To Kill? Or Not to Kill?

As executions decline in Texas, a small-town prosecutor decides whether to seek the death penalty.

A version of this story ran in the May 2014 issue.

Above: Matagorda County District Attorney Steven Reis outside the courthouse in Bay City.

One morning in August 2011, Matagorda County District Attorney Steven Reis drove out to a crime scene at a remote, secluded farmhouse. A 78-year-old man named Glen Sam Prinzing had been found dead at his property on the edge of Markham, a town of a thousand residents 30 miles from the Gulf of Mexico and about 90 miles southwest of Houston.

The barn was several hundred yards off the main road. Reis drove with sheriff’s deputies over a bumpy dirt path, across an empty field, and past where yellow police tape cut through thick brush. It was a hot, sticky day, and Reis saw that the vegetation had tangled over all manner of rusting old junk: cars, a tractor, a refrigerator. They crossed a plank of wood placed as a makeshift walkway over a pool of muddy water. Reis, wandering into the farmhouse, saw several vintage motorcycles, some dating to World War II. They had mostly fallen into disrepair. The word “hoarder” came to mind.

Known to his friends as Sammy, Prinzing was a reclusive collector and avid Bible reader keeping up his family’s old rice farm. The day before, a neighbor had realized he hadn’t seen Sammy in several days and walked over to the farmhouse, where he found the body. At Prinzing’s age, natural causes would have been a plausible theory, but there was no doubt that something else was responsible: Prinzing’s head showed signs of blunt force trauma. Someone had beaten him to death.

Reis was called because he prosecutes murder cases in this area of southeast Texas, and he likes to see the crime scene firsthand. Seeing the scene helps him ask witnesses more informed questions if the case goes to trial. The sheriff’s deputies said that the motive appeared to be robbery. They deduced that someone had taken a metal rod and hit Prinzing in the head while he lay sleeping and then made off with some of the farm’s more valuable items. If that conjecture proved correct, the death penalty—eligible only for defendants who commit murder in conjunction with another crime such as robbery or sexual assault—would be an option.

But who even knew that Prinzing, living on his remote farm, had items to steal? The murder of a man with few friends and fewer enemies left little for law enforcement to investigate. Over the next few weeks, local deputies, Texas Rangers and Department of Public Safety investigators looked for clues and chased down leads. They found bloody fingerprints on the barn door but couldn’t match them to anyone. After a while, the case went cold.

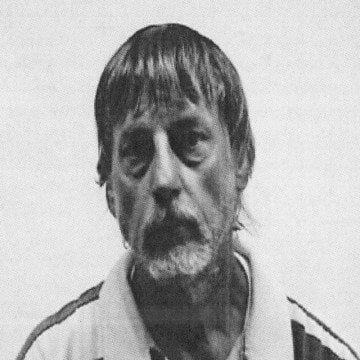

Nearly two years later, in July 2013, a drifter named Robert Kotlar, while strung out on drugs, admitted to an acquaintance—who would become an anonymous tipster—that the authorities might be looking for him because he and two accomplices had broken into a farmhouse several years before and killed its owner. Kotlar was arrested for a parole violation at his home in El Campo, about 25 miles from Markham. His fingerprints matched the ones found on Prinzing’s barn door.

By then, Kotlar had been put on the Department of Public Safety’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list, with $7,500 offered for tips on his whereabouts. He had been known to use the aliases “Murdock” and “Paul Wayne Conners,” and had previously been arrested for assault, burglary, larceny, theft, forgery, drug possession, resisting an officer and giving an officer false information. According to the Most Wanted listing, he had multiple tattoos, including several skulls on his right arm and the back of his left hand, and “should be considered ARMED and DANGEROUS!”

Kotlar and his accomplices—one was already in jail in Austin for an unrelated crime, the other was found living quietly in Matagorda County—were appointed attorneys and locked into cells at the Matagorda County Jail. Kotlar was believed to be the one responsible for the blunt force trauma to the head that caused Prinzing’s death.

It was Matagorda County’s first potential death penalty case in years. If it did become a capital murder case, a jury would have to decide whether Kotlar should be sentenced to death. It would then be up to state and federal appeals courts to uphold the verdict, and the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to carry out the execution by lethal injection.

But whether to seek the death penalty, whether it was even on the table, was Steven Reis’ decision alone.

The death penalty is declining all over the United States, and especially in Texas, the state most famous for capital punishment. The statistics are startling: Texas sent nine men to death row in 2013, down from 48 in 1999. The lengthy appeals process in capital cases—offenders spend on average about a decade on death row before execution—means it takes a long time for the number of new death sentences to influence the number of executions. Still, executions are declining too. Between 2010 and 2013 there were 61 executions in Texas. Between 2000 and 2003, there were 114.

Explanations for the death penalty’s decline run from culture to policy and back again. Violent crime overall has decreased in recent years. While a majority of Texans still support capital punishment, it’s become increasingly difficult for the state to win a death sentence and carry it out. In 2005, the Texas Legislature approved a new punishment: life without the possibility of parole. Where juries once had to decide between execution and a “life sentence” that might actually mean 40 years, now juries can spare a defendant’s life knowing he or she will never leave prison.

In the meantime, defense lawyers have become more skilled at utilizing “mitigation evidence,” or facts from a defendant’s background offered during a trial’s punishment phase, that can humanize the defendant and sway a jury toward leniency. Juries also may be reluctant to administer an irreversible death sentence after a number of high-profile exonerations of death row inmates across the country, including several in Texas. And a slow march of U.S. Supreme Court rulings barred the death penalty for certain classes of defendants (the young, the severely mentally impaired) and for certain crimes (rape).

The legal concerns are compounded by economics. Death sentences are tremendously expensive to prosecute, especially for small counties. They take months of preparation by the prosecution followed by weeks of courtroom time during which a county’s docket can become severely clogged. The appeals process stretches over years and demands hundreds of work hours. Striking a plea deal for life in prison instead of seeking the death penalty can preserve a small-county DA’s annual budget. This means that urban counties with larger budgets have an easier time seeking the death penalty. Last October, newspapers and magazines around the country covered a Death Penalty Information Center report showing that only 2 percent of counties—representing less than a quarter of the U.S. population—produced 56 percent of the nation’s death row inmates. “Prosecuting a death penalty case through a verdict in the trial court can cost the prosecution well over $1 million dollars,” the report quoted Boulder County, Colorado, DA Stan Garnett as saying. “My total operating budget for this office is $4.6 million and with that budget we prosecute 1,900 felonies, per year.”

Though cost is always an issue, no prosecutor will admit that the budget shapes decisions about specific cases. In Texas, if a particularly horrific murder takes place—if a police officer has been killed, or a young child raped and strangled—a prosecutor will likely still seek the death penalty.

In theory, anyway. In reality, every case is different, with its own details and context. And in all the talk of policy, what’s often left out is that it’s the district attorney alone who takes the details and that context and decides whether to pursue the death penalty.

In a big urban Texas county, the district attorney makes this decision multiple times every year, often with the help of a committee. He or she probably doesn’t know much about the defendant or the victim other than what has been gleaned by investigators. But in sparsely populated counties like Matagorda, the DA might personally know the victim, the murderer, or family members or friends of each. In every kind of case, from drunk driving all the way up to capital murder, Steven Reis sees the people affected by his decisions at Little League baseball games and at the grocery store. Parolees and probationers have ridden their bikes by his house.

Of a DA’s many decisions, few are more career-defining than whether to seek the death penalty in a capital murder case. People will remember it, and people will criticize it. By the time Prinzing was beaten to death, Reis had confronted the death penalty decision twice. In each case, there were myriad factors—political, legal, and personal—to consider, but they all condensed into a simple yes or no. “You consult with the victim’s family, you talk to others in your office,” former Bell County District Attorney Arthur Eads said in a 2011 oral history for the Texas After Violence Project, “to get the power of their advice; how do they feel about it?

“Then you have to go off, and you’ve got to sit in the corner, and you’ve got to decide. And when you come out of that corner, buddy, it’s you versus everybody. There’s no surrender. I don’t care who you’re up against. I don’t care what town or city you live in. Let’s get it on.”

As Reis weighed whether Kotlar would face the death penalty for murdering Prinzing, I accompanied him one Friday this past January to the weekly luncheon of the Bay City Lion’s Club. Reis is the “3rd Vice President” of the local civic organization. We arrived late. The room was full of men in yellow vests. They sang “God Bless America” and recited the Pledge of Allegiance. Lunch was chicken-fried steak, cheesy potatoes and steamed vegetables brought out on ceramic pates. Reis was the only one without a yellow vest, dressed elegantly in a three-piece suit of houndstooth and stripes, a driver’s cap and a long black coat. He has thick white hair and a trim goatee. Though he had an easy, comfortable rapport with the other men, the formality of his dress was a reminder that he’s still an elected official.

Over lunch, Reis, who had just turned 60, told me about his early life, a circuitous one for a district attorney. He grew up in Matagorda County and studied journalism at Texas A&M University in College Station, working as a janitor on campus and, during the summers, as a deckhand on a tugboat. He married his high school sweetheart, and they have seven children. After a brief stint in the Air Force, he returned to Bay City and bought his father-in-law’s loan business. He obtained a degree in counseling. He started an MBA program and dropped out. Then he worked in real estate before the market bottomed out.

He had always thought about becoming a lawyer. He was still in his early 30s, but his wife told him that if he wanted to do law school, he’d have to do it now or wait until their youngest child turned 18 (which didn’t happen until this year). So he went to law school in Houston, commuting home every weekend to see his wife, who he says was running “the [real estate] business I was basically abandoning.” He became a lawyer in 1989, at age 35, and practiced solo for a couple years before the county attorney asked him to take a job as a prosecutor and he accepted.

In 1991, scandal struck the county when a probation officer was raped at a party attended by many of the community’s most powerful people. A complicated controversy, which included an investigation by the Texas Attorney General’s Office, swept out many of the county’s public officials. As the election for district attorney loomed, Reis found many of his colleagues encouraging him to run. He hated campaigning, but still managed to win. He wasn’t young, but he wasn’t experienced either. He had never won a jury trial in his life.

After taking office, Reis realized he would enjoy the job only if he could temper the explosive emotional conflicts that often accompany criminal trials. He’d had one awful experience as an assistant county attorney when an adversary had screamed in his face, nearly spilling Reis’ coffee all over both of them. “Maybe law is not where I need to be,” Reis remembered thinking. “I’m losing cases. I’m being yelled at. I’m expected to be mean to people.”

But as district attorney, Reis could set the tone. He told defense lawyers he never wanted a case to become so “rancorous” that they couldn’t later go out for a meal together—or run into each other at the Lion’s Club.

In 1998, Reis was called out to a grisly crime scene not far from his courthouse office in Bay City. A young woman named Linda Malek had been found lying face-down in her bedroom, with much of her jewelry and her purse missing. Her 8-year-old daughter, Ashley, told investigators she had seen two strange men enter the house. She’d seen them order everyone on the ground. She’d seen them ask about where the jewelry was kept. Then she’d seen them rape her mother. Her mother grabbed her hand. “She was squeezing it so tight it hurt,” Ashley later said on the witness stand. “Mommy was begging them not to shoot her … and they shot her twice.”

The two men asked Ashley where her mother kept the car keys. They took them and left, returning several minutes later to ask the girl how to start the car. She told them to push in the clutch.

Early the next morning, the girlfriend of a man named Kenneth Parr found the victim’s purse in her trash. Michael Jimenez, Parr’s brother, was holding a box of jewelry. “We were going to kill the kids,” Jimenez told her, as she later testified, “but the gun messed up.”

There wouldn’t be a pitched battle at trial over guilt. “There was a mountain of evidence against him,” recalled Parr’s attorney, Mark Racer, which included a full confession and evidence that Jimenez had written a rap song about the murder. The real question was whether the brothers would face the death penalty. Jimenez, 16 at the time of the crime, was too young. Reis had him certified to stand trial as an adult to face life in prison. Parr was 18, and Reis saw him as more culpable. So the prosecutor decided that a jury should be given the option of sentencing Parr to death.

Few disagreed, especially in law enforcement circles. Malek’s boyfriend and father worked for the sheriff’s department. Malek’s mother, Charlotte Brown, who had gotten the first call from Ashley and had seen her daughter’s body, had recently been hired by Reis’ office. Reis maintains that the decision to seek death in Parr’s case was independent of his relationship with the victim’s family. But he acknowledged that he felt tremendous pressure to deliver the death sentence. “It’s horrible to think back on the pressure,” he told me.

Reis’ personal relationships also extended to the defendant’s side. When Reis had worked in real estate, Parr’s mother, Mary Saldierna, had rented an apartment from him. “She knew me as a landlord who had probably not made her pay the rent when she couldn’t,” he told me. “She paid what she could pay, and I let her live there. And so when I called her as a witness to testify against the son I was trying to kill, that was hard on her. That was hard on me.”

After Parr was found guilty of murder, the jury heard arguments in the punishment phase over whether he should be sentenced to death. Parr’s mother took the stand, and her son’s attorney, Stan McGee, tried to weave a narrative in which Parr had little structure growing up. His mother had spent a couple of years in prison when Parr was in middle school, and he’d been in foster care. He’d witnessed her relationships with a string of men. McGee implied that Parr’s mother was a weak parent, unable to show her son right and wrong. She pushed back. “They weren’t mistreated,” she said. “They had a house over their head. They were being fed.”

Reis followed with a cross-examination in which he tried to prove the opposite: a loving mother whose son had no adequate excuse for his crime. The DA who took office having never won a trial proved a shrewd courtroom litigator in turning a mother’s testimony against her son. “You said that you tried to teach your children to learn some responsibility?” Reis asked, suggesting that Parr could not blame his actions on a bad childhood. “Yes,” she responded. “I’ve talked to them about being responsible. I’ve talked to them about … making something out of theirselves.”

“After her testimony,” Reis remembered, “I went over and said, ‘I’m so sorry.’ She cried, I cried with her. She certainly didn’t want me to kill her son.”

Donate now to support independent, nonprofit journalism.

He succeeded. The jury sentenced Parr to death. He spent years on death row. As the execution date neared, Reis asked the victim’s mother if she would allow him to witness the execution. It’s not common practice for prosecutors to watch executions, but Reis wanted to test his own reaction. He wanted to see the process through to the end. “The question I asked myself was, ‘Would you do it yourself? Would you stick the needle in the man’s arm? Would you put the gun to his head yourself?’

“Because let’s not mince words, let’s not play games. We’re killing a human being. Would you look him in the eye? Would you blow his brains out and watch him die? That has to be the visceral picture of what you’re doing. Can you cold-bloodedly kill this human being? If you cannot, why would you ask 12 people to make an executioner do that?”

Actual executions in Texas are not so gruesome. They are quiet, even routine procedures. On a Wednesday in August 2007, eight years after the trial, Reis learned that he had been added to the witness list. He drove up to Huntsville, where he met Charlotte Brown, his former employee and the victim’s mother. Together with other family members, they were escorted into the execution chamber’s small viewing room, across the glass from the gurney. On the other side of a thin wall were Parr’s family members, including Reis’ former tenant, but he couldn’t see them.

In the days leading up to the execution, Parr had reportedly threatened to rape female prison employees. Talking to an Associated Press reporter, Reis projected confidence, citing one of the crime’s more horrific details: the fact that Parr and his brother almost shot the victim’s two children. “I thank God for having intervened by causing a rifle to jam,” Reis said, “before those two murderers could kill two helpless children.”

The curtain opened. Reis was thinking about God as he saw Parr—now calm—through the glass, with a needle in his arm. He wondered where Parr would go when he died. “My job results in his death,” Reis remembered thinking. “My job does not result in his damnation. That’s between him and his creator.”

Several people in the witness room were chatting, and Reis silently stepped as close as possible to the glass. “I’m looking and watching his eyes and hoping and waiting for some sign that he’s made peace with God, or whatever his faith is.”

He could hear Parr’s mother crying in the next room. Then he heard Parr through a small speaker connected to a microphone hanging above the gurney. “Can y’all hear me?” Parr said. “Tell my family that I love y’all. … Keep your head up. I love you.”

There would be no apology or remorse, but still Reis looked for some sign of spiritual redemption. The drugs started to flow, and Parr closed his eyes. His mother wailed and banged on the glass. Reis stood silently as nine slow minutes passed. He wasn’t sure what he was looking for, exactly, but he kept his eyes on the gurney.

“I watched,” Reis said quietly, “and I didn’t see anything. … Nothing. I saw him die.”

Reis shuffled out with other witnesses. He saw Parr’s mother but didn’t make eye contact. After driving home, he called his preacher, and they met in the courthouse office. “I broke down and started crying,” Reis said. It wasn’t because he’d been partially responsible for Parr’s death. It was because he wasn’t sure Parr “made peace” before he died.

But he had answered the question he had gone in with: Could he seek the death penalty again? “I confirmed for myself that yes, I wasn’t deluding myself, that I would be willing to do what needs to be done,” he said. “It confirmed for me that I wasn’t lying to myself.”

Shortly before Parr’s execution, Reis had started to consider a second potential death penalty case. A man named Francisco Castellano was being held in the Matagorda County jail. He had described to officers how his brother-in-law started complaining of pain and went to the hospital with the rest of their family members. Castellano was left to take care of three young children, including a 4-year-old niece. He said he’d picked her up, accidentally injured her genitals, and then dropped her. Then he took her outside. “I continued hitting her on the floor with her head,” he said, through a translator (he spoke little English). “I don’t know what came over me to grab a knife. … And I stuck the knife in her … in the chest … and then on the left side of the neck.”

Castellano had told the girl’s mother—his sister—that the girl had disappeared. He then helped search for her, knowing all along that he had raped and killed her, and where her body was. Reis got a queasy look on his face remembering the story, and seemed more uncomfortable than he had been while discussing Parr’s murder. He had visited this crime scene as well. “I can still see her body laying in the weeds,” he said.

Reis decided that if he sought the death penalty, he would probably get it. But it wouldn’t be a simple task. Castellano’s IQ was right around the line of what might be considered intellectual disability. In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court had decided that executing those with “mental retardation” would be “cruel and unusual punishment.” Even if Reis convinced the judge and the jury that Castellano was culpable for the crime, a future appeals court might decide that he was ineligible for the death penalty.

In addition, Castellano was a Mexican national. Reis wanted to investigate Castellano’s youth to see if he had a violent past, and he’d need to go to Mexico to do it. But he’d been warned that it might not be safe to go to Castellano’s hometown if people discovered his intentions.

James Stafford, Castellano’s defense attorney, did investigate in Mexico. He brought Reis details from his client’s life that would likely be brought in front of a jury in a plea for mercy. “The childhood was just so bad,” Stafford recalled. “It would be hard for an American to appreciate the extreme poverty he was raised in. They had dirt floors. The mom was working in a whorehouse and she’d take him with her. He witnessed his mom’s sexual activities. And some of the johns messed around with him when he was 9 or 10. All of his sisters were prostitutes. And his mom was a devil worshipper with voodoo dolls. It just went on and on.”

On the other side, Reis knew that plenty of his own employees wanted him to seek death. Stafford told me that Reis’ assistant district attorney, Carla Post, “was definitely the driving force” on the pro-death side. (Post, who has since gone into private practice, said she wouldn’t comment without revisiting the case record.)

The trial was approaching, and death was still an option. Stafford, along with a team of other lawyers, started preparing the defense, arranging for Mexican witnesses to testify about Castellano’s upbringing. Reis prepared for a court battle in which he would describe to the jury the image of the girl’s body lying in the weeds.

But then, as Stafford tells it, Castellano’s family members started to weigh in, telling Reis that despite their grief over the little girl’s murder, they didn’t want Castellano executed. Reis remembers that some family members wanted a death sentence, but he started to realize that even if he succeeded, it was likely that Castellano’s mental issues would come back on appeal, perhaps leading to a second trial. “I wanted finality for them,” Reis told me, noting that many of the family members were undocumented and might face cross-examinations in which their immigration status would be challenged. “How do you put people through that and still call the end result justice?”

Stafford took Reis’ doubt and bargained: Castellano would plead guilty to a host of charges other than capital murder, including three counts of sexual assault, so that he’d be sentenced to prison for the rest of his life. There wouldn’t be a trial—just a quick plea hearing, and Castellano would head to prison for good. Reis agreed. He still stands behind his call but admits that “there were plenty of people who think I made the wrong decision.” Those people felt that Reis shouldn’t have robbed a jury of the ability to decide Castellano’s punishment.

And Reis indulged that line of reasoning. “What makes me think that I’m God and can take that decision away from somebody?” he said, summarizing what might go through a juror’s mind. “One elected guy, who never won a jury trial ever, who has a history of working as a deckhand on a tugboat, a janitor, a reporter, a loan shark, who is a failure at real estate, who finally becomes a lawyer and doesn’t like it, becomes a prosecutor and doesn’t win a case, and he’s going to decide whether I get to kill this guy? Who the hell is he?”

Reis was not thinking about statistical curves when he said yes for Parr and no for Castellano. Because each case is its own bundle of strategic and moral particulars, it doesn’t really make sense to point to the fact that the year Parr was sentenced to death, 47 others around Texas joined him, while the year Castellano got life in prison, the number of Texas death sentences was only 12. And yet Castellano’s case did fit into some larger trends, including the decreasing willingness of courts to allow the execution of the mentally disabled. So it’s not unreasonable to think about these two decisions as a part of trends that extend beyond Matagorda County.

With the number of death sentences now so low, the decision in Kotlar’s case would have a significant impact on Texas’ total statistics, but it would add to the state’s total for the year only if Reis said yes. And there isn’t a good statistical way to measure all the factors he was considering, a way to measure the lofty terms Reis uses when talking about the case, like “justice” and “fairness.” Yet, in death penalty cases, it’s also easy to get lost in the details. In Kotlar’s case, the details had emerged from law enforcement interviews with Kotlar and his two co-defendants, Christopher Evans and Michael Allen Horton Sr., and formed the outline of a riveting narrative that Reis could present to a jury.

Since the men were charged in sealed indictments, Reis couldn’t tell me much about those details, but James Stafford, who represented Castellano and is now representing Evans, has seen the statements videotaped by the Texas Rangers investigating the murder. What we know is that the three met at Barton Springs pool in Austin. Kotlar had always been a drifter, in and out of prison and various jobs. He’d happened upon Prinzing’s house several years before and seen all those motorcycles, which he figured must be worth something. “They thought they could make a lot of money,” Stafford told me.

The three men stole a rowboat in Austin and set off down the Colorado River, which winds through Matagorda County on its way to the Gulf. They used brooms to paddle until they came upon a weekend home, which they broke into and stole some items, exchanging them for cash to buy oars.

Eventually they arrived in Columbus, 90 miles southeast of Austin, where they ditched the boat. Kotlar found them a ride to Bay City, and they then made their way to Prinzing’s property in Markham. As the men entered the farmhouse, Kotlar found a piece of pipe stuck in the ground. He grabbed the pipe and used it to kill Prinzing.

Texas law would allow the death penalty for all three men, but Reis would have to prove to a jury that Kotlar’s accomplices reasonably expected him to kill Prinzing. Since the victim was sleeping and Kotlar didn’t arrive with a weapon, that would be difficult. “What did my client know when they went to steal the motorcycles?” Stafford said of Evans, a homeless man from Austin. “Did he reasonably expect someone would die?”

From Reis’ position, the case is strategically complex, because he has three defendants with three lawyers and a mountain of evidence to deal with. Kotlar would be the most viable candidate for the death penalty.

Realistic, sure, but there are other factors to consider. Kotlar is 55, much older than Parr or Castellano had been when Reis tried them. If sentenced to death, Kotlar might die before he’s executed. The murder was cruel and cold-blooded, but it would be easy to think of other murders more cruel and more cold-blooded. Prinzing, the victim, lived alone, and doesn’t have multiple family members calling for vengeance.

On the other hand, there are plenty of indications that Kotlar, at his age, would not be easily painted with a redemption narrative by defense attorneys (Kotlar’s attorney declined to comment for this article.) He’s been on the Most Wanted Fugitives list. That the case was cold for so long made many in Matagorda County fearful, and that would work to Reis’ advantage as he picked a jury willing to choose death. “I’ve got this unsolved crime. A dead man, who everybody in this whole county knows,” Reis explained. “Everybody is afraid. Who killed him? We have a murderer running the streets. Everyone’s worried. They can’t sleep at night, because this old, helpless, never-bothered-anybody guy has been murdered, and we haven’t caught the bad guy.”

The picture of Prinzing as a vulnerable, kind-hearted old man who had done nothing to deserve his fate was bolstered by a letter to the editor in the Bay City Tribune. Sammy “would not kill or harm any living creature nor would he cut down a tree, unless it was absolutely necessary,” wrote his friend Louis Kopnicky. In an email to me, he added, “I believe in the death penalty and feel the murderer of Sammy should receive the DEATH penalty.”

But would a jury agree? And should they be given the option? When we spoke in January, Reis was still slowly going over the many documents, talking with his staff, doing all of the necessary legwork before going into the corner and coming out with a decision.

He admitted that whichever option he decided to take, it might be different from the decision another district attorney in another county would make. If he did not seek death, there would undoubtedly be members of the community who disagreed with his decision. As with Castellano, they would argue that a jury, and not just one man, should make the final decision on whether Kotlar lives or dies.

Several months later, Reis got in touch to tell me that he had made a decision. Reticent to speak off the cuff, he composed his thoughts in a 2,000-word email. He said that because the investigation of the crime and negotiations with the defense attorneys are still proceeding, he couldn’t discuss the details of the case. But for Kotlar, he wrote, the state would not seek the death penalty. He will spend the rest of his life in prison.

Since he could not reveal the details, Reis wrote on a more theoretical, even philosophical plane. “When we ask a jury of twelve people to return a verdict, which may result in the death penalty, we are asking our neighbors to make a decision they will live with for the rest of their lives,” he wrote. “In a death penalty case, I have no doubt jurors carry that memory with them for as long as they live. I don’t want them regretting their decision. Ever. They will always remember, as well, that their choice was made, in part, because I asked them to do so.”

He wrote about integrity, about the goal of “seeing that justice is done,” about his duties to jurors and defense lawyers and about the smallness of small towns. “In Matagorda County, if people disagree with my opinion, they don’t hesitate to let me know,” he wrote, “whether I’m eating at a local fast food restaurant, walking from the courthouse to my home, or leaving a church service.”

He wrote about the subjectivity of his decisions and the negotiations involved in plea bargains. He wrote that “sometimes we have a duty to check our own hearts and minds.” He wrote about asking his colleagues for advice and talking it through when they disagree.

“Justice is not done by one person,” he concluded. “It is done by a community acting in concert and with a sense of trust in one another and in the system. The prosecutor does not DO justice—that’s not the duty—it’s a prosecutor’s mandate to see that it IS done.

“I cannot tell you what will happen in these cases. But I can tell you I believe that the decision not to seek the death penalty will lead to a just result.”

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.