The Arc Doesn’t Bend Itself

A new memoir traces the evolution of a trailblazing civil rights group in Texas.

A version of this story ran in the September / October 2025 issue.

Editor’s Note: The following is adapted from the introduction to The Texas Civil Rights Project: How We Built a Social Justice Movement by Jim Harrington, who in 1990 founded the groundbreaking nonprofit from which the book takes its title and led the group for the next 25 years. © 2025, published with permission from the University of Texas Press.

Some people along the way have called me a “badass.” I never aspired to be a badass and usually don’t think of myself as one. For me, my career was all about being a zealous advocate for people who are poor, disenfranchised, and oppressed. What matters is their lives, their stories, their histories, their hope, and walking alongside them on the journey toward justice.

Being part of any movement for justice, I admit, is pretty badass. That is certainly true of the Texas Civil Rights Project (TCRP) and the people with whom we collaborated. One colleague, herself a fervent activist, made her own assessment by gifting me with a pair of bright-red professional boxing gloves, which I hung from the bookcase behind my desk.

My part in TCRP is not small, but my aim is to focus the lens on what the community and TCRP did together for greater equity. TCRP always strove to focus on those for whom we advocated. Our goal was to be part of the valiant team, not its captain, making justice. Everyone helped carry the ball. I was lucky to be a player.

TCRP took guidance from individuals and grassroots organizations trying to better the lives of those around them. We did our best to be their protector, advocate, and servant leader, to take direction from them and not the other way around.

Law is a tool, not an end in itself. Justice is the goal of all human rights undertakings—everything in “right relationship,” as the philosophers and Scriptures put it. Right relationship is not status quo and does not appear on the scene without arduous struggle and fundamental social readjustment. Right relationship means the people have power, all the people.

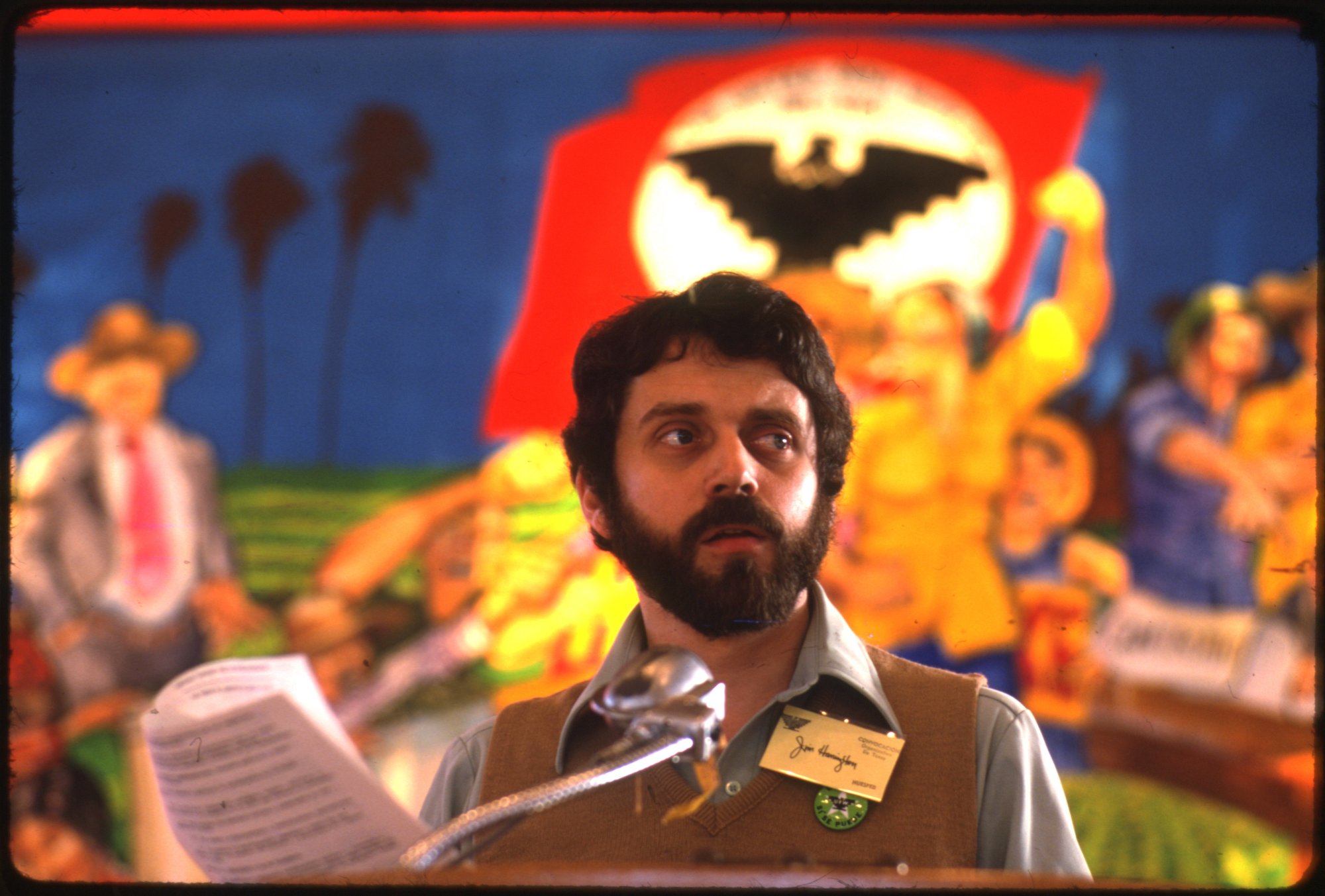

Two memories about keeping law in perspective always stayed on my mind as an attorney. One is a meeting between the labor leader César Chávez and a dozen prospective volunteer lawyers on a chilly Saturday morning in a small vacant rural house in the Rio Grande Valley in December 1976. The local United Farm Workers (UFW) branch was beginning to reorganize.

There were the customary polite handshakes and warm greetings. We all were in awe of César, of course. He was our hero. After the pleasantries, we finally sat down on old folding chairs in a circle filling out the small, empty living room of the unheated house.

César started the meeting with generous thanks and then before long made a seemingly impolitic comment, which only he could get away with, that he did not like working with most lawyers. They spent too much time telling him how various laws impeded the UFW from doing something. He wanted lawyers who would figure out how to do something when the law was an obstacle and assist the movement when the law needed bending. That memory stuck and represented for me the UFW mantra: ¡Sí, se puede! “Yes, it can be done!”

That became the TCRP mantra, too. We turned it into a verb to better convey its message: how to creatively use the law, how to think outside the box, so that the law could help, not hinder, those we served. How to sí-se-puede.

From then until his death eighteen years later, it was my privilege to represent César and the UFW in Texas and learn from him. He was a brilliant strategist at using litigation hand-in-glove with organizing. He could be charming in person with audiences but also fierce in summoning people to action. He was like a grandfather with our young kids at breakfast when he stayed overnight. He would sit at the end of the table while they were eating their cereal before leaving for the school bus and chat them up about school, what they liked, favorite class—the regular questions. He was always smiling and laughing with them.

The second memory is a pithy summary of César’s point: a wizened migrant farm laborer and dogged UFW organizer, Baltazar “Don Balta” Saldaña, expressing gleefully a few times that “we have a lawyer on our side.” He knew from experience how essential that was for any gritty organizing and hard-fought social action to join forces with a legal team.

Don Balta, as we respectfully called him, had lost his right hand in a farm accident but could still outwork any two other people. His sons and daughters, now young adults, had the same labor ethic and dedication to the movement. They migrated from McAllen to California’s fields, a broiling 1,800-mile desert drive, every year for much of their lives and were proud huelguistas (UFW strikers), whenever César needed them.

TCRP was unique in being the only community-based civil rights organization of its kind in Texas, perhaps the country. We lived under a hybrid model, blending statewide or national impact litigation with on-the-ground community legal assistance. Our emphasis was on developing and protecting human rights in Texas. Our assistance came without cost to those who needed it. Our only regret was that we had the capacity to help only about five percent of those who sought us out, such was the need.

As time barreled on, I saw more clearly that people’s struggles today lived in the struggles of those who went before. Today’s struggles, like theirs, help bend the long arc of the moral universe a bit more toward justice, as Martin Luther King Jr. envisioned. The arc doesn’t bend itself. Progress is slow, excruciatingly slow, and requires robust hope to hold greed, corruption, and power in check and help bring about their great reversal.

For me, our responsibility is not just to our community and grandkids, who follow us into a life we try to make better for them. We have a weighty duty to continue the arc-bending of the many who preceded us and who lived with the hope that we would carry forward their struggle against oppression, resisting the vortex of evil. This is how we keep faith with our inheritance from them.

Many sacrificed to get us where we are today. Many were killed, lynched (some in obscene spectacle fashion), burned, mutilated, lost jobs, and endured much, trusting that we would take the torch from them, run a marathon or two with it, and then pass the torch to the next group of runners. And no time to do a pit stop for handwringing.

I tried to work and live closely with the people I served. Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative calls this “getting proximate” on issues of race and injustice. Being proximate is as much a learning encounter as a sharing experience. In so many ways, they propelled my growth as a person and taught me much about human rights as a way of life and not just a cause.

Getting proximate, I believed, included being content with a lower salary than one might expect even for a nonprofit group. It was a good reminder of the financial stress most people face daily, which often alters the direction of their lives. If someone’s car broke down, they didn’t have to call. We depended on friends and neighbors to help fix the vehicle. Getting proximate also meant not expecting a standard forty-hour workweek.

Few were the days I did not wake up in the morning, grateful and honored to be at the people’s side. And when the work was harder than usual and the brick wall almost impenetrable, I took inspiration from them.

For those with and for whom I worked, with humility and gratitude, I offer this recollection of an era that destiny let me share with them. And that’s pretty badass.