What the Fifth is Taking

Carla Main gives the notion of eminent domain a personality and a persona, bringing humanity and a slap-you-into-reality perspective to the political debate over the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution-and the power it gives the government to take what’s yours-by profiling one family’s tangle with a local government intent on taking its land.

Within the narrative, Main relentlessly hawks her mantra, which slants politically conservative: “Eminent domain bad; private property rights good.” Her telling of one family’s experience shows how easy it is for the government to appropriate private land through its constitutionally given police power, and shows what can happen when one family fights back.

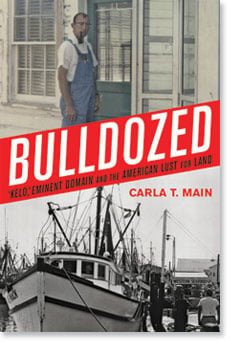

Bulldozed offers the nitty-gritty and brackish details behind a lawsuit, Western Seafood v. City of Freeport, Texas, that personifies eminent domain, Texas-style. The tale begins in 2002, when the city of Freeport teamed up with a private developer on plans to build a private marina on the Old Brazos River channel. In the way stood the Gore family, which ran a shrimping business on the land needed for the development. After the Gores refused to sell at a lowball price, the city resorted to eminent domain to take it. More than three years later, neither side would be completely satisfied with a court ruling that let the Gores keep their land, sort of.

Historically, Main recounts, governments primarily relied on eminent domain to take private land for public use-schools, roads, hospitals-things for the common betterment and benefit of all. Common sense was the standard applied to taking private land under the Fifth Amendment, which says that private property won’t be taken for public use without just compensation.

Of late, Main argues, eminent domain has become the method du jour by which government facilitates-and often forces-transfers of property from one private party to another, not to help citizens, but to enrich government coffers. This more-sinister use of state power is a developer’s darling deal, with a kickback-legal of course-for the government entity that orchestrated the operation.

Elected officials regularly use eminent domain as a pretense to create facades-pretty, planned communities-and to raise money. As Main writes, “[P]lanning consultants are far too polite and well trained to come right out and say what a city needs is fewer poor people and more people with a lot of money to spend.” Hence, the prevailing formula for implementing eminent domain. Bellow “blight.” Bid “adios” to the lower class. Seduce the wealthy with buzz phrases like “urban renewal” and “revitalization.” Watch the cash come. It’s a multitiered process for generating municipal revenue.

To demonstrate, Main uses the Gore family and its legal fight-which at times seems more akin to a barroom brawl. The Gores wanted to keep their waterfront land and keep running the Western Seafood business there.

One moment, they were running a business on land that had been in the family for three generations, paying taxes, contributing to the community. The next, they found themselves trying to fend off a city council that had solicited a commercial developer to build a marina on their property.

Main asks, and the Gores tell, how the American dream becomes a dystopia.

When faced with eminent domain, the Gores had a choice, attack or acquiesce. After failed attempts to negotiate with the city and developer Hiram Walker Royall of Dallas, a descendent of the founder of Humble Oil, the Gores waded into the fight, taking the offensive by filing a countersuit against the city’s eminent domain proceeding.

Main focuses extensively on the protagonists of this drama. The clan’s patriarch, Wright Winston “Pappy” Gore, was a self-reliant, self-made man who founded Western Seafood and made it a success. Growing up during the Depression, Pappy owned two pairs of overalls, one for weekdays and one for Sunday church. He lived in the fish house-“a wooden structure that abutted the pier and wasn’t meant to be lived in”-at river’s edge while building his business. As his family grew, he bought a trailer and parked it on the property. Running the business was life for Pappy and all the Gores.

At 86, Pappy lay on his deathbed in a comfortable suburban home, unable or unwilling to succumb to death until he knew whether a court judgment would secure his family’s property rights.

Isabel, the Gore matriarch, birthed babies, cleaned the docks, and deheaded shrimp, the quintessential multitasking woman. She was sufficiently no-nonsensical to manage a business and simultaneously nurture the Vietnamese trawlers who worked the river. They called her “Mama.”

Isabel was life companion and business partner to Pappy, and later, a community leader. The local Chamber of Commerce named her Woman of the Year. Main repetitively mentions this award, as if to build some credibility for the Gores, to show that they were neither Freeport newcomers nor kooks hindering “progress” for personal gain. The Gores were just regular folks, except that they owned 330 feet of riverfront, land perfect for a private marina.

Wright Jr. and Beth Gore, son and daughter-in-law to Pappy and Isabel, play a part in the story, but their son Wright III is the hero, the force behind the lawsuit.

The reader sees the story from Wright III’s point of view. He’s part reactionary, gallantly dueling the city council, but mostly an unwitting and sympathetic, regular guy trying to save his family’s land.

Though Main doesn’t bill Bulldozed as a mere recounting of Gore family and business history, she often digresses into their near-beatification. The veneration blends with, and perhaps stems from, Main’s black-and-white political worldview. If the Gores are heroes, there must be an antagonist with allies as a counterweight. The case of Western Seafood becomes personal; it’s Wright III v. H. Walker Royall, man against man, not plaintiff versus defendant.

At times Main imposes an element of personal morality on eminent domain and the Gore’s legal battle. The unintended effect is that people appear more as characters in a work of fiction, superficial, nearly unreal, as they grapple with the case’s issues.

If the small-town residents of Freeport are good, then the residents of nearby Lake Jackson are less so. Big-city dwellers, like the evil-intentioned land-stealer Royall of Dallas, are bad. Hard-earned, modest wealth is OK, but inherited wealth, not so much, or maybe not at all. There’s an inherent nobility in being working class, and more so for being poor. Open heaven’s portals for those living paycheck to paycheck, like many of Freeport’s citizens.

Main works hard-too hard perhaps-at this characterization, describing in exhausting detail the family pedigree and Royall’s lifestyle-money, museums, and a Mercedes in his garage in the ritzy Turtle Creek Dallas neighborhood. Conversely, describing Pappy, she notes that “a boy whose daddy labored in the oilfield has just as much right to dream as a boy whose daddy owned those oilfields.”

Dissent and civil disobedience are noble if the aim is saving your family’s land and business. Law-abiding, though, is so status quo, so ordinary. A majority of the Freeport city council appears buffoonish and crass-stumbling through the eminent domain process-compared with Wright’s valor and cunning. Wright III not only created a Web site describing the city’s master plan and the agreement to build the marina; he also included personal information about Royall. Royall’s attorney notified Wright III of Texas’ libel laws. Instead of ceasing and desisting, as Royall’s counsel advised, Wright III cranked up the pressure and rented a 40-foot billboard on the main thoroughfare into Freeport to advertise the site.

The Gores speak clearly and compellingly. They don’t require Main’s efforts at glorification.

Pappy said that in the beginning days of Western Seafood, he worked “from can ’til cain’t.” The family spent more than $368,000 in legal fees fighting off the eminent domain challenge. It litigated through state and federal courts for three years, instigated six citizen petitions, and attended 50-plus council meetings in Freeport. Friends become adversaries, and allies were few. Freeport’s leaders ostracized them. Doubtless, they suffered. The facts are sufficient. Main’s commentary and characterization distract.

The Gores at least had the resources to fight back. Most property owners and small-business owners don’t have that option, or can’t exercise it to the extent the Gores did, to obtain a somewhat favorable court order. Main notes, “The Gores were unusual as a family whose property was targeted for an economic development taking, because they had some means to fight the city.”

Before the reader assumes Western Seafood is an isolated circumstance, though, Main offers a legal lesson on eminent domain.

She begins her historical tour with the American Revolution, James Madison-defender of private property rights-and the Bill of Rights. Referring to Madison, himself a prosperous landowner, Main writes, “The problem was, he had witnessed the war-induced frenzy of the last decade, when normally civil people had nearly gone stark raving mad, grabbing the land of their former neighbors with a fierceness that no one could have predicted.”

Main suggests that Madison tried to draft against majoritarianism in the first 10 amendments the Constitution partly for self-preservation, partly because of political leanings. She hints that he never foresaw the present-day flip in the balance of power in the exercise of eminent domain, where the rich and their property are rarely the intended takings.

It is impossible to evaluate government’s exercise of its eminent domain powers as a liberal-for, conservative-against issue, Main correctly notes. The U.S. Supreme Court handed down its 5-4 decision in Kelo v. New London, Connecticut in 2005, holding that taking private homes and property for economic development falls within the “public use” clause of the Fifth Amendment. Backlash ensued. Main cites a public opinion poll showing those on political right and left were equally aghast at the court’s decision, with 98 percent of Americans disagreeing. Goodbye single-family dwellings on the Thames River in Connecticut. Welcome “hip little city” to New London, and welcome more legal problems for the Gores in Freeport.

Pappy died in 2006, before a judgment. Later that year, a U.S. Court of Appeals sent the Gores’ case back to state district court. The appellate court wanted the district court to consider its ruling in view of a new eminent domain law passed by the Texas Legislature in response to the Kelo decision. After years of fighting, the city of Freeport offered to build a public marina around the Gores. It wouldn’t take Western Seafood’s land after all. The city would also reimburse the Gores for their legal fees. The Gores would keep their land adjacent to Western Seafood, giving the city right of first refusal on it, and would sell the city another 100 linear feet of land downriver from the business.

But like a movie that ends with unresolved issues begging for a sequel, Bulldozed ends with the Gores offering to lease the 100 feet of land instead of selling it outright. The legal challenges reignite as the story ends.

Bulldozed demands a part two, but in the interim, the lawyers in this case will not grow weary of growing wealthy off legal fees.

Cynthia Hall Clements is a writer and second-year student at Texas Tech School of Law in Lubbock.