Buffaloed on the Bayou

Revitalization Meets Real Estate Speculation in Houston

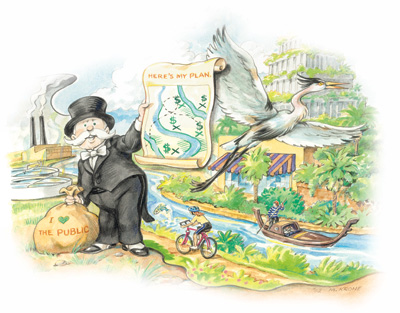

The City of Houston began 266 years ago, so the story goes, as a real estate speculation scheme along Buffalo Bayou. After founding their city at the confluence of Buffalo Bayou and White Oak Bayou in 1836, brothers Augustus and John Allen promoted Houston all over the world as a warm-weather paradise of pristine beaches, rolling hills and placid lakes. Lured by that image, settlers purchased land at inflated prices from the Allen brothers and arrived to find, not paradise, but, well, Houston–flat, humid, swampy, and 60 miles from any coastline.

Now it seems something similar is happening on Buffalo Bayou–a beleaguered little waterway that rims downtown and that a lot of influential people believe is the linchpin to the city’s continued renaissance. But while the Houston business community is hyping the bayou as a possible world-class waterfront, the very creators of this publicly-funded redevelopment plan have grabbed bayou-front real estate that might make them rich–or richer, anyway. It’s a campaign some people believe is part of a real estate speculation scheme in the finest Houston tradition.

Community leaders have long had their eye on Buffalo Bayou; more than 20 bayou redevelopment plans large and small have surfaced since the 1930s, none amounting to much. But the city may finally be serious about bayou redevelopment–emphasis on ‘may.’ As with many things in Houston, the legitimacy of the bayou plan and the motives behind it vary with who you’re talking to and with whom that person is connected.

Since 1986, development along the bayou has been the domain of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership, a public-private nonprofit foundation run by some of Houston’s most influential business people. In late September, the Partnership rolled out its Buffalo Bayou Master Plan, a document long on ideas and short on detail, and saddled with the Buck Rogers-like title, “Buffalo Bayou and Beyond.” It’s a whopper of a proposal: $800 million in public funds and 20 years of construction to redevelop a 10-mile stretch of river from Shepherd Drive in the west to the Houston Ship Channel in the east. The plan envisions cafes, restaurants, outdoor theaters, mixed-income housing developments, walking bridges, bike paths, public parks, a botanical center along the bayou, and flood-control canals to protect all this from the first big storm. The planners hope the project spurs an additional $5.5 billion in private investment along the waterway.

Once the plan went public, everybody who’s anybody in Houston lined up behind it, including Mayor Lee Brown, County Judge Bob Eckels, a horde of the city’s wealthiest business people, and the Houston Chronicle editorial board. “All over the world, great cities are reinventing themselves around their waterfronts,” reads the introduction to the more than 200-page master plan. “Think of New York’s harbor, Chicago’s lakefront, Baltimore’s inner harbor, San Francisco’s bay, Barcelona’s seafront, Paris’ Seine riverfront, and London’s South Bank and Docklands.”

The Chronicle was no less effusive in its September 22 front-page spread about the proposal. Reporter Mike Snyder’s lead painted an idyllic scene: “Disturbed by the sound of the approaching boat, a heron stirs from its perch and takes flight, its broad wings flapping just inches above the water’s glassy surface. Mullet jump from the bird’s path. A warm September breeze sighs through the trees.” The story neglected to mention that Chronicle community relations director Lainie Gordon is a member of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership executive board, according to group documents, or that former Chronicle publisher Richard J.V. Johnson was on the board as late as 1999, according to the group’s tax returns (facts first reported by Richard Connelly of the Houston Press.)

“This plan is a fabulous, visionary catalog of opportunities,” gushes Harris County Flood Control District Director Mike Talbott, whose agency helped develop the master plan. Mike Garver, a prominent local businessman and former chairman of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership, told the Chronicle that the plan was certain to bring development to the bayou. “People love water,” he said.

To anyone who’s actually seen Buffalo Bayou, this might sound slightly ludicrous. Herons, mullet, and sighing breezes aside, the bayou is a narrow, pollution-saturated drainage ditch that slithers through downtown and into the Ship Channel almost unnoticed–that is, unless you catch a whiff of the sewage treatment plants that dot its banks.

Sure, the bayou’s not without its mucky charm. But the Seine it’s not.

That has not deterred the Buffalo Bayou Partnership from staging a public relations campaign of the first order–a glossy effort to get the public behind the $800-million project. But there’s more going on here than marketing hyperbole: this is Houston, where no public works project this size could slip by without someone trying to snag a boatload of money behind the scenes. An investigation by the Observer reveals that several backers of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s master plan may benefit handsomely from the $800 million public project. A handful of current and former members of the Partnership’s executive board, men influential in developing and lobbying for the plan, have snatched large swaths of real estate for themselves along the very bayou they’re planning to redevelop, according to Harris County records.

In addition, a dozen Houston sources criticized the Buffalo Bayou Partnership and its master plan on several fronts. The bayou may offer great possibilities for Houston, they argue, but not with this plan: the development ideas are unrealistic and favor economic investment over environmental interests, parts of the flood control proposals don’t make much sense, and the Buffalo Bayou Partnership has a poor track record with spending government funds efficiently and effectively on prior projects along the bayou. Behind the grand pronouncements and references to the Seine, they say, the Buffalo Bayou Master Plan is mostly a shell game for real estate speculation by some of Houston’s most prominent businessmen, and a boon for developers at the expense of water quality, wildlife, and green space along the bayou.

Said one source, who works closely with the city and asked not to be identified, “This is the Enron of the nonprofit world.”

Of all the promoters of the redevelopment plan, Mike Garver may have the most to gain. He owns BRH-Garver Inc., a Houston-based construction outfit, and dabbles in real estate on the side–a search of Harris County land records reveals 34 properties listed under Garver’s name or his C.M. Garver Trust. Since 1995, he’s been a driving force behind redevelopment along Buffalo Bayou, serving as unpaid chairman of the Buffalo Bayou Partnership until last winter.

A search of more than 700 city and partnership documents, obtained by the Observer through the Texas Open Records Act, reveals that the day-to-day operations of Buffalo Bayou Partnership have been run chiefly by two people: Garver and Partnership president Anne Olson. Almost every partnership memo in city records was written by Olson or Garver, and one of them always represented the partnership at meetings and presentations. Perhaps no single person exercised more influence in shaping redevelopment plans along the bayou than Garver, and he remains a large contributor to, and consultant for, Buffalo Bayou Partnership. As Olson is quick to point out, Garver voluntarily undertook this important public work, efforts that earned him local awards and high praise in the community.

But it could also earn him a lot of money. During his tenure at Buffalo Bayou Partnership, Garver focused his personal real estate interests around the muddy waterway his own nonprofit was plotting to resurrect. Between 1996 and 2001, Garver purchased at least five land parcels either directly on or near the bayou, according to county land records, totaling more than 16 acres–a considerable holding in the middle of the nation’s fourth-largest city. In 1996 and 1997 he made three small acquisitions totaling a mere four acres. But on October 11, 2001, Garver bought Montgomery Ward’s old East End warehouse at 2800 Clinton Drive and the adjacent property at 88 Jensen Drive. The two tracts, which sit right on the bayou’s banks, total 12 acres. In a hearing last summer, the properties were valued at more than $540,000, a slight increase over past assessments, according to the Harris County Tax Assessor Office.

The 12-acre site resembles the many abandoned commercial lots in the area: a fenced-off derelict building, crumbling concrete, and legions of weeds. But Garver’s investment would earn piles of money if even some of Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s redevelopment proposals for the East End are implemented. The master plan’s spiffy brochure outlines a vision in which the Montgomery Ward site is immediately adjacent to a commercial development and a mixed-income housing community, in the midst of a rebuilt and enlivened area. The new neighborhood would include two parks, a wetland, a new transit stop, a boat launch and, just a couple blocks down river, a new symphony hall–plans Garver was influential in creating, and which were paid for almost entirely with public money. The master plan alone cost $1.4 million, according to the partnership. Welcome to the world of real estate speculation, in which redevelopment (or even the well-hyped prospect of it) could cause the value of Garver’s land to skyrocket, whether he chooses to develop it himself or sell it to someone else.

Garver didn’t respond to repeated calls from the Observer. When asked about his real estate acquisitions, Anne Olson said, “I’m not going to comment on one specific person. Many members of our board own property on the bayou. We’d be crazy if we didn’t have property owners along the bayou on our board. We’ve had to work really closely with the property owners. We have strict policies and procedures. If they have a conflict, they can’t vote on a certain issue. Everyone on our board knows what everyone else owns.”

In fact, several of the partnership’s financial contributors and board members do own land along the bayou, the most prominent being Halliburton/Brown & Root, the giant oilfield services conglomerate. All of the landowners stand to profit from bayou improvements, but none of the other board members had Garver’s influence on planning and lobbying for the proposal, and few purchased land so recently.

Another land holder who stands to benefit greatly from specific aspects of the plan is multimillionaire developer Richard Weekley. The bayou master plan calls for removal of a bridge called the Elysian Viaduct, which connects with Highway 59 and serves as a vital link to downtown for poor East End communities. Olson says the partnership wants the bridge removed because it’s falling apart and its absence would clear room for green space and parks. But it’s worth noting that the bridge bisects a 12-acre plot on the bayou owned, according to county records, by a company called 12.3 Buffalo Bayou LP, a real estate concern chartered by Weekley and two associates. One of the top Republican political donors in the state, Weekley is perhaps best known for founding the Texans for Lawsuit Reform political action committee, and for heading the business community’s Houston Quality of Life Coalition. He also sits on a Buffalo Bayou Partnership planning committee, according to group documents. The removal of the bridge would open for development Weekley’s holdings, land that’s already increased in value 82 percent since 1998, according to county tax records. Weekley didn’t return calls from the Observer seeking comment, but said through a spokesperson he had no involvement with Buffalo Bayou Partnership, aside from several meetings he was asked to join.

Olson noted many of the land owners, including Garver, have promised to donate right-of-way space on their property for Buffalo Bayou projects, including parks and bike trails–space the Partnership or city would otherwise have to pay for. But records indicate that not everyone connected with the Partnership planned to donate right-of-way. In a 2000 proposal to TxDOT, the Partnership planned to pay more than $500,000 to purchase right-of-way from five land owners–one of which was Weekley’s 12.3 Buffalo Bayou LP–for a proposed bike trail, according to city documents obtained by the Observer, though the project was later nixed due to design problems.

Few of the nearly 30 sources interviewed for this story would speak on the record about Garver’s apparent conflicts of interest, fearing political and economic retribution from the Houston business establishment. But many sources privately expressed concern over Garver’s land grabs and indicated that many people within Houston’s business community knew of and consented to Garver’s activity–some sources said it was viewed as compensation for Garver’s good work along the bayou.

Barry Reese, former chairman of the Houston Bicycle Advisory Committee, harshly criticized the Partnership. Though they were supposed to be working together, Reese had several run-ins with the Partnership over proposed bike trails along the bayou. “It became clear that this was only benefiting one man or a small group,” he said. “For me, it seems like a grab for cash and … a grab for land that will be entirely valuable.”

Trying to convince Houstonians that Buffalo Bayou could be their version of the Baltimore waterfront isn’t cheap, apparently. In all, the “Buffalo Bayou and Beyond” master plan required roughly 18 months and $1.4 million to put together. The city, county, and Partnership pitched in $350,000 each, and the Harris County Flood Control District added $400,000, meaning the master plan was almost entirely publicly funded, even as tight budgets have cut funds for most local government endeavors. Despite the high cost, the master plan, created for the Partnership by Boston-based Thompson Design Group, is a remarkably fuzzy document. It contains few specific action plans, timelines, feasibility studies, or plans to obtain funding. At this point, the Partnership figures $500 million will come from federal flood control funds, with city, county and private contributions filling in the rest.

Even its harshest critics swoon at some aspects of the plan–what’s not to like about turning the Northside Sewage Treatment Plant into botanical gardens? But there are serious questions about the project’s feasibility. Beneath all the hoopla, the proposal essentially has three components: creation of parks and public art facilities, development of mixed-income housing, and enhanced flood-control. In addition to the botanical gardens, other highlights include an open-air symphony hall on its own island; ecology parks on each bank; recreational boat launches; a downtown amphitheater; reconfigured bayou crossings; a Commerce Street promenade; a reworked Allen’s Landing with boathouse, visitor center and restaurant; a series of west-side wetlands; and a bevy of mixed-income housing developments. That’s just a sampling; the design also reconfigures highway interchanges, refurbishes (or, in some cases, removes) bridges, and adds bike paths.

To some it seems a bit pie-in-the-sky; to others it’s simply a boondoggle for developers. “This is a development plan,” says Clark Martinson, a planner with HNTB Engineering who’s worked on several bayou projects. “It’s a truly fantastical vision.” He said he was disappointed that development, rather than park land, dominates the proposal. He seemed skeptical the current proposals would ever become reality. “That plan is just a plan to get people to think d

fferently about the bayou,” he said. Two other critics echoed Martinson’s v

ew that the plan favors economic over environmental development. In other words, they said, the plan is more San Antonio Riverwalk than Austin Town Lake. And they wondered why the plan contains nothing to reduce pollution in the watershed.

Critics also cite the Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s poor track record with other, less ambitious, publicly-funded projects along the bayou. The City of Houston and Harris County currently contract with Buffalo Bayou Partnership for help building bayou bike trails. Under those contracts, according to city records, the Partnership has received $60,000 a year ($30,000 each from the city and county) since 1995 to facilitate the building of trails along the bayou, a mandate that includes meeting with community groups, obtaining right-of-way commitments from neighbors, contracting consultants and creating a newsletter. In this equation, the Partnership is essentially a middle man, a role for which the Partnership has been paid a total of $420,000 during the past seven years. It’s a nice gig.

Yet hike-and-bike trail projects along the bayou have stumbled in recent years, according to city documents and several sources. One example is the trail project that was supposed to run from Baker Street to North York Street on the bayou’s north bank, a project sponsored and planned by the Partnership. Community relations, budgeting, and securing landowner support are Buffalo Bayou Partnership’s responsibilities on this project, according to city contracts. Yet the project is over-budget, and has suffered delays and modifications after local landowners refused to cede right-of-way for the trail. One particular right-of-way mix up involving Union Pacific Railroad forced planners to shorten the trail and “was probably an oversight by Buffalo Bayou Partnership,” said Mark Patterson, project manager with TxDOT’s Houston district. These hiccups have already cost Houston taxpayers and beg the question: If the Partnership had trouble with a $2 million hike-and-bike trail, how well will it handle an $800 million, 20-year public works adventure?

For her part, Olson says the bike trails are mainly city projects that the Partnership has little to do with. She defended the Partnership’s record, which she said included raising $40 million in private funds for work on Sesquicentennial Park, supporting the new Sunset Trail along the bayou, and contributing to the Allen’s Landing redevelopment project.

Another area of concern for skeptics is the flood-control proposal, which is a centerpiece of the Buffalo Bayou plan. Unlike San Antonio’s Riverwalk canal, which is dammed off and carefully controlled, Buffalo Bayou floods after nearly every heavy rain. While they can’t eliminate flooding on the bayou, the Partnership and the Harris County Flood Control District hope to reduce levels enough to allow development near the bayou, if not on it, an approach that makes some critics wonder if development is driving the flood-control design and not vice-versa.

The flood-control plan has two main elements, both designed to increase the amount of water the system can handle: widening the bayou channel and carving two “bypass” canals. These canals not only help with flood control, but also present prime water-front spots for the Partnership’s development plans. Steve Fitzgerald, the flood control district’s chief engineer, said the agency worked with engineering consultant Turner, Collie and Braden to develop the flood-control plan. Turner Collie and Braden is headed by Jim Royer, a past president of the Houston Downtown Partnership, and a major player in Houston politics. Fitzgerald said the agency used complex computer modeling to design the plan and hopes to reduce flood levels by five feet at Main Street in downtown.

Jim Blackburn, Houston’s resident tell-it-like-it-is environmental attorney, is suspicious of the plan, observing that the proposal’s call for a south canal will have no flood-control benefit, but makes for nice bayou-front development. “The south bypass doesn’t make too much sense,” concurs Larry Dunbar, a Houston hydrologist and engineering consultant who occasionally works with Blackburn on projects. “It appears the southern bypass is more for development along the bayou than for flood control. It’s not a wise investment.”

Mike Talbott, the flood control director, and Anne Olson conceded they were rethinking the south canal after the initial criticism. And Talbott added that the flood control district still must conduct a cost-benefit analysis to determine which elements of the plan provide the most flood-control relief relative to cost. That wasn’t very reassuring for Blackburn. “You’d think for a million dollars they would’ve done a feasibility study,” he said.

The big question here remains: Is this a development proposal with flood control built in or a flood-control plan with redevelopment as nice side benefits? The fate of the development-friendly south canal should reveal the answer. The south canal’s survival would indicate developers, not the flood control folks, hold the master plan strings.

And if the developers are running the show, will anything ever come of all this, other than inflated land values along the bayou? It’s still early in the game, but the Buffalo Bayou Partnership, the City of Houston, and the Harris County commissioners soon will have to move toward the nitty-gritty of turning the master plan’s fantastical concepts into reality. It’s a process that should reveal the proposal’s true identity as either a genuine effort to rebuild Houston’s waterfront, or an over-hyped real estate speculation scheme of which the Allen brothers would have been proud.

Dave Mann is a freelance writer in Austin.