, we whipped your ass in football.'”

Wittliff recalls that Schenck replied, “Well, you didn’t whip my ass because they wouldn’t let me play.” Wittliff said he was trying to build a world-class photo collection on the cheap. “He said, ‘How cheap?’ I told him, and he said, ‘Whoa!'”

Tom Staley directs UT’s world-class Ransom Humanities Research Center, which also collects manuscripts and papers. He knows whereof Wittliff speaks.

“Writing is an art and a craft, and it’s not sudden inspiration. When you learn to study the false starts, when you learn to study the changes, the corrections, you begin to see the writer’s struggle. It’s the trajectory of the artist’s imagination,” he says. “The book is the end of it. The manuscripts are the live, living process of it.”

Though Staley and Wittliff are both in the archives game, they play on different fields. The Ransom collection spans the globe, while the Texas State collection concentrates on regional artists. UT buys its archives with cash drawn from oil coffers and one of the nation’s largest alumni bases. Most of Texas State’s literary holdings have been donated. Its photographic archives have been compiled at discount prices.

“We don’t really collect Texas writers as such,” Staley says. “We’re just in a different area.”

One Texas-linked writer the Ransom Center had been interested in was Pulitzer Prize-winning author Cormac McCarthy, but in January 2008, McCarthy decided to entrust his manuscripts, correspondence, and unpublished screenplays with Wittliff at Texas State.

If the competition bruised any egos, there’s no sign of it. “We know each other,” Staley says of the archivist community at large. “Book dealers and manuscript people have to understand that. We do talk with each other. In most cases, we’re friends. I’m glad we have McCarthy’s archive here in Texas. And so close.”

While the Texas State collection’s archives have long held regional interest, the McCarthy papers will bring a new level of international attention. The deal was made possible by a two-decade friendship between Wittliff and McCarthy, and by Wittliff’s eye for spotting talent early.

Wittliff first came across McCarthy in the 1980s while serving on the executive board of trustees for Robert Redford’s Sundance Institute.

“Somebody sent in a script that Cormac had written,” Wittliff recounts. “The screenplay was Cities of the Plain. It started as a film script before becoming a book. I read it and was absolutely blown away by the language. I had never heard of him at that point. I tracked him down and essentially wrote him what was a fan letter. I just said how much I admired his writing and so on. We exchanged a few letters and then later met. It was kind of casual.”

When the deal was finalized earlier this year, Todd flew to Santa Fe along with several collection employees. They rented two U-Haul vans and drove to McCarthy’s home in the hills. After coffee with the author, they loaded his archives into the vans and drove straight back to Texas.

McCarthy’s archiv

s were neatly arranged in plastic bins, Todd says. Writers Collection archivist Katie Salzmann

is now preparing the material for public viewing.

“We’re doing a lot of housing, making sure that everything will be physically secure,” Salzmann says. “Also, intellectually, we want to make a real detailed inventory of everything. We’re even checking the page numbers and making sure that all the papers are complete. We’re coming up with a full description of each item within the collection.”

Salzmann rolls out a dolly loaded with boxes, opens one, and lays out a typescript marked with comments. Some are in green or red ink, others in pencil, the handwriting small and meticulous.

“This is the typescript for Cormac’s first novel, The Orchard Keeper,” Todd says. “These are his pencil corrections and annotations. He studied architecture early on, and his handwriting is very, very neat.”

The book’s tentative titles included The Workers at the Kiln, Toilers at the Kiln and Watchglass and Fiddle, and maybe Hourglass and Fiddle.

“The red ink is the copyeditor,” Todd says of a second draft of McCarthy’s 2006 novel, The Road. Although worked over, it has fewer notes than The Orchard Keeper.

“They’re talking about a little lamp which he calls a ‘slutlamp’. ‘Slut’ being the term for a kind of oil, kind of a thick oil. [The copy editor] says, ‘Okay, I can find only slutlight’. Cormac responds, ‘OED just calls it a slut’. OED is the Oxford English Dictionary. Here’s another page she’s circled. She says, ‘Okay, the only spelling I can find for this is with an ‘I’. He crossed that out and then wrote, ‘See OED’.”

Todd laughs.

“She just looked in the wrong dictionary!”

It’s getting late in the afternoon. Salzmann carefully reboxes McCarthy’s manuscripts and loads them back onto the dolly. One of the dolly wheels squeaks in a syncopated rhythm as she wheels the boxes across the room. Todd watches after her.

“I think collecting archives is an optimistic profession,” Todd says. “It presupposes that there will be people in a hundred years who will want to read this stuff. Who knows if we made the right choices?”

That’s the sort of question that could paralyze a writer, never mind an archivist, but for Wittliff the process may be more important than any particular result.

“I tried really to never think too much, but rather just to respond intuitively,” Wittliff says. “It’s like the Dobie stuff. It felt right to say, ‘How much for this stuff?’ Then it felt right to say, ‘Hey, we ought to try to start a Southwestern writers collection somewhere.’ This felt right. That felt right. That didn’t feel right. And just act on that. I generally get in a lot of trouble when I think.”

Stayton Bonner is a writer living in Austin