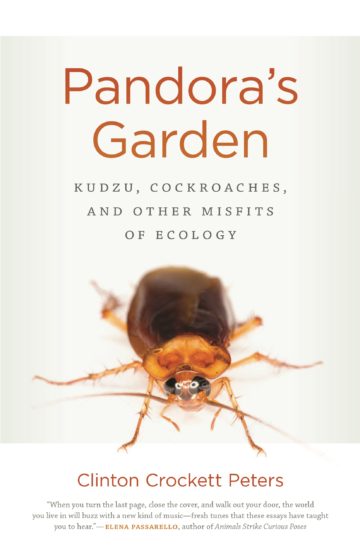

How a Texas Author Learned to Love Cockroaches (and Other Tales of Off-Putting Creatures)

Clinton Crockett Peters’ fondness for unpopular species may well temper some of our deepest prejudices.

Above: The Rattlesnake Roundup in Sweetwater.

For Clinton Crockett Peters, the first formative experience with wildlife would strike at a young age. Six years old and living briefly on North Padre Island, he met with what he calls a “spectacular splatter” on his head. Peters compares the feeling to “a hailstone of an ice cream scoop,” and his reaction was one that many an inquisitive kid might identify with: He licked some off his finger and tasted it. In colorful detail, Peters describes the suddenly horrifying event in his mouth and the “scorching” of his gums, which made him run screaming. The nefarious substance was only seagull dung, but Peters — once his shock subsided — would develop a newfound curiosity about the place of humans among creatures he’d previously paid little attention to.

by Clinton Crockett Peters

University of Georgia Press

$24.95; 192 pages

In Pandora’s Garden: Kudzu, Cockroaches, and Other Misfits of Ecology, the author channels that wonder into a number of maligned or unpopular species. These are life forms that “slither, hide, proliferate, soar above and drop their mysteries unto our heads.” The book is reminiscent of Gordon Grice’s The Red Hourglass and Robert Sullivan’s Rats, works that likewise probe the fear and folklore of off-putting creatures. The reference to Pandora in the title reflects our own role in tampering with wildlife, and in sometimes unleashing forces to disastrous effect. The relationship of humans to other species is a complicated one, and Peters identifies himself as “agnostic” on what our stewardship means. From that vantage point, his attempt to understand these creatures is as much anthropological as it is zoological.

Raised in West Texas — a place he describes as one of cotton fields, dust storms and desert beetles (he now lives in Carrollton, outside Dallas) — Peters brings together many intriguing stories of how Texans interact with so-called “misfits of ecology.” A profound example is the “Texas snow monkey,” a.k.a. the Japanese macaque, imported to a Laredo ranch in 1972 for protection and scientific study. Of the 150 that arrived, half would perish in the new and forbidding terrain; the others would not only adapt but thrive beyond imagination. Their numbers quickly grew out of control, as did many of the escaped monkeys. Peters writes, “They climbed mesquite branches and … clambered on people’s houses. Chewed up porch swings. Killed a dog, allegedly … Scared cattle. Ate cooling pies. And laughed.” Since the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department considered the monkeys invasive, hunters were initially given free rein to execute them, and some went so far as to bait the monkeys and mercilessly gun them down. Only after stories of these atrocities appeared in the media were the monkeys given protected status. Hall of Fame pitcher Nolan Ryan even helped champion the awareness campaign, which culminated in an official “Nolan Ryan Snow Monkey Day” at a Rangers game.

The relationship of humans to other species is a complicated one, and Peters identifies himself as “agnostic” on what our stewardship means.

Other tales in Peters’ book have a similarly murky sense of morality. At the World’s Largest Rattlesnake Roundup, in Sweetwater, Peters strives to be open-minded. He delves into the event’s great allure to its fans (some 50,000 yearly), hometown residents and snake handlers, but he also doesn’t shy away from graphic depictions of slaughter and evisceration. With that same sobriety he considers “katsaridaphobia,” or the fear of cockroaches, a queasiness that dates as far back as the ancient Romans and the Old Testament. In “Water Bugs: A Story of Absolution,” Peters assesses our longstanding malevolence toward these creatures for reasons both rational and irrational. He reminds us that their very presence in America is the fault of Europeans, who accidentally brought them over from Africa. While the author’s personal fascination and broader perspective on the cockroach is unlikely to absolve most readers of their fears, he may well temper some of our deepest prejudices — or at least chase these from their darkest corners.

From species to species, with a mix of the clinician’s eye and the storyteller’s voice, Peters creates a sense of wonderment about his subjects. Among his many interesting characters is a 64-year-old woman from outside Lubbock, who rescues despised prairie dogs (some 2,000, she estimates) from being drowned, dynamited or poisoned. We also meet an exterminator nicknamed “Cockroach Dundee,” who operates a Cockroach Hall Of Fame on the side, wherein he dresses up his prizes as “Marilyn Monroach,” “Imelda Marcoroach” and “Liberoachi.” In “Beasts on the Street,” Peters offers a semi-humorous, semi-serious parody of his own existence as a pedestrian and cyclist in Dallas. Calling himself an “endangered bird” among “unpredictable, mesmerizing man-eaters,” he thoughtfully parallels our routine acceptance of car fatalities to the mentality of other “predator-accustomed people,” such as those who live alongside Nile crocodiles or Siberian tigers.

Sometimes, in Peters’ desire to scrutinize human behavior and peel back man’s exceptionalism, his analogies are a bit of a stretch. His tilt toward moralizing can feel tacked on, such as when he compares primates who resist confinement to Texans who oppose gun laws or defy the “takeover strategy by the national government.” At the Rattlesnake Roundup, he takes a strange detour into our appetite for sports like football, suggesting that cameramen should follow around injured athletes to reveal the sport’s hidden brutality. Fortunately, these disruptions are rare and usually short-lived, as Peters returns to his truer talent for more subtle commentary and narrative irony.

With a mix of the clinician’s eye and the storyteller’s voice, Peters creates a sense of wonderment about his subjects.

At its best, the book relays its many cautionary tales with a combination of quixotic episodes, historical facts and surprising details. Beyond Texas, Peters extends his gaze to the rampant spread of kudzu vines in the southern United States, the explosive carp populations in the Great Lakes and the crossbreeding of rabbits in colonial Australia. (One might be astonished to learn that a million camels now roam the Outback.) By the final chapter, Peters once again invokes his original agnosticism about mankind. Calling us the “conductors of evolution,” he meditates on mass extinction and what a post-anthropocene era might look like. Somewhat drearily, he envisions a future in which “the globe limps on.”

A better assessment might be found in an earlier chapter, when Peters visits an animal reserve and theme park in Tallahassee. He observes an experienced handler surprised by the snap of a cottonmouth snake. Mike, the handler, responds with unexpected admiration. “I kind of like it when they do that,” he says. “I mean, animals lose all the time. … It’s so neat to see them stand up to us and be wild.”