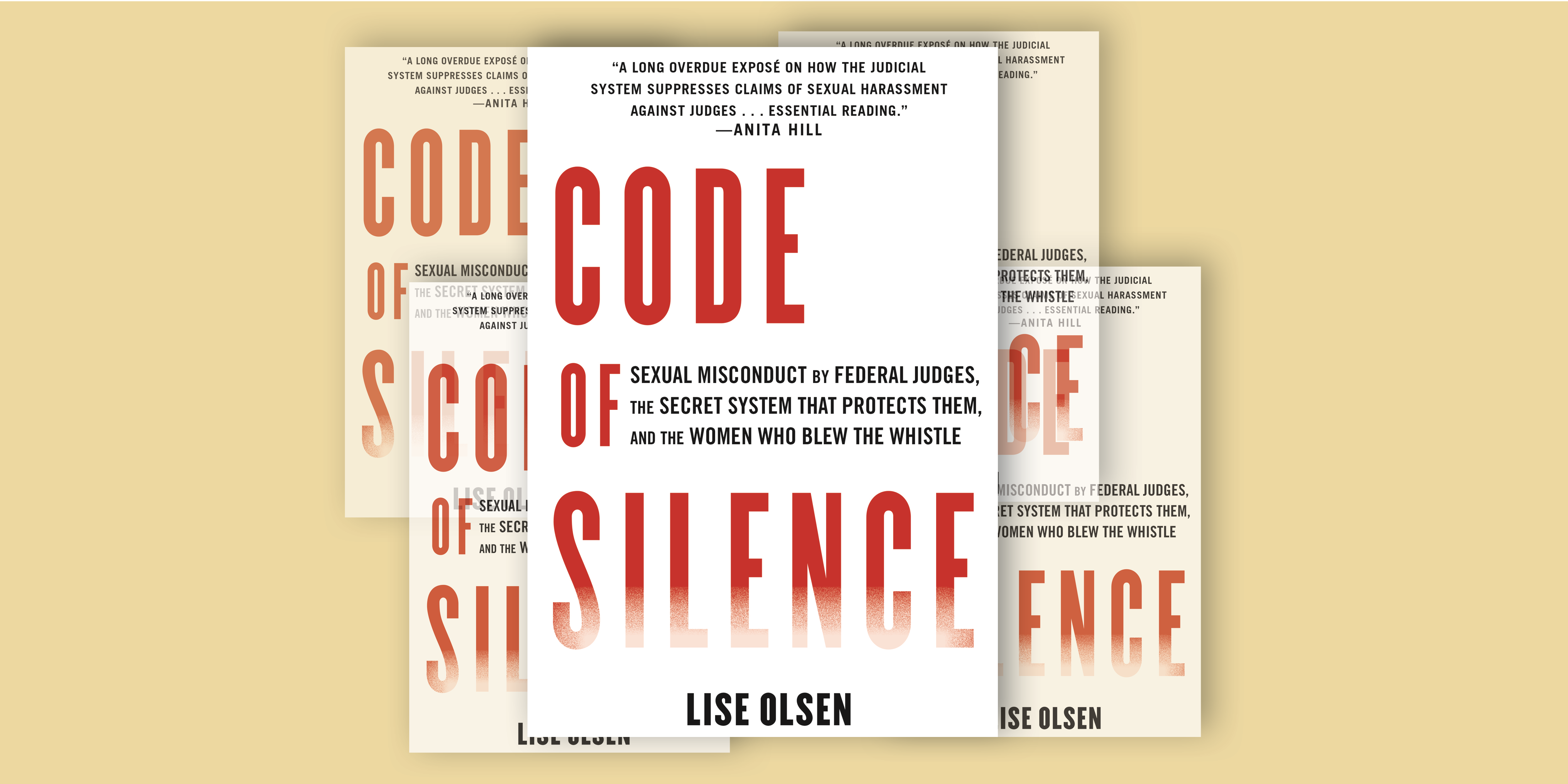

‘Code of Silence’ Reveals How Courts Systems Protect Federal Judges Accused of Misconduct

A new book illustrates how complaints are often suppressed—even in the case of a Galveston judge who sexually assaulted employees in his chambers.

I was buried in work in the Houston Chronicle newsroom when I first heard a rumor that seemed too shocking to be true: A federal judge sexually assaulted his top assistant inside a U.S. courthouse and she’d run crying from his chambers with her clothing in disarray. And no one would talk. For years, Cathy McBroom’s awful experiences remained locked inside a secret system in which federal judges review complaints about each other. As an investigative reporter and later as an author, I learned shocking details of what happened to McBroom and other victims that I could not publish—partly because sources were sworn to secrecy or feared powerful federal judges. After a years-long legal fight, U.S. District Judge Samuel Bristow Kent became the first federal judge in the nation’s history to be impeached for sex crimes—against McBroom and his own secretary—and eventually went to prison.

With the #MeToo movement, more troubling complaints began to surface about federal judges and other coverups nationwide. My book, Code of Silence, reveals the full story of the Kent case and the toll it took on McBroom, a native Texan. It also tells of other brave women whistleblowers and misbehaving federal judges in Washington D.C., California, Kansas, and many other states. Many of us heard Christine Blasey Ford testify in 2018 and remember Anita Hill’s testimony in 1991. And members of Congress have recently reacted to the Wall Street Journal’s 2021 series about judges who failed to follow federal disclosure laws or recusal rules with what seems to be complete impunity. My book explains how many other complaints of misconduct by powerful federal judges can be hidden, and the terrible implications for all when bullies remain on the bench. The following is an excerpt from Code of Silence.

— Lise Olsen

Release Date: Beacon Press, October 26, 2021

Flight

Houston and Galveston, Texas, March 2007

Cathy McBroom felt herself unraveling as she drove back to the brick house she shared with her husband, Rex, and youngest son, Caleb, in the quiet Houston suburb of Clear Lake. It was still early on Friday, March 23, 2007. She hoped to find comfort from Rex, but discovered him already asleep in his work clothes on the chest- nut brown leather couch in their living room. For a while, she sat silently beside him. He didn’t stir. She began to cry and to repeat her husband’s name, softly and then in a staccato beat. The longer she sat there, the more her anguish and anger grew. “Wake up!” she finally screamed. Still, he slept on.

Rex was often tired on Friday nights. He worked punishing ten- to twelve-hour shifts in a chemical plant, a behemoth pressure cooker of an operation that belched out smoke and fumes and operated 24/7, often in ungodly weather. He spent many long, tense workdays responding to emergencies as a troubleshooter and often arrived home exhausted. Yet on this particular Friday, Cathy McBroom felt sure he was dozing out of a desire to avoid dealing with her crisis. She was used to managing stress as the case manager for a federal judge, but felt ready to explode.

Feeling anger surge again, McBroom abandoned efforts to wake him and strode into the master bath to wash her face. McBroom felt none of the calming effect of the cool water. She regarded the stranger in her mirror with disgust. The ravaged woman appeared distraught. Her makeup was a mess. Her eyes drifted to a red vase she’d placed on the corner of the vanity. It became a vessel for the anger she could no longer contain. She grabbed it from the counter and hurled it at the mirror. Her reflection disappeared in an explosion that sounded like a shotgun blast. Mirror shards scattered and sharp pieces of her reflected sadness now seemed to cover the cold ceramic tile, but the vase bounced. It remained uncracked and intact.

Rex McBroom finally stirred. “What’s going on?”

“If you’d wake up then maybe you would know!” McBroom shouted. Then she strode across the living room, grabbed her purse, left the house, and drove away. McBroom stormed off to her friend’s house and asked to stay the night, making up some excuse. But she couldn’t sleep. Early the next morning, she still felt too shaken to go home.

She climbed back in her SUV and called her mother, Mary Ann Schopp. “Something terrible happened at work,” McBroom said into the phone. Without thinking about it, McBroom already had begun to drive to her mother’s bungalow in El Lago, a quiet neighborhood tucked behind Houston’s NASA Space Center. Her visit was entirely unexpected. McBroom was supposed to be meeting her mother later that Saturday to celebrate her youngest son’s thirteenth birthday. Instead, McBroom was now cancelling her part in those party plans.

“I’ll need you to take over for me,” McBroom told her mother, using the same businesslike tone she normally reserved for her federal court job.

“I can handle that,” Schopp replied, then paused in surprise. Skipping Caleb’s birthday party was totally out of sync with her daughter’s supermom style. McBroom had raised three children, but Caleb, the baby, was the only one left at home. Still, Schopp knew not to ask questions. Pretty much everything that happened with her daughter’s job at the federal courthouse was top secret.

Minutes later, McBroom pulled her silver Nissan Murano into the driveway. McBroom, then forty-eight, was a native Texan and normally meticulous about her appearance. She rarely appeared anywhere without her hair carefully coiffed and her makeup neatly applied, but now she got out of the SUV looking spent and wearing borrowed jogging shorts and a wrinkled T-shirt. As she stepped through the back door into her mother’s neat kitchen, she fell silent and fought back tears. Her mother pulled her into their usual hug and McBroom mumbled, “I could not pretend to enjoy myself at the birthday party.” She knew (but did not say) that her insightful youngest son, a straight-talking middle school student, would ask questions she felt unprepared to answer. Why had she left work so early? Why had she argued with his father and fled?

McBroom’s mother fetched cups of coffee and they sat together at the tiny wooden table. Rays of sunlight streaming in the kitchen window failed to lighten the mood. Schopp could only guess this unexpected crisis must have something to do with that white-haired giant of a judge, the domineering man who’d styled himself as king of the Galveston federal courthouse.

For nearly five years, McBroom had served US District Judge Samuel Bristow Kent. Kent was part of the powerful network of federal jurists whose lifetime appointments were guaranteed by the Constitution. Cathy McBroom was part of a vast national court bu reaucracy of people who served at the pleasure of such judges. Initially, McBroom had raved about her “dream job,” which provided the financial stability she’d craved and a federal salary of more than $70,000 plus benefits. Later there had been trouble with the judge, though McBroom had explained to her mother that she, like all federal court employees, was bound by an oath to respect court confidentiality. She and other employees were subject to a strict code of conduct and generally never discussed the inner workings of the court or any judge’s behind-the-scenes behavior.

Whatever Kent had done, it had been bad, Schopp knew. Her eldest child had always been a steady, strong woman on whom Schopp herself had leaned when her first marriage fell apart and she’d divorced McBroom’s father. But this morning all of her daughter’s self- confidence and control appeared cracked, if not shattered.

McBroom kept repeating in a monotone that she couldn’t discuss anything.

“If you can’t talk about it, you’ve got to get it out,” Schopp insisted. “Go use the computer in my studio. Type down every little incident you can remember.”

Schopp wasn’t sure she should leave her anguished daughter behind, but birthday duty called. She drove off to fetch her grandson and ferried a carload of gangly adolescents with floppy hair and feet too big for the rest of their growing bodies to Clear Lake’s AMF Alpha Lanes, the bowling alley where the usual cake, Cokes, and souvenir ten-pin awaited. She invented excuses when her grandson asked about his missing mom.

Alone in the snug yellow-brick house, McBroom felt marginally safer surrounded by the comfortable clutter of her mother and stepfather’s blended lives, their cobbled-together furniture, aging housecats, and many memories of family gatherings and home-cooked meals. This was not McBroom’s childhood home, but it was a familiar place—her mother had purchased it more than twenty years before with Don, her mother’s second husband. McBroom had grown up in the industrialized Houston suburb of Channelview, where she had learned from her own dad, a tough chemical plant worker, to fight for herself as a girl, even when that meant using her fists to quiet a bully or walking away from the boyfriend who punched a hole in her parents’ garage wall. Today, though, she felt none of that strength.

McBroom shut herself up in the front bedroom that served as a combination office and a studio for her mother’s oil painting. Col-orful canvases filled with hand-painted roses and chrysanthemums surrounded McBroom as she stared into the void of the computer screen, digging deep inside to find words. Beside her in frames and on the wall of the hallway just outside the small room were images from other stages of her life. McBroom as a chubby toddler with her hair pulled back in a ponytail; McBroom smiling in a crowded gathering at her grandmother’s ninetieth birthday; formal portraits of the two children, Evelyn, and Casey, whom she’d had after marrying her childhood sweetheart; and a party picture of McBroom in a glittery black dress and holding hands with her second husband, Rex, the father of her son Caleb, whose birthday party she was missing.

Mostly she’d been a good mother. Her children knew she had their backs. And she’d often acted as the fixer for her parents and her younger brother, too, providing the glue that held the family together or, when that proved impossible, providing comfort when things fell apart. Along the way, she’d built a solid career as an experienced assistant in the cutthroat legal profession in lawyers’ offices and later attained an important post in the federal district court clerk’s office, workplaces that in the 1990s and 2000s remained largely male-dominated worlds tinged with sexism. In her forties, she’d be- gun to run marathons and completed five races in one memorable year. She normally buzzed with energy. But she’d never faced anything as difficult as this self-appointed task.

McBroom had decided to denounce a powerful federal judge. And she would do this alone. She knew her written words, once shared, would make an enemy of a jurist who’d earned a national reputation among law professors as a bully, and who had repeatedly proved himself capable of humiliating, harassing, and harming the careers of anyone who crossed him. This man had both an extraordinarily domineering personality and the formidable power of the robe he wore.

McBroom had never known any woman personally who had taken on a federal jurist for sexual misconduct except what she’d read and seen about Anita Hill. Back in 1991, McBroom and many other American women had been outraged and inspired as they watched the University of Oklahoma law professor testify before an all-male US Senate Judicial Committee about how Clarence Thomas, then a federal judge and US Supreme Court nominee, had sexually harassed her in his years as her boss in two different federal govern-ment jobs. Hill had worked for Thomas both in the Office of Civil Rights at the US Department of Education and again when he became chair of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, the federal agency that supposedly specializes in helping people who struggle with on-the-job harassment and discrimination. The experience hadn’t turned out so well for Hill, McBroom knew. Thomas had won a seat on the Supreme Court anyway. Hill had been branded as a liar by conservative commentators and ridiculed for testifying about how Thomas asked her about pubic hair on a Coke can and described scenes in porn films featuring large-breasted women having sex with men and animals.

McBroom still felt physically sick when she recalled what had happened to her that Friday inside Kent’s wood-paneled chambers—a formal yet intimate space that smelled of the judge’s illicit cigar breaks, his collection of law books, and his bulldogs. She feared that her decision to flee meant that he would seek revenge and ruin her career.

Events

11/2/2021: Booksmith—Bad Judges, Fact and Fiction via Zoom with attorney and author Lara Bazelon

11/12/2021: Politics and Prose via Zoom with NPR’s Carrie Johnson