A Gentle Soul, Unbroken by Injustice

“I haven’t had a chance to cry yet.”- Billy James Smith

His sincerity, the sentimentality of his answers, stunned me.

I called Billy James Smith on the one-year anniversary of his release from prison to talk about his wrongful conviction for aggravated sexual assault, the 19 years and 11 months of his life wasted for a crime he didn’t commit, the proclamations of innocence no one wanted to hear. I anticipated-wrongly-a rant against the ubiquitous “system,” at least some residual anger, perhaps an occasional sarcastic snip. How else would you expect a wrongfully convicted man to react when finally released?

Instead, I got a seemingly innocuous dialogue, like a coffee shop chat with a new acquaintance.

How is the weather in Dallas? Smith lives south of there.

What did you do today? He was at his sister’s apartment-he lived with her before his arrest in 1986 for sexual assault, and again after his release on July 7, 2006. A year later, he was moving his few belongings into his own apartment that evening. Could I call him back the next night, when he would have more time to talk, he asked in a quiet voice with near-perfect enunciation. He thanked me for calling, a Southern gentleman charming me.

It was the tone of Smith’s voice that compelled me. It was the way he said, “My own apartment,” prideful but not haughty, almost in childlike awe. It was anticipation I heard.

Since his release, Smith had been unable to rent an apartment or house, despite working full-time at an auto parts store for several months after his release.

It’s easy to rent a place, I think to myself. Pay a deposit. Turn on the electricity. Move in. Naively, I had forgotten the criminal background checks most property owners conduct.

Smith’s check says “convicted” of rape on Feb. 5, 1987. His background check also says “exonerated,” but most landlords didn’t read that far.

“Over the past year, I’ve had a time renting an apartment,” Smith says with a trace of exasperation.

Gov. Rick Perry has not pardoned Smith, though DNA testing on the biological evidence from the victim’s rape kit proved Smith was not the perpetrator, and though the Court of Criminal Appeals set aside his conviction last December.

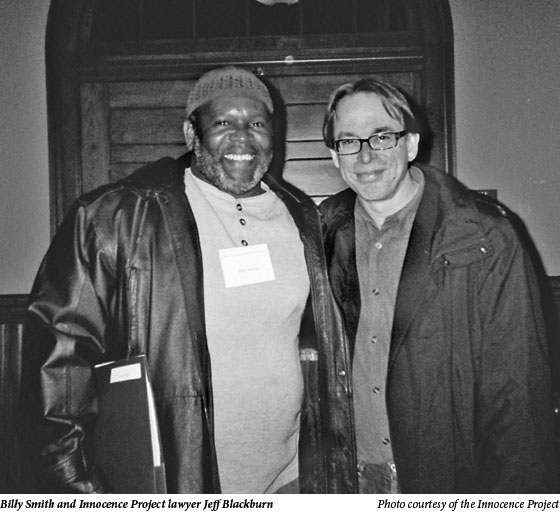

Smith’s attorneys, at the law offices of Kevin Glasheen in Lubbock, are pursuing a pardon. A little compensation from the state of Texas would be a gracious apology, as well.

Smith is most concerned about righting the injustice to his name, so it’s not “Billy Smith comma rapist” for the rest of his life.

At 55 years old, Smith is a man in legal purgatory, unable to move forward with a new life because he’s stuck justifying the false label a jury slapped on him so long ago.

It’s the quandary of the wrongfully convicted. Prove yourself innocent, again and again, and one more time, please. “I’ll be explaining this the rest of my life,” Smith says.

“People just prejudge you,” he says, referring to how the “outside” world-outside prison walls-still sees him as guilty, though he’s demonstrably innocent. Smith wants a pardon from Perry, he says, “so I can go on with my life.”

Smith candidly, somewhat casually, reveals his life before this conviction. No hiding behind platitudes and philosophies, no trying to justify his criminal activity-neither offense was a sex crime. In a previous life, he freely admits, he was guilty.

Did you do these crimes, Mr. Smith? Yes, I did, period. I was drinking and drugging, he says. There’s no “but,” no “because” in Smith’s sentences, his train of thought, no hesitant pause where you would expect the excuses to begin. It was me. I own those crimes. The mistakes were mine. I deserved punishment.

Smith’s confession makes him a man now.

Smith was behind before the race-the rush to convict an innocent-began, handicapped by who and what he was.

The rape victim’s boyfriend, who was not at the scene of the crime, identified Smith as the attacker. An eyewitness identification by someone who didn’t witness the crime was curious evidence.

Smith said he knew the boyfriend before the attack, but “never saw” the rape victim. On August 7, 1986, Dallas police arrested Smith. He was the victim-not the only victim, but along with the raped woman, a victim nonetheless-of an eyewitness misidentification. Unable to make bond and denied access to court-appointed counsel for nearly a month, Smith loitered patiently in jail, waiting for trial and the truth. Only after another inmate helped him prepare a handwritten letter requesting a lawyer did the court appoint one.

Justice, too often, is as good as you can afford. Money is a way of quantifying the nebulous ideal of “justice.” It greases things along in the criminal justice system.

Smith saves his contempt-maybe that’s too strong a word, perhaps it’s more like frustration-for his court-appointed trial lawyer, the second to defend him. The first withdrew, leaving Smith with less than second-best in his second lawyer.

Smith recounts with disdain and a little disappointment that he didn’t meet his lawyer until the day the court convened to empanel a jury for his case. He waited, hopeless and helpless, on his savior, who never came.

The attorney didn’t contact Smith’s sister, his alibi witness, before the legal browbeating began. She testified at trial that she and he were at home at the time of the crime, he asleep on the couch, she doing personal paperwork in the kitchen. Did her true story seem surreal to jurors, who were likely jaded or realistic enough to expect a relative to lie?

Bizarre, but Smith’s attorney refused to allow his sister’s neighbor, subpoenaed by the defense and also an alibi witness, to testify at trial on Smith’s behalf. “Sorry for the inconvenience,” Smith recalls his lawyer telling the neighbor in the courtroom corridor before sending him home.

What was it like, Mr. Smith, when the jury came back with the verdict?

“I slumped down in my chair in awe,” Smith says with a catch in his voice.

Twenty years ago became yesterday, when he was first convicted and sentenced, as he retold his story. His emotion was real, raw, and caused me to cry, which Smith couldn’t know, not from the other end of the phone.

The jurors not only made Smith a rapist of a woman with whom he never had sex. They proclaimed him a liar, because they chose not to believe testimony offered in his defense. They favored an eyewitness who wasn’t there and sentenced Smith to life in prison.

A rapist and a liar, Mr. Smith, but which hurt worse? Probably the latter, he says, because he knows the former to be false. “Rapist” is because of something you do. “Liar” is what you are.

Smith did his time at the Ellis Unit in Huntsville. It’s known on the streets for being particularly brutal because of its inhabitants. He did his entire prison stay there.

After the court denied his direct appeal, Smith lost his future, at least any prospect outside prison walls and fences. Broken and broke, he couldn’t afford a trial transcript to pursue his own appeal. How typical: The poor languish. The prosperous buy a ticket to the legal game and get a chance to level the playing field.

What is prison like, Mr. Smith? “Prison life was really sad for me,” he says. He says he thought often of committing suicide.

Smith would “wake up every day and go through the rugged schedule, the dangers of prison life, knowing nobody is going to believe you.” He spoke of the gangs, drugs, violence, and the prostitution, heterosexual and homosexual, he encountered in prison. It’s not an atmosphere, a place, for the emotionally or physically weak. It’s Darwinism at its most primal level, a distinctive form of evolution for the criminally inclined and the innocents trapped there. Only the evil and its doers survive, and maybe an innocent or two.

The incarcerated Smith made positive, life-affirming choices-to work, to continue his education beyond his GED, which he earned while doing his first prison time, on a robbery conviction. He held onto his faith as a recently-converted and devout Muslim. He chose busyness over despair.

His voice peaceful, serene, Smith says he knew “God was going to make it (his incarceration) right for me.” Somewhat incredulously to me, he believes his wrongful conviction was “God’s plan” for his life.

In 2001, Smith sought DNA testing to compare it with evidence from the victim’s rape kit. The Dallas County district attorney opposed Smith’s request, and the criminal district court denied his request. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals granted it four years later and ordered the DNA testing. The state of Texas was forced to admit it had made a mistake.

How do you feel now, Mr. Smith, now that you’re released and exonerated? He realized before he got out he had to “let go of hate,” including hating “the woman who lied” and said he raped her. But excited? “I wasn’t excited about getting out,” he says. Because, he says, his voice oddly flat, devoid of emotion, “it [prison] just left me empty.”

How’s life on this side of freedom treating you, Mr. Smith? “It’s really scary,” he says. The incarcerated, especially the wrongfully convicted, calculate time differently behind closed doors and in the presence of armed guards.

“I realize,” Smith says, “how far behind I am,” referring to technology from ATM machines to cell phones. His niece showed him how to enter names and phone numbers in his cell phone’s address book.

On a street corner in Dallas earlier this year, Smith stopped a stranger to ask for directions while making a delivery for the auto parts store where he works. The man rattled off a right and a left, a north and a south. Smith wasn’t familiar with the street names, and the man sarcastically asked Smith, “Man, where have you been?” Smith was too embarrassed to tell him.

How do you answer “prison” and say you were wrongly convicted in the same sentence?

How does your story end and your life begin again, new friend?

“I’m taking one day at a time and not trying to get there in a hurry,” he says.

Smith has a woman friend with whom he goes to the movies, to dinner, and occasionally the park. He attends religious services at his mosque on Friday mornings, when he’s not working, and prays five times daily as required by his faith. Smith is considering leaving the Dallas area when he gets his pardon, to find anonymity, some peace.

Smith never mentions any compensation he will receive from the state for his wrongful imprisonment. He never mentions a civil lawsuit he’s filed. He’s not expecting much to come of either. It’s not cash that’s Smith’s concern; it’s his character, clearing his name.

Even after earning his freedom, Smith says, “A lot of times, I’m not happy.”

A proverb teaches, “The soul weeps the tears the eyes can’t.” Maybe Smith doesn’t outwardly cry about his wrongful conviction, about the injustice done him, but he carries the pain in his spirit.

“I haven’t had a chance to cry yet,” Smith says at the end of our conversation, before he invites me to call back one day soon.

Maybe one day soon he’ll get that chance.

Cynthia Hall Clements is a writer and a second-year law student at Texas Tech School of Law in Lubbock.