Can Labor Candidates Help Texas Dems Win Back Power?

A slate of union-affiliated candidates are taking the labor movement on the campaign trail up and down the ballot.

After pulling off an upset special election win for the solid-red Tarrant County Senate District 9 in late January, Democrat Taylor Rehmet told his cheering supporters at the Nickel City bar in Fort Worth: “This win goes to everyday working people.” The local Machinists’ union president beat his right-wing Republican opponent Leigh Wambsganss by 15 percentage points in a district Trump had won by 17 just two years ago. Wambsganss had raised 10 times the amount Rehmet raised for his campaign.

Democrats have been looking for a path forward since facing devastating losses two years ago—including by redoubling their efforts to shore up support among working-class voters. Rehmet’s stunning victory has not just energized the Democratic Party heading into the 2026 midterms; it’s seen as proof of concept for an upstart slate of candidates who have come from the ranks of organized labor to run for office and, ideally, shake up the status quo of Democratic politics in Texas.

“People are tired of the same old politics,” Leonard Aguilar, the new president of the Texas AFL-CIO, told the Texas Observer in an interview in early February. The state labor federation announced its 2026 primary election endorsements in January. “The working people of Texas are looking for somebody that is actually going through what they are, who can understand what their kitchen table issues are and make sure they have somebody that fights on their behalf. That’s what Taylor and the other labor candidates are about.”

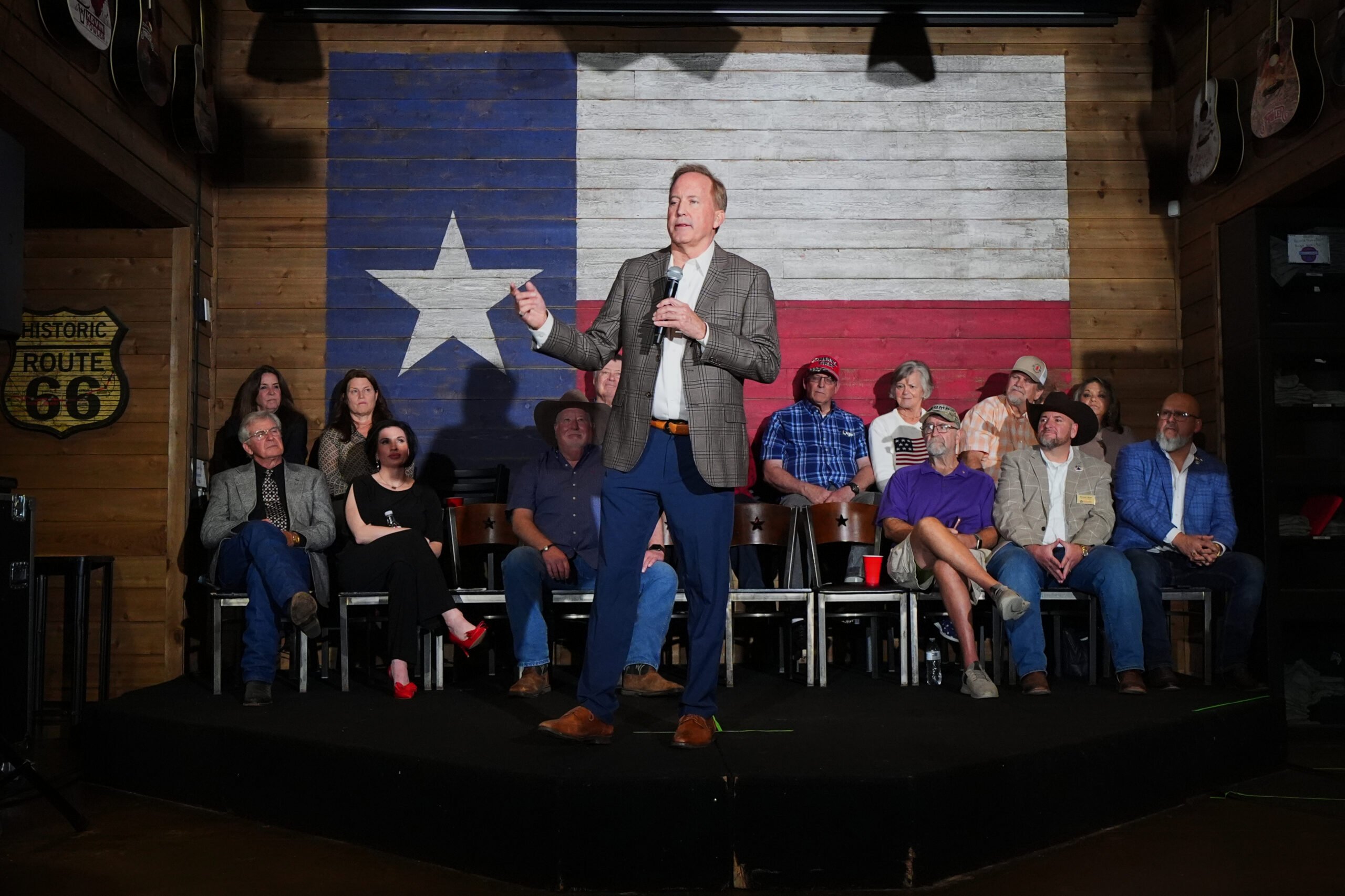

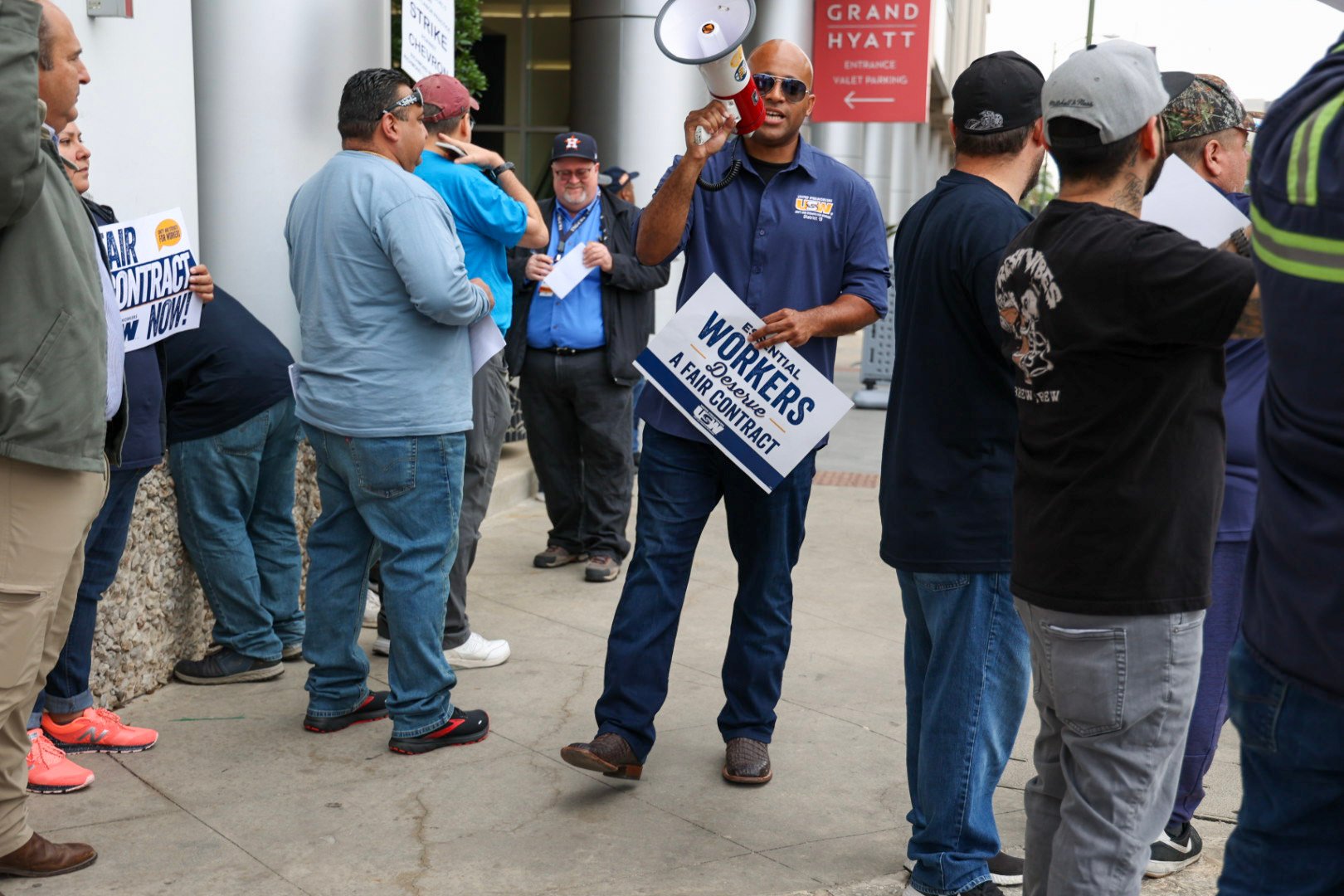

Take, for instance, Marcos Vélez, a Gulf Coast region labor leader-turned-upstart candidate for lieutenant governor, who made some waves when the Texas AFL-CIO endorsed him last month over four-term Austin state Representative Vikki Goodwin. These days, Vélez’s day job as the assistant director of the United Steel Workers District 13—which covers the union’s workers in Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico—starts before dawn and goes until the afternoon when he begins campaigning for lieutenant governor for the rest of the evening and weekends.

“You have working people all over the state of Texas that work 16- to 18-hour-days, and they can barely keep food on the table. So I’m not going to complain, because I’m very blessed for the job that I have, and it’s going to take long hours to get this done for the people of Texas,” Vélez told the Observer at his Steelworkers union hall in Webster.

Vélez, whose parents are Puerto Rican and Black, grew up in nearby Pasadena. He graduated high school early and ended up cutting his college career short to work in an oil refinery. And he’s got countless harrowing stories to tell from those days: of coworkers who had their fingers sliced off or whose bodies were scorched by machine fires. These experiences motivated him to start advocating for other workers, become a union organizer, and, now, run for lieutenant governor. “Those are the kind of things that really move you, where you say ‘You know what—people deserve better,’” Vélez said.

Vélez has seen firsthand the fallout of today’s turbulent economic conditions: Many Steelworkers members have been out of a job for half a year, and even his own son is delivering pizzas after graduating with a college degree. Vélez is a political novice who, in his first bid as a candidate, is boldly vying for one of the most powerful offices in Texas. But he said he didn’t see any other choice than to run for lite guv—as it’s known by Capitol politicos—which presides over the Texas Senate and controls the upper chamber’s legislative agenda. “I’m tired of watching pro-people, pro-labor, pro-middle class legislation just die on the vine,” Vélez said.

But Vélez has a steep hill to climb. Per the latest campaign finance reports from January, he has just $51,000 cash on hand, compared to the $161,000 Democratic opponent state Representative Vikki Goodwin has raised. Incumbent Republican Dan Patrick has $38 million in cash reserves. Most of Vélez’s financial support so far is from Houstonians for Working Families, a PAC which has received a bulk of its funds from the Texas Majority PAC (TMP), the Texas Democratic Party’s top campaign partner. The implicit backing of Vélez by TMP—which has pledged neutrality in the primaries—has, per the Texas Tribune, drawn some consternation among party operatives and other candidates, including Goodwin.

TMP’s executive director Katherine Fischer said TMP isn’t playing favorites: “We’re not endorsing anyone in that race,” Fischer told the Tribune. “I think he’s a very exciting candidate, but we are primary-neutral.”

Vélez’s inexperience with legislative politics has become a key point among his critics. In its endorsement of Goodwin, the Houston Chronicle editorial board noted that the union leader struggled to name his hometown state legislators (something he’d surely need to brush up on to be lite guv but that he just as surely shares with the majority of Texans).

Goodwin, who’s been a vocal opponent of school vouchers and an advocate for public schools in the Texas House, told the Observer that her political experience is a key asset compared to Vélez. “It’s naive to think that somebody who’s never held office would be effective as the lieutenant governor,” she said. “The experience that I have will make me effective in passing the priorities that Democrats have held for a long time.” Goodwin raised her three children as a single mom, became a realtor, then won the Republican-held House District 47 in West Austin in 2018. She shares similar goals as Vélez, and both aim to break the right-wing iron grip Patrick holds over the Senate. But they said their priorities differ. Goodwin said, “Public education is foundational,” while Vélez would prioritize what he calls “people’s hierarchy of needs,” such as raising the minimum wage and affordable housing.

If anything, the message that labor candidates such as Rehmet and Vélez are emphasizing is something that other Democrats are taking note of. The races this year are “pocketbook elections,” said Brandon Rottinghaus, professor of political science at the University of Houston. “People are going to be very concerned about the candidates and how they plan to address people’s economic issues.” Texas Republicans, on the other hand, “have been slow to get the message that affordability is a huge issue,” Rottinghaus added.

Rehmet succeeded, Rottinghaus said, because he “kept it local,” he largely “ignored Donald Trump,” and talked about issues local residents cared about.

In West Texas, Kyle Rable, an Army Reserve officer and PhD candidate at Texas Tech is running as a Democrat for the deep-red 19th Congressional District, currently held by the retiring Republican incumbent Jodey Arrington. Rable, who is also a member of the Texas State Employees Union, said he’s using the same strategies Rehmet did to try to win this open rural red seat. It’s been more than 40 years since a Democrat represented District 19, but Rable said he’s undeterred because he sees low turnout, and not partisan politics, as the main problem. He said he’s knocked on roughly 3,000 doors since May, listening and talking to residents concerned about saving their healthcare, homes, and farms.

Rable rattled off ideas to break up Big Ag corporations that monopolize farming products, from cotton seeds to farming equipment and tractor repairs, and to end Trump’s tariffs “because nobody is buying American cotton right now.” Meanwhile, he said his seven GOP opponents are all trying to out-MAGA each other. “Their messaging is totally out of sync with people when the main question is: ‘Are you financially better off now than you were before?’ And the answer for almost every single West Texas that’s not an oil billionaire is that, ‘No, we’re not better off.’”

These labor candidates are bringing new life to the Democratic Party at a time when more union members are leaning toward Trump and the Republican Party. Several trade unions in Texas, including two Teamsters locals, announced their support for Governor Greg Abbott last week.

Aguilar, the Texas AFL-CIO president, said it’s even more important that these labor candidates avoid hyper-partisan politics. “It’s just not just the right versus the left. It’s about workers, and the workers’ over billionaires’ interests. That’s the focus,” Aguilar told the Observer.

Last year, the state labor federation made a concerted effort to get more union members into office by starting a candidate training school. It graduated its first class of 16 cohorts in October.

Jose Loya, another United Steelworkers organizer from the Texas Panhandle, is running for Texas Land Commissioner—the statewide office that manages state-owned lands, the Permanent School Fund, aid after natural disasters, property loans for veterans, and the Alamo. Loya’s own history reflects layered stories of working-class struggles. He immigrated to the Panhandle from Mexico at age 8 and spent his school years laboring in the fields and then in a meatpacking plant. After graduating, he enlisted in the Marine Corps and served two tours in Iraq. When he returned to Texas, he worked in oil refineries before joining the United Steelworkers.

“I’m not just an immigrant. I’m not just a veteran. And I’m not just a labor leader. I’m all those things put together,” Loya told the Observer. “I’ve had people reach out to me that work at the GLO [General Land Office] right now that told me, ‘Look, I’m a very conservative Republican. I have never voted Democrat. But I’m going to vote for you because your story is real.’”

Loya won the Texas AFL-CIO endorsement over Democratic candidate Benjamin Flores, a city council member in Bay City.

Organizing workers for a union drive is not unlike mobilizing voters to get out and vote, said Montserrat Garibay, a former secretary-treasurer for the Texas AFL-CIO, Education Austin leader, and labor liaison for President Joe Biden’s Department of Education. Garibay is running in a crowded field of candidates in the Democratic primary to serve Texas House District 49, which is currently represented by state Representative Gina Hinojosa, who’s running for governor against Abbott.

“I am approaching this campaign with an organizing lens that every person I talk to is important and that every vote is what will make a difference on election day,” she said. Garibay has a wide range of endorsements from the Austin American-Statesman, Annie’s List, and federal, state, and local officials, as well as local unions. Another union official running for the Lege in the Austin area is Jeremy Hendricks, an assistant business manager for the LiUNA laborers union seeking to replace Senate candidate James Talarico in the state House.

In total, the Texas AFL-CIO is endorsing 16 candidates who are union members (the group stayed out of the top-billed contest between Talarico and Congresswoman Jasmine Crockett).

“We’re over being told that you just have to wait and it’ll be okay when it hasn’t been,” Rable, the U.S. House candidate, said. “Nobody’s coming to save the working class and the regular American, so we might as well step up and save ourselves.”