The Fight for Fair Housing

Two lawsuits are dragging Texas—and maybe the whole country—closer to the goal of integrated neighborhoods.

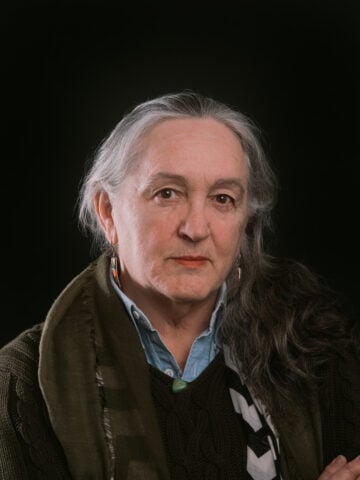

Above: Tamara Hodge-Robertson with her niece’s children, Kaisyn and Harmonye Pink, and Hodge-Robertson’s sons, Marlon Hudson, Ta’Mark Robertson and Lonzo Robertson outside their home in Frisco.

Tamara Robertson grew up in a rough part of Oak Cliff in Dallas, determined to get out. “I wanted more than a job at Jack in the Box,” she said.

She got a job at Southwestern Bell, started classes downtown at El Centro College, and moved to North Dallas. But in 1999 a difficult pregnancy derailed her job and her college plans. A few years later, she divorced her husband. He was “stuck,” she said—stuck in the habits of the street life, in hopelessness. “I couldn’t be stuck.”

Tamara moved back in with her mom in Oak Cliff. But the problems with drugs and gangs were so bad that she knew she had to try again to get out. “A lot of kids were raising themselves there,” she said, because so many parents were in jail or on drugs.

She applied and was approved for federal housing assistance, but the only units available were in Bonton, one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the city. Bonton was built in the 1920s near the flood-prone Trinity River. Its most infamous landmark was the 1950s-era Turner Courts public housing development, so crime-ridden that buses wouldn’t stop there after dark. Not long after Robertson lived there, Turner Courts would be demolished.

“Drug selling was out in the open,” she said. Gangs were even more active than in her old neighborhood. “It was like, if I look at you wrong, you’re going to shoot me.”

Some might have backed away, but Robertson didn’t see a lot of alternatives. In Turner Courts, at least, she was in a building with mostly elderly neighbors, who looked after her and her son. “Nothing got past them,” she said. “It might not be where I wanted to be, but it was a start. I could save my money, go to school. I wanted better for my son.”

They lasted four months. Then, on an early summer day, she was outside her front door talking to a neighbor while her son, Lonzo, a preschooler, played with other children behind the building. She heard shots and kids screaming.

Terrified, Robertson ran through her apartment and found Lonzo hiding behind the back door. In the yard, lying under her clothesline, was a man she’d never seen before. Someone was still shooting, but other kids, inured to the sound of gunfire in the projects, had gone back to playing.

After making sure her son was safe, Robertson ran to where the man lay dying from multiple gunshots. She dragged him away from her building and the other kids, then ran back inside. She and Lonzo lay on the floor and waited for police to arrive, talking with their neighbor through the thin wall between their units.

When officers arrived, she told them what little she knew. “I didn’t want to know any more” about what had happened or why, she said. She just knew she wanted out. She wanted a place where her son could grow up with better choices than which gang to join, with better chances for growing up at all.

These days, Robertson, a 37-year-old self-effacing woman who radiates calm, works three jobs to support a larger family—three boys, plus a niece and her two children. They still get federal housing assistance. But they made it out.

The upscale suburb of Frisco is about 45 minutes north of Bonton, but it might as well be on the other side of the world. Robertson and her family live on a quiet street of one- and two-story brick houses with young trees in grassy front yards. The violent-crime rate in her new neighborhood, based on data compiled by NeighborhoodScout.com, is less than a quarter of what it is in Bonton; the median family income is four times as high, according to census data. At one end of the block there’s a park with playgrounds and ballfields, and at the other a hike-and-bike trail that leads to a large pond. The kids are doing well in Frisco schools, and Robertson has earned her medical assistant certificate.

This peaceful, prosperous place is a battleground, though—part of a war against racial segregation that a small Dallas nonprofit, the Inclusive Communities Project, and its lawyers have been fighting for decades. At its most basic, it’s about getting people such as Robertson and her kids the chance to live in decent housing in decent neighborhoods. In a much larger sense, it’s about reducing the kinds of economic and racial segregation that in the last year have so inflamed places such as Ferguson and Baltimore and contributed to racially motivated violence in Charleston, the burning of several black churches, even police misconduct at a teen pool party in McKinney.

During that time, Texas has been the focus of two lawsuits that housing advocates say are possibly the most important desegregation actions to come along in years, both courtesy of the Inclusive Communities Project and the small law firm that represents it. Attorney Mike Daniel and his former law partner, Betsy Julian, now president of Inclusive Communities, have been at the center of groundbreaking civil rights work in North Texas for more than 30 years.

The Treasury case in particular has the potential to change the way affordable housing is done in every state, giving poor families the chance to live in towns and neighborhoods where they’ve had little access—and little welcome—before.

The affordable housing struggle no longer centers on vouchers or big public housing projects for the poorest of the poor. Instead, it focuses on applying the anti-discrimination promises of the Fair Housing Act to low-income tax-credit housing, a major federal program in which developers receive tax breaks for building affordable residential developments. And the opponents are the most powerful that Inclusive Communities has ever faced.

On June 25, during the same two-day period when it issued momentous rulings on marriage equality and the Affordable Care Act, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Inclusive Communities in its suit against the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs (TDHCA).

That case, challenging Texas’ system for deciding where to build tax-credit projects, is already changing the landscape of affordable housing in the state. The issue that brought the case before the Supreme Court was narrow but important: the legality of a widely used standard of proof for racial discrimination. The court, in an opinion delivered by Justice Anthony Kennedy, affirmed that “disparate impact”—the idea of proving racial discrimination in housing by results, without having to prove officials’ racist intent—is constitutional. Civil rights advocates all over the country cheered the decision. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, taking the side of those who don’t want to see affordable housing in suburbs and white neighborhoods, vowed to fight on, though how that might happen isn’t clear.

Up next is a case with an even greater potential impact, but one that has drawn almost no attention. The Inclusive Communities Project is suing the IRS and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the two U. S. Treasury agencies that control the tax-credit housing program. The complaint is similar to the case against TDHCA: that the federal agencies are perpetuating racial segregation rather than trying to end it, as the Fair Housing Act requires.

The tax-credit program is the only one in the country that is adding new units of affordable housing, and it’s huge—more than 2.2 million units built in the last 30 years, at a cost of more than $6.5 billion in foregone taxes in 2012 alone. Its numerous critics charge that while it provides high-quality apartments, townhomes and houses, the program reinforces racial segregation by building most of those units in some of the worst neighborhoods in the country.

A major industry has grown up around tax-credit housing. Some of the most powerful banks in the country have billions of dollars at stake, making them committed to maintaining the status quo. The Treasury case in particular has the potential to change the way affordable housing is done in every state, giving poor families the chance to live in towns and neighborhoods where they’ve had little access—and little welcome—before. The Urban Institute reported in June that income inequality among American neighborhoods is increasing and that the Dallas area is the worst in the country. In May, Harvard economists released a study showing that growing up in neighborhoods with low-performing schools and high crime rates affects individuals’ earning abilities for their whole lives.

Daniel said that putting so much tax-credit housing into dicey neighborhoods means the program is forcing new residents into dangerous, blighted areas rather than helping them leave. Most of the people Robertson grew up with, she said, can’t even imagine getting out of their old neighborhoods to places like North Dallas or Mesquite.

Racially segregated neighborhoods are “the last line of defense in maintaining a segregated society,” said Craig Flournoy, the former Dallas Morning News reporter whose investigation, with colleague George Rodrigue, into racial segregation in public housing won a Pulitzer Prize in 1986. Flournoy now teaches journalism at the University of Cincinnati and is board president of Inclusive Communities.

“I truly believe every societal problem in this country concerning race goes back to housing patterns,” he said. “Until we address that, we will never be a post-racial society.”

In 1979, Julian and Daniel were hired by East Texas Legal Services to represent black residents of public housing in that region. The properties were segregated by race, and the units occupied by blacks were in such awful condition that in at least one building the roof had fallen in. The lawsuit the two young lawyers filed in 1980 involved the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the state of Texas and dozens of local housing authorities. It led, eventually, to the most sweeping desegregation order ever handed down, covering public housing facilities in 36 counties. Streets got paved around formerly all-black projects, sewers were fixed, air conditioning was installed, facilities were integrated. But enforcing Judge William Wayne Justice’s orders in the case took more than 20 years of continued litigation.

In the Dallas area, meanwhile, the pair was waging a long-term battle against racial segregation, from public housing placement to tactics that kept Section 8 vouchers from being used in white neighborhoods and suburbs. They went back to court when orders weren’t carried out or new rules enforced. Sometimes, all that was needed to move a recalcitrant city or agency was the threat of a lawsuit. Julian left the law firm in 1988 and when the Inclusive Communities Project grew out of a major Dallas desegregation case in 2004, she became its executive director.

As the two were getting deeper into their work on public housing, Congress was setting up a program that would radically reshape affordable housing. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 gave developers tax breaks for building housing that could be offered at below-market rental rates. A few years later, Congress let the banks in on the act, allowing the tax credits to be sold to financial institutions. Texas is one of the largest recipients of the funding.

Tax-credit housing “is a good product—good for residents, good for communities,” Julian said. The properties are usually fenced and gated and well-constructed.

But Julian, Daniel and other affordable-housing champions quickly discovered that most of the tax-credit complexes were being built in the same dead-end neighborhoods they’d been trying to get people out of, places with hazardous waste sites and low-performing schools. Developers preferred run-down areas, where land is cheap and neighbors don’t object. Plus, they could actually get extra tax credits or extra help from local banks for contributing to community revitalization efforts.

From Julian and Daniel’s point of view, the 1986 law began undoing progress they’d worked hard for.

“From 1987 to 2008, they put 17,000 [tax-credit] units into predominantly minority areas we were trying to desegregate,” Daniel said, which tripled the number of units in North Texas neighborhoods marked by slum and blight. “Most of these areas were losing population—those who could were getting out.”

Tax credits helped build places such as Eban Village, an apartment complex that was built between 1997 and 2001 near Dallas’ Fair Park. Today, the gated complex looks nice, with well-kept lawns and hedges surrounding trim brick-and-clapboard buildings that resemble the bungalow-style homes wealthy Jewish citizens built along nearby Park Row in the early 20th century. A community center, retail stores, small restaurants and public transportation are nearby.

Just outside the gates, however, it becomes clear why the neighborhood is rated as deeply distressed. Run-down houses are common, and day drinkers hunker on a nearby corner.

A large and lucrative industry has grown up around building and operating tax-credit housing. Myron Orfield, an influential demographer and law professor from Minnesota who has studied and written extensively on the subject, calls it the “poverty housing industry.” Nonprofit organizations are often involved, but Orfield said they are usually just the “friendly face” for the community, with the same for-profit builders, banks and investors ultimately benefitting.

Banks are frequently willing to participate because it’s easier to fulfill their community investment responsibilities than to make their loan programs more equitable, he said. “If you’re a businessman and you don’t care about ghetto-building in the inner cities, it makes a lot more sense,” he said.

Some of the biggest banks in the country are major players. Wells Fargo, Bank of America, J.P. Morgan and Citibank each invested about $300 million in tax-credit housing over a two-year period.

John Henneberger, co-director of the nonprofit Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, said the same problem exists in many states. A 2013 study by the Fair Housing Justice Center found that almost three-fourths of tax-credit housing units for families in the New York City area were concentrated in high-poverty neighborhoods, while similar housing for the elderly—occupied mostly by whites—had been built mostly in higher-income suburbs.

“There is overwhelming evidence in the social science community about the harm that comes to children who grow up in neighborhoods that have these extreme rates of poverty and violent crime,” Henneberger said.

Niketa Ramsey has seen the effect firsthand. A year ago, she and two of her children moved from Sunnyside to Sunnyvale—that is, from Houston’s high-crime (though gentrifying) Third Ward to a little upscale town east of Dallas and into a tax-credit-financed townhome built as a result of Inclusive Communities’ relentless hammering on getting such housing into the suburbs.

The change “did wonders for me and my kids,” who are both teenagers, she said. The schools are much better than in their old neighborhood, and her son’s reading skills improved by two grade levels. There’s more for them to do in the community, and they can play outside “without me having to watch every minute.” Ramsey is planning to apply to nursing school.

“It’s peace,” she said.

“I truly believe every societal problem in this country concerning race goes back to housing patterns,” he said. “Until we address that, we will never be a post-racial society.”

Ramsey, like Robertson, is an Inclusive Communities client. Besides its groundbreaking legal work, the nonprofit has a mobility program to help low-income families find housing outside of their old neighborhoods and assist with moving costs such as security deposits and fees.

In the Harvard study released in May, economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren wrote that the effects on children of living in poor neighborhoods intensify over time, and are a major factor in long-term poverty. In their much-heralded work, the researchers concluded that getting out of such neighborhoods early on significantly improves children’s chances of going to college and, for young women, reduces their chances of becoming single parents.

“The evidence is mounting: It can be lifesaving for kids [to get out of bad neighborhoods]. You just can’t keep holding people hostage to the idea of making it into a garden spot,” Julian said. “You shouldn’t use hostages to fight wars.”

“We know you’re going to screw it up for the rest of us.”

That’s how Mike Daniel describes the view of his civil rights colleagues as he prepared to present the TDHCA case to the U.S. Supreme Court on Jan. 21. The civil rights community was terrified that Inclusive Communities was about to kill off something valuable to all of them, he said.

In a long career of fair housing and other civil rights cases, it was Daniel’s first time to argue a case before the Supreme Court. At issue was the fate of disparate impact as a way to attack racial discrimination under the Fair Housing Act.

The court had agreed twice before to hear the issue, only to have the cases settled out of court—civil rights advocates had been trying to keep the question out of the Supreme Court’s purview for several years, fearing that the conservative lean of the court would mean a disastrous ruling. And now the Inclusive Communities case had thumped the theory down in front of the justices in a very public way.

“The tension it caused everybody was horrible to watch,” Daniel said. But even if he and Inclusive Communities had wanted to, there was no way they could have kept the Texas housing case from reaching the Supreme Court, not with Greg Abbott running for governor last year and boasting that suing the Obama administration was practically Job One for him.

The odd thing was that, well before Abbott’s decision to appeal the 5th U.S. Circuit’s ruling in the case, the Texas housing agency had already put into place the reforms that Inclusive Communities had sought.

That happened in 2012, after U.S. District Judge Sidney Fitzwater ruled that the agency had racially discriminated in choosing which tax-credit projects to fund. He required officials to file a plan to remedy the problem. The agency did so, revising its criteria on how to rate developments seeking federal tax-credit support. But instead of applying them only in the area covered by the Inclusive Communities suit, the agency voluntarily put the changes into effect statewide.

By the time of the January arguments, tax-credit housing had already begun to be built in places that had never welcomed affordable housing, including Sunnyvale (where Niketa Ramsey and her family live), Frisco and McKinney. True, in many cases the tax-credit housing was approved only with the help of an additional kick in the municipal pants from Inclusive Communities, via lawsuits or threats of same.

“TDHCA faced up to and solved the problem,” Henneberger wrote recently. And yet Greg Abbott, as attorney general, “mounted a misguided appeal to undo a half century of civil rights progress in fair housing.”

Abbott found plenty of allies, including the American Bankers Association and a long list of mortgage industry groups, all of which filed amicus briefs in the case, as did the Texas Apartment Association.

On the other side, once it was clear the TDHCA case wasn’t going away, the civil rights community eventually closed ranks to support Inclusive Communities and disparate impact. In addition to major civil rights groups, 17 states, a prestigious group of more than 60 housing scholars, and a long list of cities filed briefs on behalf of Inclusive Communities—a fact Kennedy noted in his majority opinion.

Daniel, his current law partner Laura Beshara, and the Inclusive Communities leaders had decided that they would put the heart of the Fair Housing Act—its goal of eliminating racial discrimination in housing—at the center of their brief.

“If we were going to go down, we were going down on our own terms,” Julian said. During arguments, civil rights advocates saw some reason for hope in the justices’ questions. But Daniel and Julian were pessimistic all spring, waiting for the court’s decision and working on the Treasury case.

If the federal government isn’t going to aggressively enforce the requirements of the Fair Housing Act on others, shouldn’t it at least stop segregation in its own programs?That’s the question Julian has been asking for decades, and it’s one that inevitably led Inclusive Communities to sue the IRS and OCC. While many housing desegregation lawsuits have taken on states and cities and HUD, nobody until now has gone after the Treasury agencies. As in the TDHCA case, Inclusive Communities alleges that the Treasury agencies have allowed the tax-credit housing program to aggravate racial segregation in the Dallas area rather than alleviate it.

The IRS administers the tax-credit housing program while OCC oversees the banks. National banks are allowed to invest in real estate only if the project is deemed to be promoting the public welfare. OCC has to sign off on that in order for banks to be able to take part in the lucrative business of trading tax credits and otherwise making money off of the housing properties.

“They like to say it’s a tax program,” Julian said. “Well, it’s a housing program.” In fact, it’s the largest affordable-housing program in the country. Nonetheless, neither Treasury agency has ever written any regulations to prevent or deal with racial segregation in the program. When groups such as Inclusive Communities sue states and local governments for using the tax-credit money in a way that promotes segregation, they can’t point to any federal regulation that’s not being followed.

What they can use is the Fair Housing Act, which requires that agencies “affirmatively further” fair housing by eliminating racial segregation in housing programs.

The tax-credit housing program, Daniel said, was created “with a lot of high ideals” about promoting public welfare by making affordable housing also profitable for builders. Now, rather than any detailed showing of how a proposed project will benefit the public welfare, he said, there’s just a one-page form to submit.

When Barack Obama was elected president, Inclusive Communities started nudging the Treasury to develop regulations to enforce Fair Housing Act standards in the tax-credit program. But it hasn’t happened.

“They talked and talked and talked,” Julian said. “I believe Treasury has no intention of doing anything until they are forced to. They are incredibly arrogant … [and] certainly heavily influenced by the industries they regulate.”

Lately, Obama seems to have moved closer to Inclusive Communities’ position, devoting one of his weekly radio addresses to the topic of fair housing. “The work of the Fair Housing Act remains unfinished,” he said. Referring to the disparate impact ruling, the president said the Supreme Court had acknowledged that “too often, where people live determines what opportunities they have in life.” In June, his administration released new rules aimed at reducing segregation in federally supported housing. However, the rules focus on improving local accountability rather than addressing Treasury’s actions.

Inclusive Communities’ case against the Treasury agencies is Dallas-based, and the nonprofit is asking for Dallas remedies. But if the courts rule that the IRS and OCC “have to stop allocating housing in areas of slum and blight, then it will have an impact nationally,” Julian said. “That is why everyone is hysterical.

“I don’t begrudge people making money,” she said. But tax-credit housing “is a very rich program. And it is serving a lot of people before it serves poor people.”

Jill Khadduri of Abt Associates, a former HUD executive, has argued that there needs to be a better balance of tax-credit units in poor neighborhoods and in so-called high opportunity areas—that is, middle-class neighborhoods. “It hasn’t been so much a question of deliberate segregation as missed opportunity,” she said.

Mark Shelburne, a senior manager at Novogradac & Company, is a consultant to government agencies, builders and others on tax-credit housing. He is skeptical of claims that the program has added to urban blight and racial segregation. But he does agree that the Inclusive Communities suit could have “huge consequences for the tax-credit industry.”

Despite that, he said, “bankers mostly don’t know about the [Treasury] suit. The fact is, it’s the same plaintiffs, the same judge, a lot of the same facts [as in the TDHCA suit]. And who’s to say there will be a different outcome? So far, Inclusive Communities is winning.”

Kennedy, in the majority opinion in the TDHCA case, wrote that government-backed segregation by race “was declared unconstitutional almost a century ago, but its vestiges remain today, intertwined with the country’s economic and social life.”

Richard Rothstein, a researcher with the Berkeley law school and the Economic Policy Institute, takes a much more cynical view. In an article in the American Bar Association’s Human Rights Magazine, he argued that racial segregation in urban America, at least since the 1930s, has been strengthened, if not created outright, by the federal government, through mortgage discrimination, rules barring blacks from many developments, and programs aimed at moving white families to the suburbs. But at least as late as 2007, he wrote, the Supreme Court was acting as though racial segregation was, in effect, just something that happened.

“There is overwhelming evidence in the social science community about the harm that comes to children who grow up in neighborhoods that have these extreme rates of poverty and violent crime.”

It’s not surprising that the justices were ill informed, he stated. “We suffer from collective amnesia about racial history, comforting ourselves that Jim Crow was restricted to Southern states with blunt racial legislation,” he wrote.

Texas officials didn’t exhibit the visceral reaction to the decision on housing equality that they showed with the court ruling on marriage equality. The case is “far from over,” Paxton stated in a release. He also wrote that the housing agency’s decisions on doling out tax-credit housing money were made with the “legitimate objective of revitalizing neighborhoods.” Julian and Inclusive Communities aren’t trying to prevent all units from being placed as part of a redevelopment of bad neighborhoods; they’re just trying to get some of them into the suburbs and good neighborhoods as well.

Tim Irvine, executive director of the TDHCA, did not agree to an interview, but in a statement provided to the media after the decision, he said his agency “remains committed to its mission of providing affordable housing options to low-income Texans.”

Whether the TDHCA case is over seems to be up to Fitzwater, the district court judge. The Supreme Court let stand the 5th Circuit’s decision to send the case back to the trial court judge to reconsider some points. But the justices didn’t order up a retrial or any particular action at all—they left that to Fitzwater.

At this point, Daniel said, Texas is now in the forefront of states trying to spread the wealth of low-income housing opportunities to better neighborhoods. “Sad to say, it doesn’t take much” to lead that pack, he said.

Because of Inclusive Communities’ fight, Henneberger said, “properties actually being funded today are largely in neighborhoods where a reasonable person might want to live.”

Tamara Robertson is trying to make sure her kids get the full story. She takes them to visit her mom, back in a rough part of Dallas, so they can see what it’s like. “I get so excited. I feel like I’ve been coming such a long way,” she said. When Lonzo graduates from high school in two years, she said, she’s going to get off housing assistance and go back to college, even if she has to take a fourth job to make it happen.

Orfield, the Minnesota housing scholar, said that if Inclusive Communities wins the Treasury case, “we will see more affordable housing throughout the country in whiter areas.”

The connection between desegregating American communities and tragedies such as the police shootings in Ferguson and Baltimore is an important one, Orfield said. “Places that have really integrated schools and affordable housing in the ’burbs don’t have these problems.

“If you create big ghettos, you are going to have Fergusons—farther from employment and closer to prison,” he said. What Inclusive Communities is doing “is at the very center of what the solution is going to be if we ever want to deal with the problem.”