Redistricting-palooza

The state of Texas is currently tied up in two legal challenges seeking to prove that newly drawn congressional districts leave minorities no more voting power than they had in the early 1990s. That’s despite the fact that minority populations are responsible for 89 percent of the state’s growth during the past decade. Districts are redrawn whenever the U.S. Census Bureau figures come in. It’s always contentious, and both political parties try to draw districts to their advantage. Yet when Republicans are in charge, minorities seem to get screwed.

In this latest instance, Latinos earned Texas four new U.S. House seats and still somehow got the shaft.

One suit in a San Antonio district court was brought by a long list of minority advocacy groups, as well as Travis County, the City of Austin, and several politicians. They charge that new district maps drawn by the Legislature discriminate against minority voters.

A second case in Washington, D.C., was filed by the State of Texas to get pre-clearance of its redistricting maps under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, the Voting Rights Act prevents minority communities from being divided and diluted. Due to a history of discrimination against minorities, Texas and eight other states—all Southern with the exception of Alaska—are required by federal law to get federal approval of any changes to their voting procedures.

Several minority-interest groups have also intervened in the D.C. case.

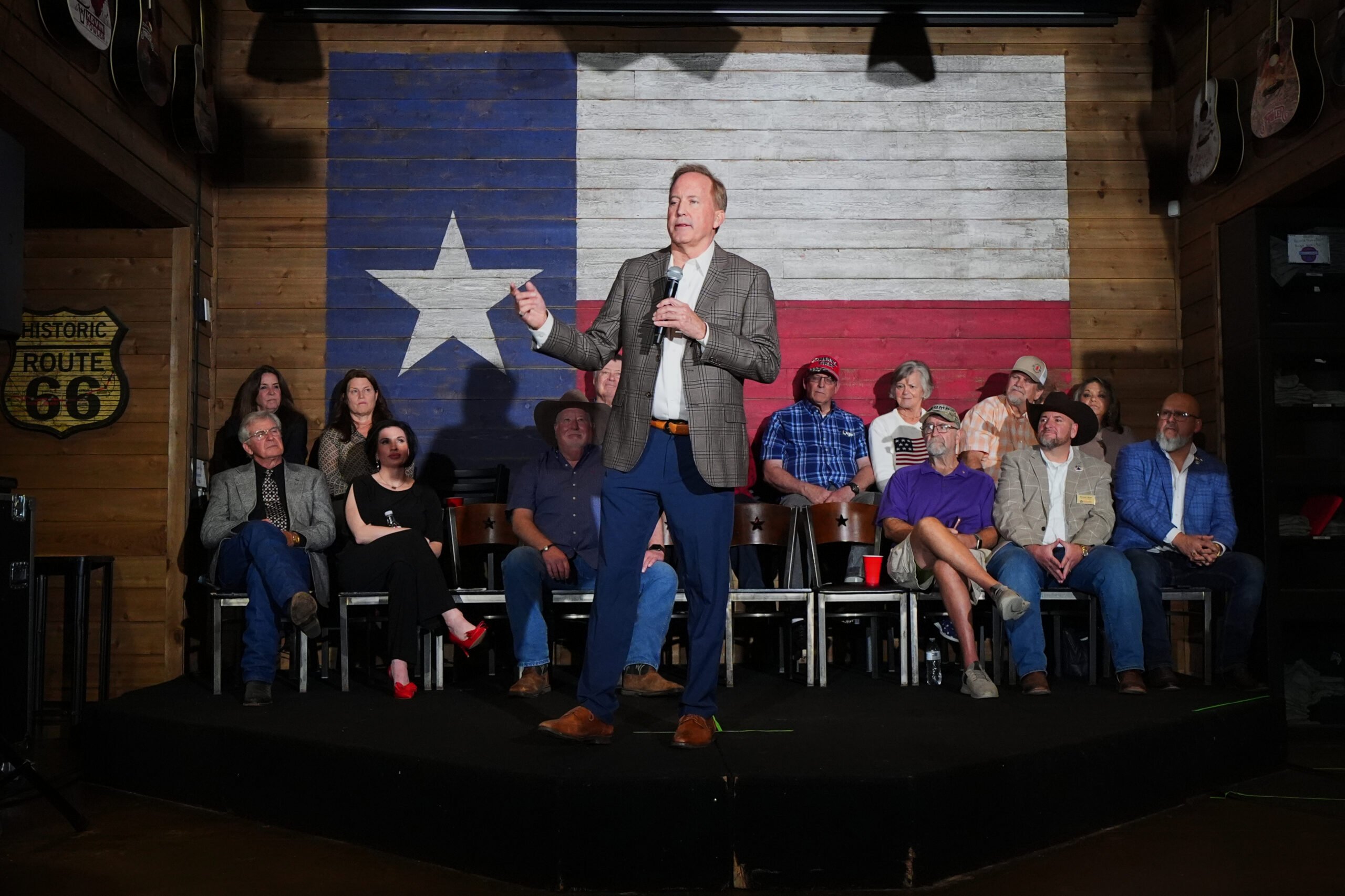

Deputy Texas Attorney General David Schenck, defending the maps before a panel of three federal judges in San Antonio on Sept. 6, argued that the new districts don’t drain power from people of color. “Whites are voting for and electing African-American and Latino candidates at record levels,” Schenck told the judges. “[The candidates] just happen to be Republicans.”

Of course, when it comes to this country, “record levels” still amount to scraps. (How many female presidents have we had again? And would we still want one if she’s Michele Bachmann?) Especially when you consider that none of this redistricting would be happening if it weren’t for the four new congressional seats Texas earned due to Hispanic growth recorded in the 2010 census.

“From almost five million population growth, 90 percent was due to minorities and 66 percent of this growth was Latino; the remaining was black and others. Yet we didn’t get a single congressional district,” said Brent Wilkes, National Executive Director of LULAC, during a meeting with the Department of Justice on Sept. 1.

The new maps create no new minority districts, but they do have one “minority-opportunity” district in which Latinos could partner with other voters to elect their candidate of choice. That’s District 35, which includes Bexar County, a largely Hispanic, largely Democratic population. The district was drawn, however, to oust Austin congressman and Democratic lion Lloyd Doggett.

The big clue that gerrymandering is going on can be found in the awkward appendages on some of the newly drawn districts. Dr. Morgan Kousser, professor of history and political science at the California Institute of Technology and an expert witness for the Mexican-American Legislative Caucus, testified in San Antonio on Sept. 6 that appendages like the one on Congressional District 26, which dips down from Denton County into Tarrant County, almost splitting Congressional District 12 in half, are red flags.

That appendage is 71 percent minority, Kousser said, but when it’s included with Denton County, those minorities get diluted by a 61.9 percent Anglo, and largely Republican, county.

University of Texas law professor Steve Bickerstaff, author of Lines in the Sand, about the 2003 congressional redistricting controversy, said he thought the Department of Justice would object to the new maps. Bickerstaff was right. On Sept. 19, the Justice Department announced it wouldn’t pre-clear the new map. If no easy fix emerges from the San Antonio court, Texas will try the suit in D.C.

If all else fails, the state could go to the U.S. Supreme Court to challenge the constitutionality of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, knowing that the conservative court may be open to that argument.

A possible court challenge to the Voting Rights Act presents a dilemma for opponents of the plan and for minority voters who are facing the brunt of the conservative party’s last-ditch effort to keep control of a changing Texas.