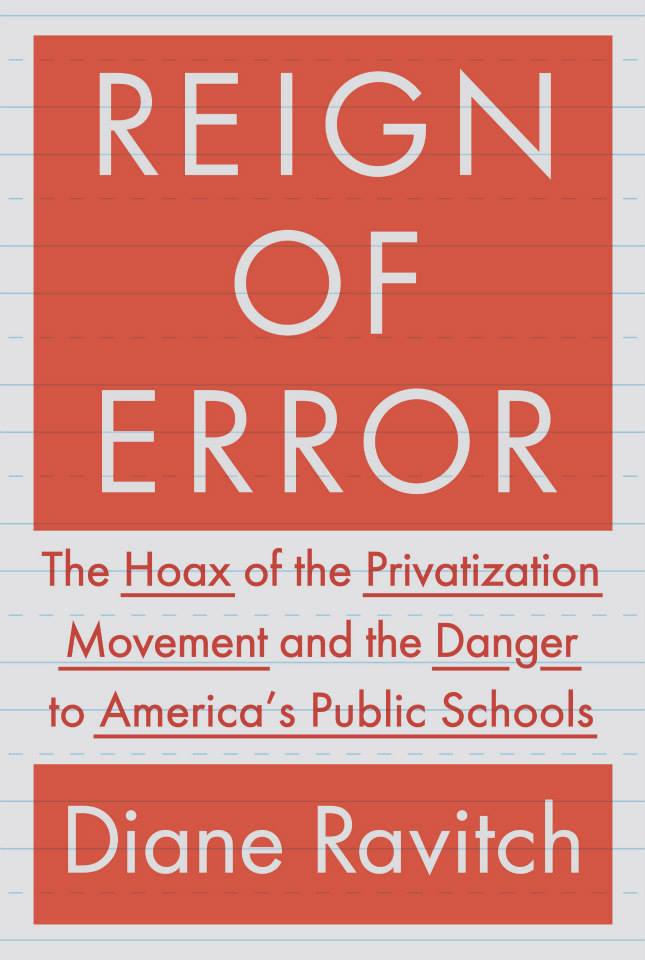

Diane Ravitch Says Public School Reformers Have Got It Wrong in Reign of Error

Above: Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America's Public Schools

By Diane Ravitch

Random House

416 pages

$27.95

A war is being fought that may change the future of public education as we know it. Invective has been spewed and divisions have been drawn. On one side are the self-proclaimed reformers, who push a foreboding narrative: Our public schools are in crisis. U.S. test scores are abysmal, they say. Reformers are quick to blame this decay on incompetent teachers and the unions that protect them, whose failure, reformers say, threatens American economic supremacy, national security, our very way of life.

You’ve inevitably heard or seen this narrative, maybe in the popular documentary Waiting for Superman, maybe on The Oprah Winfrey Show or in Time magazine. After frightening you, the reformers will implore urgency. The system needs an overhaul—right now. Luckily, they have the solution: Judge teachers based on their students’ test scores, fire bad teachers and give merit pay to good ones. Close low-performing schools and funnel public money to privately run charter schools.

The reformers say their disruptive changes will inject free-market efficiency into the public-education marketplace. Their ethos combines the traditionally right-wing concepts of vouchers (public funds subsidizing private-school tuition) and school choice with test-based accountability and charter schools. They season this stew with liberation rhetoric. “Education reform is the civil rights struggle of our time” is a common reformer refrain.

This narrative, according to education historian and Houston native Diane Ravitch, has one problem: It’s dead wrong. In her new book, Reign of Error, Ravitch emphatically refutes the reformer thesis. Public education is not in decline. Graduation rates and test scores are higher than they’ve ever been, and the achievement gap between minority students and white students is closing, albeit slowly. Ravitch spends the first two-thirds of her book carefully examining reformers’ claims, then poking gaping holes in each with statistical and historical evidence.

The reform movement, according to Ravitch, comprises opportunists of all sorts: misguided philanthropists and politicians, financiers out to make a buck, ideologues opposed to public education, and self-promotion artists. Among these opportunists are many of the politically powerful and financially elite, including Bill Gates and Rupert Murdoch, a host of right-wing governors and big-city Democratic mayors, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and President Barack Obama. Education reform proves the old adage that politics makes strange bedfellows.

These reformers anger Ravitch. Her book negotiates that anger by echoing the exasperation of a growing coterie of students, teachers and parents who have coalesced against the reform agenda. In Reign of Error, this group finds its manifesto.

Ravitch excoriates the reformers from a unique position. In addition to being a preeminent education scholar, she served as assistant secretary of education for the first President Bush, and once favored testing and school choice herself. Diane Ravitch is a reformed reformer. What changed her mind? The havoc wreaked by high-stakes testing under George W. Bush’s 2001 No Child Left Behind Act.

According to myth, Bush’s gubernatorial focus on standardized testing and teacher accountability raised test scores in Texas. Boston College researcher Walt Haney has since proved that the “Texas Education Miracle” was more statistical manipulation than reality. Regardless, the federal No Child Left Behind push was Texas-style testing and accountability writ large. According to the law, 100 percent of students would be required to pass standardized state tests by 2014. Schools not progressing toward that goal would be labeled failures and punished. Schools that repeatedly failed would face closure.

Not surprisingly, poor schools serving mostly poor students underperformed. Ravitch explains: “Poverty matters. Poverty affects children’s health and well-being. It affects their emotional lives and their attention spans, their attendance and their academic performance. Poverty affects their motivation and their ability to concentrate on anything other than day-to-day survival.” Despite the abundantly documented correlation between poverty and low test scores, in the eyes of No Child Left Behind poverty might as well not exist.

As schools started to focus intently on tests, other insidious consequences became apparent. “Teaching to the test”—formerly considered poor pedagogy at best, unethical at worst—became commonplace. The all-consuming focus on preparing students to pass standardized tests has narrowed curricula and subverted the purpose and promise of public education as Ravitch sees it: building character and preparing students to become productive, thoughtful and informed citizens.

In 2006 Ravitch realized No Child Left Behind was a failure. She considered the law’s results: poor students often labeled failures, teachers incentivized to avoid high-poverty schools, a rash of schools slated for closure, and no demonstrable school improvement attributable to the law. She recognized that the carrots and sticks of test-based accountability were misguided, but the stage was already set for the reformer narrative.

Ravitch devotes an entire chapter to the most effective peddler of this narrative, former Washington, D.C., schools Chancellor Michelle Rhee. Rhee became a media darling during her three-year tenure in the nation’s capital. Waiting for Superman features her as a take-no-prisoners reformer ready to fix schools by any means necessary. Rhee blamed the low test scores of the district’s predominantly poor students on bad teachers and pledged to make D.C. the highest-performing urban district in the nation. In reality, when she resigned the chancellorship after three and a half years, Rhee left a less-than-glowing legacy. Ravitch summarizes it: “little or no gains on test scores, high turnover of teachers and principals, lowest graduation rate of any big city, largest achievement gap of any big city, a truancy crisis, big increase in spending, a bloated central office staff, and declining enrollments.” To top it off, shortly after Rhee left, USA Today reported evidence of widespread educator-led cheating on standardized tests in the district.

Some say Ravitch paints the reformers with too broad a brush, both in Reign of Error and on her oft-updated blog and Twitter account. Certainly there are reformers who have improved educational outcomes for some students. Many reform supporters are quick to point out the Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) chain of charter schools as an example of reform success. KIPP started in inner-city Houston and, judging by test scores, KIPP schools tend to outperform comparable traditional public schools. But KIPP schools are the exception rather than the rule. And, importantly, KIPP does not take over failing schools and miraculously raise test scores. KIPP starts schools from scratch. They succeed not only because students and teachers work grueling 10-hour days, Saturdays and mandatory summer school—but because of the specific students they enroll. To attend a KIPP high school in Houston, prospective students and their parents must complete a lottery enrollment form and an eight-page “High School Common Application,” and submit a teacher recommendation. Only then will the student be entered into an admissions lottery.

In other words, KIPP benefits from self-selection. The schools effectively serve the most motivated and supported poor students. Add a high rate of attrition among black students—a fact disputed by KIPP but clearly documented by University of Texas professor Julian Vasquez Heilig—and it is obvious that KIPP’s results are not scalable to entire school districts.

If even the best charter schools do not have a solution to the challenge of educating large groups of poor students on a district-wide level, then how can we improve the lives of our nation’s poor children? Ravitch devotes the last third of her book to that problem.

Her proposals—quality early-childhood education for all, medical and social services for needy children, reducing class size and minimizing segregation—aren’t new. They aren’t cheap and easy, nor will they completely eliminate the achievement gap between poor and affluent students. But they have proved effective, they are scalable, and they can help give poor students a fighting chance at success.

Public schools are the bedrock of our democracy, Ravitch writes. “The public schools have made real the promise of e pluribus unum, without sacrificing the pluribus or the unum.” If Americans learn that the current reform movement is more about unfounded dogma and profit motive than improving education, they will fight the privatization of our public schools. Ravitch knows this. With Reign of Error, she exhorts us all to start paying closer attention.

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.