UPDATED: Cuts Threaten Therapy Services for Disabled Texas Kids

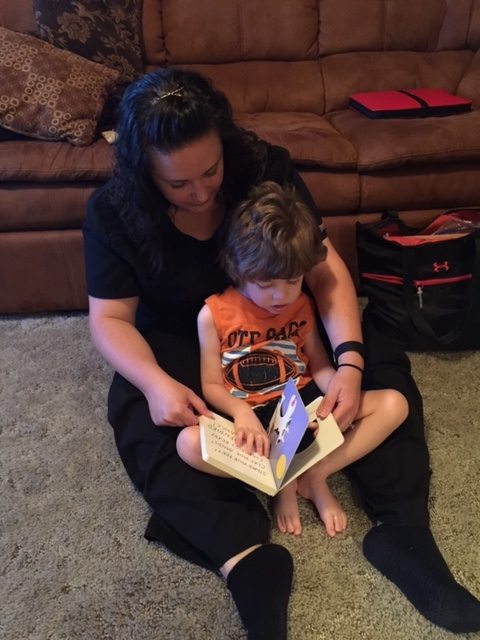

Above: Jaxon Huffman, who experiences spasms and seizures daily, receives in-home therapy services covered by Medicaid. Reimbursement rate reductions set to take effect Sept. 1 threaten services that Jaxon and thousands of disabled children rely on.

Update, August 27, 11:00 a.m.: In an about-face just hours after state officials indicated they would reconsider a proposal to dramatically cut Medicaid therapy reimbursement rates, the Health and Human Services Commission clarified late Wednesday that it is, in fact, moving forward with its original rate reduction plan.

Rachel Hammon, executive director of the Texas Association of Home Care and Hospice, said in a statement that the rate cuts “will most certainly mean the end of acute care therapy for tens of thousands of medically-fragile kids and seniors.

“As we have stated from the beginning, it is impossible to cut the rates by $150 million and ensure medically fragile children and adults will continue to have access to therapy services,” she said. “It is just that simple, a $150 million dollar cut cannot co-exist with access to therapy services.”

As Bob Garrett with the Dallas Morning News reports, the rate cuts could take effect as soon as October 1.

Update, August 26, 11:00 a.m.: Less than a week before the cuts were set to take effect, the state Health and Human Services Commission withdrew its original proposal to reduce reimbursement rates for therapists and providers that serve low-income, disabled children. State officials told a Travis County judge on Wednesday that it would “essentially start over” in following the Legislature’s directive to find ways to save money on Medicaid therapy.

Original post:

Seizures have taken hold of 4-year-old Jaxon Huffman’s body every day for almost his entire life.

At 2 months old, he began experiencing simple partial seizures that interfered with his nervous system and senses. Three months later, his mother Jennifer said, doctors discovered Jaxon was having infantile spasms, a symptom of epilepsy that continues into childhood.

Jaxon has up to 100 spasms and seizures, including several grand mal seizures, every day. His muscles stiffen, his head drops forward or backward. His body temperature may spike or he may choke.

“Different things trigger the seizures: overstimulation in large crowds … certain noises and being in environments that he’s not familiar with,” Jennifer said. “It stresses his little body out.”

Jaxon doesn’t respond to anti-epilepsy medication, and taking him to a crowded hospital or outpatient clinic for therapy would trigger even more seizures and spasms, his mother said. Instead, the family relies on three therapists who each visit their Corsicana home twice a week to help Jaxon cope with his disability.

The speech, occupational and physical therapy that Jaxon receives are all covered by the Texas Medicaid Acute Care Therapy Program, which provides in-home pediatric services for low-income children with birth defects, genetic disorders or cognitive disabilities. Adults recovering from injuries or coping with diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s also use the program.

Earlier this year, the Legislature passed a budget rider directing the Health and Human Services Commission to find ways to save on Medicaid therapy costs. The commission settled on a scheme that would cut reimbursement rates for Medicaid therapy providers that disabled Texans like Jaxon rely on. The cuts amount to a loss of $150 million in state money over the next two fiscal years, and jeopardize another $200 million in federal matching funds.

Rachel Hammon, executive director of the Texas Association of Home Care and Hospice, said home health agencies won’t be able to sustain such a drastic financial hit.

The reimbursement rate reduction “will most certainly impact individuals’ ability to access care,” she said. As many as 60,000 children will bear the brunt of these cuts. The jobs of thousands of therapists statewide are also in peril.

Hoping to prevent the cuts from taking effect, four Central Texas families and five providers filed a lawsuit against the state on August 11, arguing that cutting reimbursement rates “will force Texas Medicaid providers to cease providing services critical to the health and development of Texas’ most vulnerable residents, its children.” Providers also took issue with the fact that the Health and Human Services Commission only held one public hearing on the cuts, as well as the formulas it used to calculate the new rates.

Democratic and Republican lawmakers echoed their concerns. In response, last week the agency revised its original proposal by reducing the size of the first year’s funding cut and spreading the rate reduction across a wider variety of services.

But providers say the effect is still the same.

“If the goal remains to cut therapy by $150 million, the end result will eliminate access to care for the most vulnerable Texans. Rearranging the chairs on a sinking ship may hide the harm, but it does not eliminate it,” Hammon said in a statement. “This new proposal should also be subject to a hearing so the public, therapy providers, and families impacted by the cuts can provide evidence to HHSC what the new rates will mean to access to care.”

For many families in Texas, including the Huffmans, Texas’ Medicaid therapy services are the only way their disabled children can get the help they need. For Jaxon, that help means being able to enjoy his food like any other child.

Until recently, the Huffmans took Jaxon to the hospital two to four times a year for respiratory infections. Sometimes they would stay for days, racking up hospital bills as high as $50,000, and requiring Jennifer or her husband Bill to take time off work.

Then, in January, the speech therapist who visits their home twice a week hypothesized that Jaxon might be aspirating his food, which would explain the infections. Doctors confirmed the theory, but when they proposed giving Jaxon a feeding tube, Jennifer panicked.

“My child can’t walk, talk, he can’t sit up, he has little head control. The only thing that he really enjoys is Mickey Mouse and his food,” she said. “It was devastating for us as a family to hear that kind of news for our child.”

Jaxon’s speech therapist suggested VitalStim therapy, which involves various techniques to stimulate the throat muscles and help patients swallow. Since starting that therapy in January, Jennifer said, Jaxon hasn’t been back to the hospital for a respiratory infection. She worries about what will happen if the cuts take effect.

“There’s no way that we could perform VitalStim therapy” without Jaxon’s therapists, she said. “He’d have to have a feeding tube, and we’ve had to either hire a [full-time] nurse or we would have to quit our jobs. We both work because that’s the only way that we can support our family and children.”

The cuts are still scheduled to take effect Sept. 1, but the lawsuit may change that, according to an agency spokesman.

Until then, Jennifer hopes state officials will find other ways to save money rather than cut funding for services her family depends on. “It took us so long to get any help,” she said. “Now, I feel like now they’re just going to take it away.”