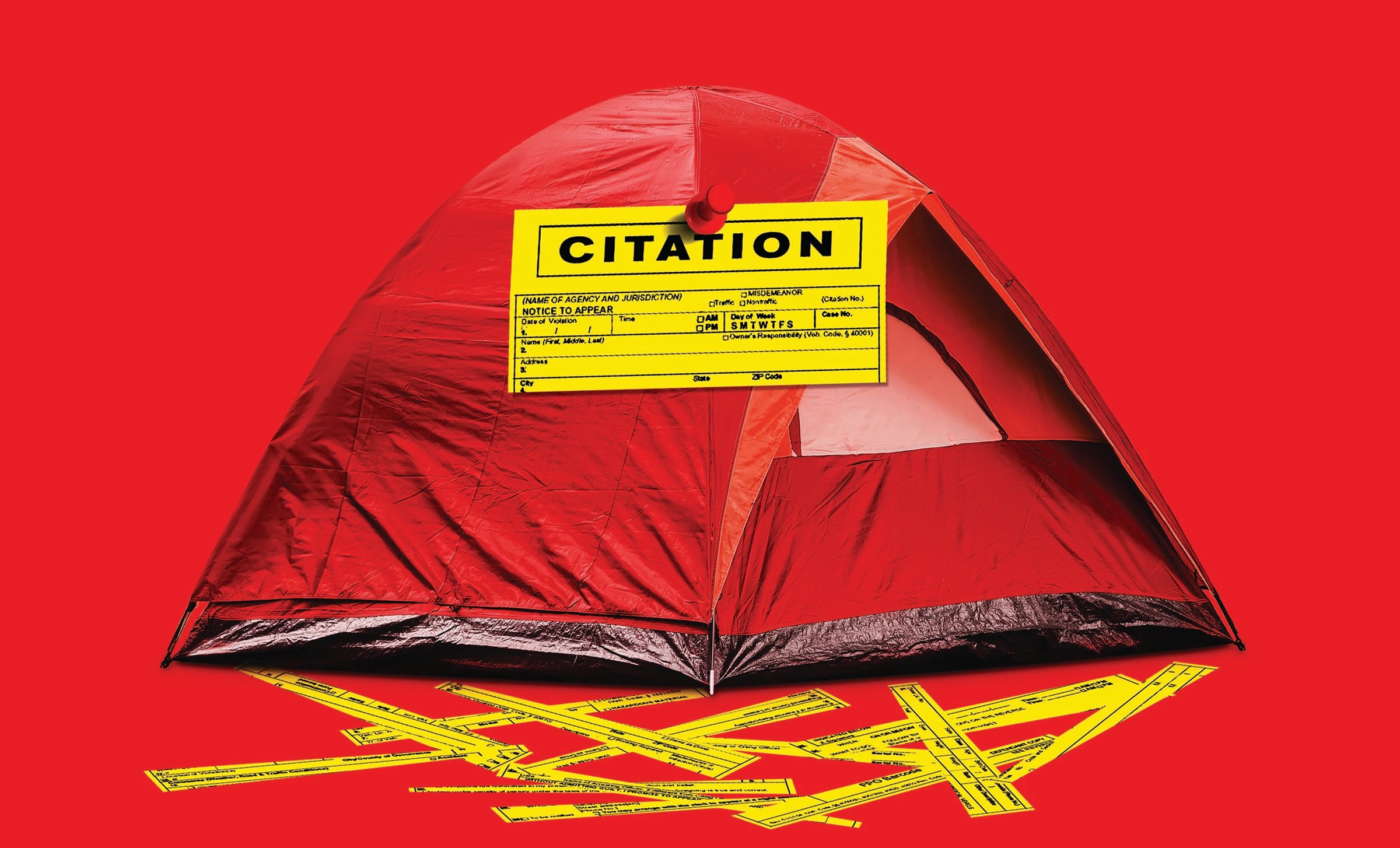

The Waiting Game

With no place to go, many Texans with intellectual disabilities end up on the streets.

A version of this story ran in the November 2015 issue.

It’s 9 a.m. on one of the coldest days of the year, and 33-year-old Betty Calderon is brushing her long black hair in anticipation of seeing her fiancé. For the last two weeks, Ernest Rodriguez has been locked up at the Travis County jail for aggravated assault by strangulation. He is accused of choking Calderon until she almost blacked out.

That night in November 2014, the couple was getting ready to bed down in a parking lot in one of the few pockets of East Austin that hasn’t been gentrified. Calderon was scrolling through the prepaid cell phone she’d purchased for Rodriguez with her disability income when she discovered intimate messages he’d exchanged with another woman. She confronted him. Tempers flared. It wasn’t the first time Rodriguez had choked her. This time, though, the cops showed up before she passed out.

“He was pushing my wind really hard, and I had weak breathness,” Calderon says a few weeks after the incident, the bruises on her neck finally fading. “But I still have feelings for him. I pray for him every day and tell him goodnight every time I go to sleep.”

Calderon has been homeless for more than two years. She receives Social Security disability income, but because of an intellectual disability, she has trouble managing money. People steal from her and sometimes she splurges on things like Air Jordans and can’t afford to buy food at the end of the month. Calderon has Type 2 diabetes, which is tough to manage when food is something you find rather than buy. Her dental hygiene has deteriorated to the point that decay has eaten a hole in her front two teeth.

With Rodriguez in jail, Calderon says she struggles. He protected her — when he wasn’t hurting her — and helped her find food and places to camp. They would take turns at night guarding their spot while the other slept.

Calderon’s situation highlights an overlooked demographic: those who are homeless and have intellectual disabilities, generally defined as having an IQ below 70 and lacking the social, conceptual and practical skills needed to manage everyday life. With regard to the well-being of citizens with intellectual disabilities, Texas ranks 50th among the states and the District of Columbia, according to the nonprofit United Cerebral Palsy. Only Mississippi is worse.

Research on the intersection of homelessness and limited cognition is sparse but the best estimate is that about 9 percent of homeless adults have an intellectual disability, compared to 1 to 3 percent in the general population.

As many as 73,000 Texans with intellectual disabilities are on a waiting list to receive home- and community-based services, such as employment assistance, behavioral counseling, dental care and placement in small group homes with around-the-clock caregivers. (In contrast, at least 17 other states have waitlists with fewer than 1,000 people.) For someone signing up today, the wait to receive services could be as long as 14 years. Some people caught in limbo have families who can house and support them in the interim. Others, including Betty Calderon, make do the best they can.

There is no official estimate of how many people on the list are homeless. But experts say that Texas’ failure to fully fund services forces some people with cognitive impairments onto the streets, where survival requires quick wits.

Dennis Borel, executive director of the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, says that underfunding social services and housing support means that taxpayers spend more when people end up in jails and hospitals. “This is a huge problem for the state of Texas,” Borel says.

Meanwhile, Betty Calderon is used to waiting. She’s been waiting her whole life, it sometimes seems, for someone to help her.

More than anything, Calderon wants to find permanent housing where she can live with her children. “I miss them,” she says. “They’re my babies.”

After graduation, she met Chris Foley, a man almost 20 years her senior. He proposed to her at the Highland Mall food court, though they never married. The couple had two children and lived in a public housing development. In 2011, Foley died of cancer, according to Calderon’s parents, but she says he succumbed to AIDS.

“When she was with Chris she had no problem,” says Calderon’s father, Ralph. “When Chris died she couldn’t take it.”

Without a partner, Calderon was adrift.

“He was my everything,” she says. “He gave me a place to stay, he gave me kids and he always went to work.”

After Foley died, Calderon had a child with a boyfriend. Her mother says Calderon had a hard time keeping her three children clean and fed. Not long after her youngest was born, Texas Child Protective Services removed the children from the home. “CPS said I wasn’t taking care of them,” Calderon says.

In July 2012, a court granted custody of the children to Calderon’s aunt. Calderon has the right to visit them with supervision. She rarely sees them, though, because her aunt doesn’t like it when she visits, Calderon says.

More than anything, Calderon wants to find permanent housing where she can live with her children. “I miss them,” she says. “They’re my babies.”

After losing custody, Calderon moved into a trailer owned by her father on the eastern edge of Austin. Six months later, he could no longer afford the mortgage, and at the start of 2013, Calderon was suddenly homeless. She spent her first night on the streets behind a Jack in the Box.

In the beginning, she was lost. It took her months to figure out the best places to get a meal, the safest places to camp. Afraid of being attacked, she was restless at night. When Rodriguez entered the picture, she finally settled into a routine. For fun, they would watch her favorite movie, Blood In Blood Out, on a portable DVD player. They would visit a storage unit she rents in South Austin. It’s piled high with the stuff that to her means home— a BMX bike, a TV that doesn’t work, old luggage.

When I met Calderon in May 2014, she had recently found her way to Parker Lane United Methodist. She and Rodriguez had been camping near a creek in a leafy park until a police officer ordered them to leave. At Parker Lane, they built a makeshift structure out of scavenged cardboard and a blue plastic tarp strung between the church and a retaining wall.

The church’s groundskeeper alerted Pastor Tina Carter. The next morning, Carter poured a cup of coffee and walked the 200 feet from the parsonage to the temporary shelter.

“Hello,” Carter said as she approached the couple. “I’m Tina, what are your names?”

She told Rodriguez and Calderon that although they couldn’t camp on the church property, she would help them find housing.

Carter has a stepson with autism and knows more than most about people with cognitive disabilities and the obstacles they encounter when trying to get services. Many people with mild intellectual disabilities, including Calderon, read at a grade-school level at best, and applying for services is often an exercise in gathering and filling out paperwork. An advocate, a friend or family member, is almost essential to navigate the process.

Carter thought a well-run group home in a residential neighborhood with around-the-clock access to a professional caregiver might be ideal for Calderon. It would get her off the street and potentially save her life.

Texas relies largely on 13 campus-like facilities — once called state schools and recently renamed State Supported Living Centers — to care for the intellectually and developmentally disabled. These institutions have been the sites of horrific abuse, with hundreds of documented cases in which staff neglected, beat and even killed residents. In the most notorious example, staff at a Corpus Christi state facility organized a late night “fight club”; residents were encouraged to violently attack each other. Things were so bad that in 2009 the U.S. Department of Justice sued the state for civil rights violations and, as part of a settlement, now requires close monitoring and inspection of the state schools.

In the last few years, Texas has worked to move people with intellectual disabilities from the state schools to residential settings, including small group homes with caregivers who provide supervision, support and the encouragement to perform daily tasks such as preparing meals, practicing personal hygiene and managing money. Advocates say such an approach fosters independence, social inclusion and self-esteem.

While most advocates welcome the shift, a fundamental problem remains: chronic underfunding. Texas ranks 49th in the country for spending on community-based services for people with intellectual disabilities, according to a 2013 report from the University of Colorado.

In July 2014, two months after meeting, Carter and Calderon went to an appointment with a social worker at Austin Travis County Integral Care, the local authority that coordinates state services for the intellectually disabled. The explanation of the group home placement process — full of acronyms and contingencies — was mystifying, even to Carter.

“I’ve got a Ph.D. in applied chemistry and a master’s degree in divinity,” Carter says. “If I couldn’t understand it, the chances that Betty had were pretty much zero.”

Still, Carter helped Calderon track down the identification she needed — a Social Security card and a photo ID — and fill out the paperwork to get on the waitlist. Even if she qualified, she could wait up to 14 years to get placed in a group home.

Several weeks later, I ask Calderon about the paperwork.

“I don’t know where it is,” she says.

She never did find it. And Carter got busy with her church duties, a sick daughter and her own health issues. Without an advocate, Calderon had no idea how to pick up where she left off.

For two months, she found safe harbor in a small room next to the church gymnasium. Carter laid out simple rules for the couple, who were still together then. There was to be no alcohol and no violence. They were happy, until Rodriguez lost his temper. “I just got angry and I choked her,” Rodriguez told me.

By October they were back on the street again. The next time Rodriguez hurt Calderon, he would end up in jail.

Crashing on the floor of her parents’ apartment isn’t pleasant, but it’s safer than the street, where she’s been robbed and violently harassed. She once landed in the emergency room after not having anything to eat for three days.

Calderon sleeps on an inflatable mattress in the living room. She leaves a light on at night to keep the roaches away.

Crashing on the floor of her parents’ apartment isn’t pleasant, but it’s safer than the street, where she’s been robbed and violently harassed. She once landed in the emergency room after not having anything to eat for three days.

Still, Calderon prefers the uncertainties of life on the street with a man who chokes her to the suffocating atmosphere of her parents’ place.

“I like to be close to someone,” she says.

On the day Calderon goes to visit Rodriguez in jail, she’s smiling. She hasn’t stopped smiling all day.

She stands in line for 20 minutes, expecting to get a visitation number and wait a few hours. She hadn’t made an appointment. She didn’t know she could. She finally gets to the receptionist, who sits behind a bulletproof glass wall and passes her ID through a slot. Without making eye contact, the woman feverishly types on a keyboard. After several minutes, she looks up at Calderon.

“You can’t see him,” she says, “You have an E.P.O.”

Calderon didn’t apply for an emergency protective order. (It’s standard procedure for police handling domestic abuse to file protective orders.)

There’s nothing the receptionist can do. The smile disappears from Calderon’s face.

“I didn’t want for him to get locked up. I still want to be with him,” she says.

As she leaves the jail, she pushes open the heavy glass doors and a burst of cold air hits her in the face.

“I’m trying to get a social worker that can help me get my kids back,” she says, “and maybe we can all even get a place together.”

[Featured image credit: Matthew Mahon]

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.