Rick Perry’s Refusal to Expand Texas’ Medicaid Program Could Result In Thousands of Deaths

A version of this story ran in the January 2013 issue.

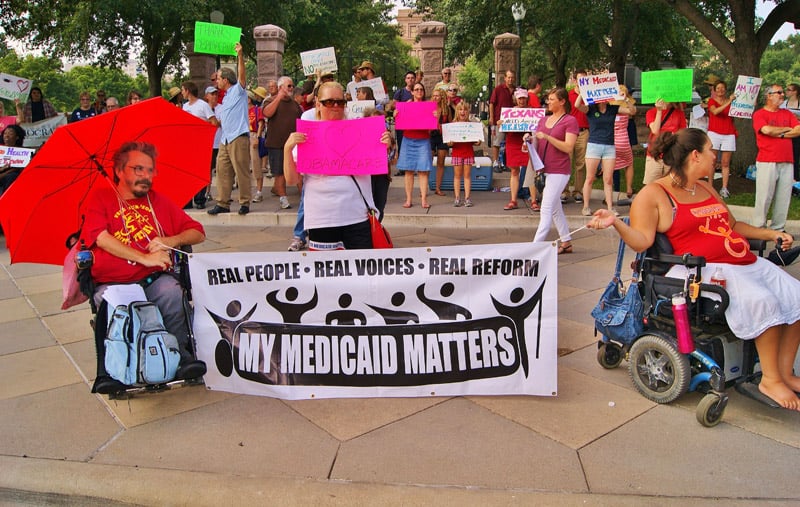

Above: Members of the Texas Chapter of ADAPT celebrate the United States Supreme Court’s upholding of the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, in front of the Texas Capitol.

You could say that the idea for Medicaid began in Texas. In the late 1920s, a middle-school teacher named Lyndon B. Johnson saw the crushing poverty and inequality his Mexican-American students faced in the small South Texas town of Cotulla. Nearly 40 years later, then-President Johnson declared a War on Poverty and, in 1965, signed the bill that created Medicaid—a program funded jointly by the states and the federal government to provide health insurance to low-income Americans. It was part of his vision for a “Great Society,” which he boldly defined as “a society where no child will go unfed, and no youngster will go unschooled.”

Johnson probably couldn’t have imagined the program’s impact. In the past 47 years, Medicaid has provided medical care to hundreds of millions of Americans—including low-income children, the elderly, disabled, and pregnant women—and has saved millions of lives. More than 50 million are currently enrolled.

In Johnson’s home state, however, the commitment to Medicaid has always been lackluster at best. Texas’ Medicaid program spends less than the national average per enrollee, and reimburses doctors, hospitals and other providers less than the national average. In many areas, the Texas program pays for only the minimum standards required by the federal government. One in four Texans—6.1 million people—lack health insurance, the highest percentage in the country.

Now another Democratic president wants to expand Medicaid, under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or “Obamacare.” Even a modest expansion would mean that an estimated 1.5 million working adults who earn 133 percent of the federal poverty level or less (about $14,856 a year for an individual) could have health insurance starting in 2014.

But there’s one big snag. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in June that states have the right to refuse to expand Medicaid. Texas Gov. Rick Perry is among several governors, mostly southern and Republican, who are resisting. To make the expansion more palatable, the federal government will pay for all the people added to Medicaid rolls until 2017; after that, it will reimburse 90 percent of the costs. In effect, Americans around the country would help pay for the health insurance of more than a million Texans.

If Texas doesn’t expand Medicaid, it will reject more than $100 billion in federal money the first decade, according to the state’s own figures. To get that sizeable federal reimbursement, the state would have to spend about $16 billion over 10 years. The governor’s refusal to take the federal government’s billions puts him in an awkward position opposite some of the state’s most powerful economic players: hospital chains, local governments and chambers of commerce. Given that political pressure, Perry might strike a deal with the Obama administration, or the Texas Legislature could push for a Medicaid expansion.

Beyond the economics and politics, lives are at stake. Lack of insurance will certainly mean more deaths. How many more? Approximately 9,000 a year, according to Dr. Howard Brody, director of the Institute for Medical Humanities at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. Brody calculated that figure by extrapolating from a recent Harvard University study published in The New England Journal of Medicine that found that states that expanded Medicaid saw a 6.1 percent reduction in the death rate among adults below 65 who qualified for the program. In a recent op-ed in the Galveston Daily News Brody wrote, “This means that we can predict, with reasonable confidence, if we fail to expand Medicaid . . . 9,000 Texans will die each year for the next several years as a result.”

Too often the political debate around Medicaid expansion is about dollars and cents, Brody told me recently. “It’s presented as if it weren’t about life and death,” he said. Brody teaches ethics to medical students at UTMB, so for him, the issue of Medicaid expansion, when you cut through the rhetoric and endless policy discussions, is a deeply moral question: Should Texas allow people to die simply because they can’t afford health insurance? “Whose life and death are we talking about?” said Brody, who treated Medicaid patients for decades before becoming a professor at UTMB. “Politically, the Medicaid population are simply invisible folks. Most Americans may not care very much, because they think, ‘I’m not in that group of people and that’s somebody else and so it’s somebody else’s problem.’”

Perry has contributed to this attitude by arguing that uninsured Texans can receive health care in emergency rooms. “Everyone in the state of Texas has access to health care, everyone in America has access to health care,” Perry said at a New Hampshire campaign event in November 2011, according to the liberal website ThinkProgress. “From the standpoint of all people in this country, our government requires that everyone is covered.” Perry is correct that anyone can get treated in an emergency room—but it’s expensive. And not everyone in Texas has access to health care. People with chronic conditions—especially those with cancer—face a bleak future without health insurance. They are among the thousands of Texans whose lives could be saved by Medicaid expansion.

For 15 years, Mario Reyes, a diabetic, bounced from one emergency room in San Antonio to the next. On some days his blood sugar was so high he feared he might black out while driving to the hospital.

A commercial painter by trade, he’d worked his entire life, but had never been able to afford health insurance. For years, like nearly 400,000 other uninsured residents in Bexar County, he’d relied on the local emergency room for treatment. Most months he would visit the ER at least twice for his diabetes. Then, two years ago, at the age of 52, he developed a constant, debilitating pain in his lower back. After a few excruciating weeks, Reyes finally went to the hospital. He felt numb when the doctor gave him his diagnosis. Reyes had kidney cancer.

For Reyes, the diagnosis felt like a death sentence. “I couldn’t work and I had no money and no health insurance,” he says. For Reyes, uninsured and living in Texas, a diagnosis like cancer meant he was at the mercy of a charity organization, or possibly a county indigent program. Reyes was more fortunate than most. He found Methodist Healthcare Ministries, a church-based charity health-care system, which referred him to a specialist who removed his cancerous kidney. Methodist Healthcare Ministries underwrote almost all of the costs of Reyes’ surgery and care.

“My husband wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for them,” his wife Mary said. But Reyes and his wife believe that he wouldn’t have gotten so sick to begin with if he’d had health insurance all those years. “I’m surprised he’s still here, because his sugars were always so high,” Mary says. “I feel blessed he’s here next to me.”

Reyes received life-saving treatment because he happened to live in a large metropolitan city with significant charity care for those without insurance. If he had lived in a rural county, we probably wouldn’t have had our recent conversation on a warm, sunny morning in San Antonio. The outcome had been very different for a 27-year-old East Texas man with the same diagnosis that I wrote about in a 2009 Texas Observer story (see “Sick + Tired,” Sept. 3, 2009). Sam, who was also uninsured, died because he couldn’t find anyone who would treat his cancer.

Reyes was lucky enough to find a charity program in his hometown. But even with the charity and indigent health-care programs that San Antonio offers, only a fraction of the county’s uninsured residents will get help, said Kevin Moriarty, CEO and president of Methodist Healthcare Ministries. “For every 2,000 or 3,000 that we cover, there are probably 20,000 or 30,000 that are not covered,” he said. “And they don’t get to us. And how unfair is that, that somebody’s tumor that could be removed, that someone’s life that could be extended, ends because we don’t have access to the resources to make that happen?”

Medicaid expansion would help people like Mario Reyes, said Moriarty, who is frustrated by Perry’s rejection of the program in Texas. “We’re talking 1.5 to 3 million people around the state who are going to get late care or no care,” he said. “They’re going to suffer, they’re going to be in pain because we can’t make a better policy decision.”

Perry has been a fierce opponent of the federal health-care reform bill since it passed. “Freedom was frontally attacked by passage of this monstrosity,” he told the media after the Affordable Care Act passed Congress in 2010. “Obamacare is bad for the economy, bad for health care, bad for freedom.” After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June upheld Obamacare but allowed states to opt out of the Medicaid expansion, Perry fired off a letter to Kathleen Sebelius, secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, calling the notion of Medicaid expansion and the creation of a state-level insurance exchange—another element of Obamacare—a “brazen intrusion into the sovereignty of our state.”

“What they would do is make Texas a mere appendage of the federal government when it comes to healthcare,” he wrote Sebelius. “Neither a ‘state’ exchange nor the expansion of Medicaid under the Orwellian-named PPACA would result in better ‘patient protection’ or in more ‘affordable care.’”

Two hours after sending his letter, Perry was on Fox News comparing the Medicaid expansion to “adding 1,000 people to the Titanic.” Instead, Perry said, states like Texas should be given Medicaid block grants to create their own system for health-care coverage, without elaborating further on what that system might entail. Fox News correspondent Jenna Lee, much to Perry’s visible annoyance, began to press him for specifics. “According to a new federal government report—I know you’ve seen this—Texas has ranked last when it comes to health services provided by the state,” Lee pointed out. “The facts are one out of four Texans is without health insurance. One out of four Texans is on Medicare or Medicaid. The health crisis, the big crisis for the country and for your state, what is one solution you are offering to the citizens of Texas?”

Perry blinked for a moment. “The idea that this federal government, which doesn’t like Texas to begin with, to pick and choose and come up with some data and say somehow, Texas has, you know, the worst health-care system in the world is just fake and false on its face.

“The real issue here is about freedom,” Perry insisted. “Every Texan has health care in this state. From the standpoint of having access to health care, every Texan has that. How we pay for it and how we deliver it should be our decision.”

Health-care advocates could only shake their heads in dismay after Perry’s Fox News performance. The job of providing a health-care safety net has increasingly fallen on hospitals, counties and local taxpayers. To patch together a system of care, large metropolitan counties like Bexar have taxed themselves to create health districts and to fund public hospitals. Rural counties, with their limited pools of property taxpayers, don’t have that option, and provide fewer services to residents.

For at least 37 years, Kevin Moriarty has been involved in the debate over how to treat Texas’ uninsured. For decades he worked in San Antonio’s Department of Human Services. Then, in 1995, he became president and CEO of the nonprofit Methodist Healthcare Ministries, which funds its charity care from profits generated by hospitals it co-owns with HCA, a for-profit hospital chain.

In the past two decades, Methodist Healthcare Ministries’ charity care costs have grown from $200,000 to $72 million. Each year, Methodist Hospital and other Bexar County hospitals write off millions in unpaid emergency room charges. In 2010 alone, Methodist racked up $221 million in unpaid emergency room bills, according to a July 2012 report by the Kronkosky Charitable Foundation. Increasingly, the burden of underwriting charity care falls to the insured, who pay an average of $1,500 to $1,800 per year per family in extra costs, according to Anne Dunkelberg, associate director of the progressive Center for Public Policy Priorities.

Hospitals and physicians see the Medicaid expansion as a smart business decision, Moriarty said. “Every hospital system, every health-care provider, every physician in the state is suffering from a lack of revenue from health care,” he said. “Now, Medicaid is not their solution. However, it will take away what might be 10 to 20 percent of their charity care expenses. Every physician’s office, every dentist’s office that takes Medicaid, will see improvements to their bottom lines.”

Perry and other opponents of the expansion, such as the conservative think-tank Texas Public Policy Foundation, argue, however, that the expansion will cost the state too much. They contend that Texas will be on the hook if the federal government becomes less generous with reimbursements in the future. Or as Perry put it in a 2010 op-ed after the Affordable Care Act passed, “Staggering costs handed down to generations yet unborn.”

But the costs don’t seem so staggering when you look at a recent report by economist Ray Perryman, who estimated that Medicaid expansion would result in total cumulative gross benefits to the state economy of $270 billion in the first decade and a boost in employment. This, Perryman wrote, would come from health-care spending provided through expansion, reduction of uncompensated care (and thus the local government and private funds needed to pay for it), and reduction of chronic illness and death through better health care, and thus more productivity.

Whether Texas expands Medicaid or not, Perryman emphasized, taxpayers will still be paying for it. If Texas passes up the Medicaid expansion, it will forfeit an estimated $100 billion in federal reimbursements in the first decade. Some of this money will come from Texas taxpayers and be redistributed to other states for their own Medicaid expansion programs. “The relevant question at present is not philosophical, but practical,” Perryman said. The expansion “represents one of those rare occasions where Texas can both provide significant services for many of its least-advantaged citizens while simultaneously stimulating the economy and taking the most fiscally responsible course. Whether Texas opts in to this program or not, our citizens and businesses will pay the federal taxes that support it.”

It would be foolish to reject billions, especially if we’re paying for it anyway, Moriarty said. “Here you’ve got these very conservative individuals arguing that we shouldn’t accept this money because of the burden to the Texas taxpayer. But an important fact about what’s being proposed is, by not accepting these funds, we’d be taxed twice. First of all, we won’t get our state monies back from the federal government. And secondarily, as a property owner, I pay hospital district taxes, and so I’m paying and subsidizing these costs at a local level.”

The prospect of rejecting so many billions is giving county officials heartburn. Some of the state’s biggest metropolitan counties are looking for a way around Perry and other state leaders if they continue to block Medicaid expansion. In August, George Hernandez, president and CEO of University Health System in San Antonio, which runs the indigent program in Bexar County, made national headlines after he proposed that Texas’ six most populous counties band together to circumvent the state and apply for the federal Medicaid expansion money on their own.

Most counties are already tapped out, having formed local taxing districts to fund public hospitals and indigent programs. Hernandez’s University Health System has 55,000 uninsured county residents enrolled in its indigent program. Each person in the program costs county taxpayers $2,000 a year, he said.

At least 26,000 of those patients could be covered under the Medicaid expansion. “That’s a $53 million savings every year to Bexar County taxpayers.”

When I spoke to Hernandez recently, he wanted to de-emphasize the county-led effort and focus instead on a statewide solution. “It could reform the inequities in the existing system,” he said. “Right now we have a county-based approach under the Texas Constitution—254 counties provide health care in 254 different ways. Rural counties are only putting 8 percent into their indigent health-care programs because that’s all they’re required to do under state law. While the urban counties, including Bexar, Tarrant and Harris, are putting 40 to 50 percent of their budgets into health care.”

Urban counties are disproportionately carrying the load for the whole state. “When you have a health crisis and you’re in a rural county, what do you do?” Hernandez said. “You move into an urban county to get health care much the same way families move school districts to get into the right school.”

In his mind, one of the most powerful arguments for Medicaid expansion is to equalize that expense and lift some of the burden from urban areas and urban taxpayers. “This is what moved our chamber of commerce to support the Medicaid expansion,” he said. “The business community knows that there is an unequal burden that our taxpayers are paying.”

In politics as in health care, nothing is as easy as it should be. Despite the compelling economic figures and the moral question of saving lives, convincing some state leaders to adopt anything under the umbrella of “Obamacare” will be a difficult task this legislative session. Perry must be won over. Even if the Legislature passes a bill expanding Medicaid, Perry could veto it. If Texas is going to expand Medicaid, the governor will have to change his position.

Nearly 50 years after the birth of Medicaid, things are not as dire for low-income Texans as during Johnson’s time. But they’re not much better. In one of the wealthiest states in the nation, more than six million people lack access to health care. Without Medicaid expansion, thousands of Texans will continue to die from treatable conditions.

(Correction: The original version of this story said that Kevin Moriarty ran San Antonio’s Metropolitan Health District. It should have stated that Moriarty worked in San Antonio’s Department of Human Services. The Observer regrets the error).