Wendy Davis’ Media Fail

The campaign’s mismanagement of the press is damaging Davis' candidacy.

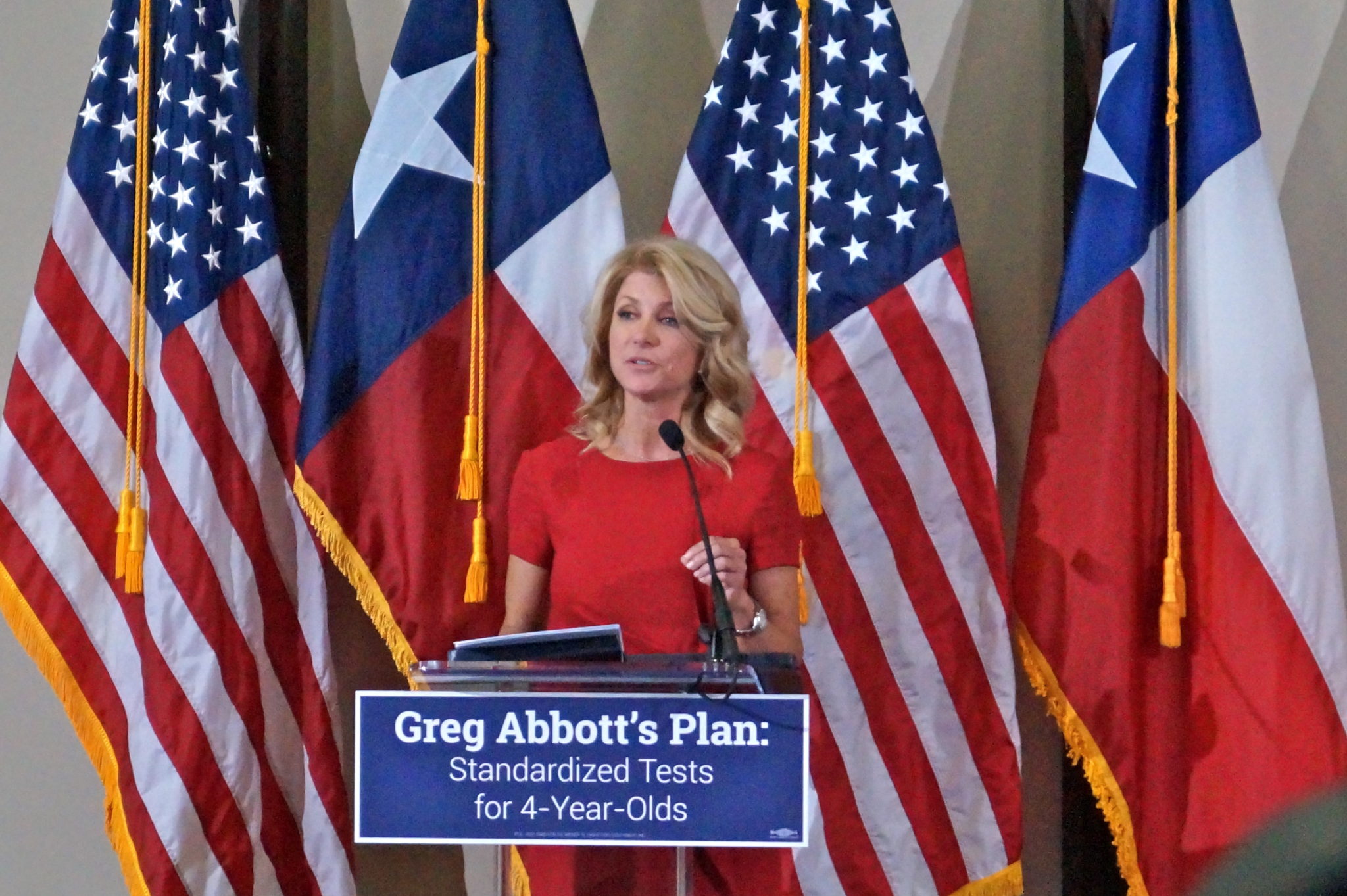

Above: Wendy Davis speaks at her gubernatorial campaign announcement October 3 in Haltom City.

I’ll concede here at the beginning that I’ve never worked on a political campaign. Nor do I have any experience in media relations, publicity, political communication or whatever else flacks do. I don’t know the nuances of trying to defuse controversy with a speech. But I have covered many political campaigns in Texas the past decade, so I know what it looks like when a campaign handles the press well.

And the Wendy Davis operation is about the worst at media relations that I’ve ever seen. Her team’s mismanagement of the press is damaging her candidacy.

The foul-ups began as soon as Davis entered the race, and hired a young and relatively inexperienced communications team that had spent little to no time working as reporters. At first, the mistakes were minor, even funny. For instance, Davis’ press staff directed a Texas Tribune reporter to the wrong place for an event and gave a Texas Observer reporter the wrong address to their own campaign headquarters. I’m sure that was annoying for the misdirected reporters, but nothing that would affect the campaign.

As the weeks went by, though, Davis’ team often treated the press with suspicion, asking repeatedly what a story would say before granting access to staffers, refusing to confirm basic campaign scheduling details and shielding Davis from in-person interviews with some major outlets.

That won’t win you any friends in the press and won’t earn much favorable coverage. Still, these are the kind of errors that only journalists care about, the stuff of endless reporter gripe sessions.

In November, when Davis swung through the Rio Grande Valley, the mishandling of the press started to become a real liability. The campaign invited reporters to attend volunteer phone-banks. That’s not the most compelling political theater, but reporters in the Valley showed up for a rare chance to query Davis in person. At the event in McAllen, as the Monitor’s Sandra Sanchez would later report in a piece titled “Wendy Davis Is Not Ready for Prime Time”:

“It was embarrassing to watch as a campaign staffer prematurely announced Davis’ arrival and urged everyone to stand up and chant, which they did for several minutes until it was obvious that Davis wasn’t there. ‘I thought she was here,’ a worker mused into the microphone to the quizzical and confused glances from the crowd of 60 or so.”

When Davis did arrive, she met with reporters for 10 minutes. Sanchez asked the candidate about her statement, at an earlier event in the Valley, that Davis was “pro-life.” This was a predictable question given the campaign’s reluctance to even say the word “abortion.” Sanchez documents what happened next: “[Davis] looked at me and shook her head. But before she could articulate, her new press aide Rebecca Acuña jumped in and said ‘that comment was taken out of context.’”

You almost never see a flack jump in front of their boss like that. Makes the politician look weak. Acuña then called Sanchez later that night and asked her to change a headline on the Monitor’s website.

We might blame these screw-ups on the follies common to a recently formed campaign. But it’s gotten only worse.

In the past two weeks, the campaign’s response to the controversy over the details of Davis’ bio (aka, Trailer-gate) has been slow and weak. On Tuesday night—a mere 11 days after The Dallas Morning News story that raised questions about her bio was published—Davis gave what her campaign termed a major speech to “set the record straight” at a fundraiser in Austin.

That quote—“set the record straight”—comes from the media advisory about the speech the Davis campaign distributed on Tuesday afternoon. A media advisory is like an invitation. By sending one out, you’re inviting (or in some cases begging) the press to cover your event.

But when reporters arrived at the Four Seasons ballroom, they were turned away. As The Dallas Morning News’ Wayne Slater and the San Antonio Express-News’ David Saleh Rauf reported, event organizers said the room was too full and there wasn’t space for the press. Why wouldn’t they make room for media at an event that featured Cecile Richards, head of Planned Parenthood, and Davis’ response to a controversy attracting national media attention?

Of course, there was room for some media—The Texas Tribune was allowed in to livestream and cover the speech. That, according to a well-reported piece by the Statesman’s Jonathan Tilove, was the result of intrepid work by Tribune reporter Jay Root. Good on him for getting a scoop. But that doesn’t explain why the campaign and event organizers would grant exclusive access to a major campaign speech to one media outlet.

It turned out the Davis campaign’s media advisory actually stated that the event was closed to the press but helpfully provided the link to the Trib’s livestream. This is not unlike someone sending you an invitation that says you’re not invited to a party, but, hey, you can watch it on Skype.

If you would find that offensive, then you can understand why some reporters, Rauf especially, were angry and have been ripping the Davis campaign and the Democratic Party this week on Twitter.

While it’s not smart to enrage most of the Capitol press corps, there’s a bigger issue. The Davis campaign almost certainly robbed the speech of wider media exposure by barring TV stations and major daily newspaper reporters.

Then there’s the questionable decision to hold Davis’ big “set the record straight” speech, after not responding very forcefully for 11 days, the same night as the State of the Union.

That’s all too bad, because Davis gave a great speech. It was heartfelt and impassioned. You can watch it on YouTube. It’s been viewed 801 times.

The gubernatorial campaign has just started, of course, and there’s plenty of time for the Davis staffers to become more media savvy. But so far their handling of the press is doing a disservice to their candidate.