Freedom Fighters

Dallas has freed more innocent men from prison than any other county in the country. Now they’re working together to change the system.

On May 12, Johnnie Pinchback became the 28th Dallas man to be freed from prison after evidence proved police got the wrong guy.

I spoke to him the day after he got out. He was so happy to be free he hadn’t slept yet. “I’m on my way to my sister’s house, to eat catfish,” Pinchback said in a giddy tone, like he couldn’t believe he was doing something so normal. “I feel marvelous. Just being able to breathe. Just to hear the mockingbirds sing.”

Pinchback spent 27 years behind bars for the rape of two teenage girls, who misidentified him in a police lineup. He was released after the Innocence Project of Texas took up his case and DNA evidence proved he wasn’t the perpetrator. Pinchback likely wouldn’t be free if it weren’t for help from other Dallas exonerees released before him. They not only provide proof of how the system can go wrong, but also have organized into a potent grassroots force for freeing other innocent men.

Since 2008, fellow Dallas exoneree and innocence activist Charles Chatman has been lobbying for Pinchback’s release. “When he got out, it felt almost as good as when I got out,” says Chatman, who was also incarcerated for 27 years for rape because of mistaken identity.

Chatman and Pinchback were housed at the Coffield Unit southeast of Dallas and became best friends after Pinchback arrived in 1984. Pinchback says Chatman was “like my brother. We worked the fields together. We had each other’s backs.” Chatman doesn’t remember ever talking about the most significant thing they had in common—they were both wrongly convicted. “It’s just a normal thing in prison,” he said. “If you are in for a hideous crime like rape, you don’t talk about it. If other prisoners find out, you’re subject to beatings and rape. You don’t broadcast that.”

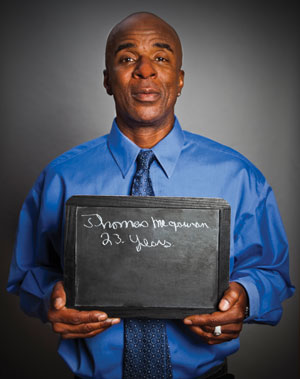

Chatman often goes to greet other exonerees when they’re set free. At the release of Thomas McGowan, pictured left, in 2008, a woman approached Chatman to ask if he could help with her father’s case. It was Johnnie Pinchback’s daughter. “Knowing what kind of guy Johnnie was, I was interested,” Chatman said. “But I didn’t work to get him freed just because he was my best friend. I went down to the unit to talk to him. I told him if he had anything to do with the case—even if he was just the lookout—I couldn’t help him. He looked me in the eye and told me he didn’t have anything to do with it. After all those years I spent in prison, I have a pretty good idea when someone’s lying. I just felt it in my body that Johnnie was telling the truth.”

Chatman went to the Innocence Project of Texas, which had already received a letter from Pinchback. There were hundreds of other cases in line to be investigated. “I asked them to review the case, and they did,” Chatman said. “They know me and know I wouldn’t bring them the case of someone trying to trick the system. That was my role, but the Innocence Project deserves the full credit for getting him out.”

The day Pinchback was released, Chatman and a dozen other Dallas-area exonerees were there to greet him. Chatman said he wanted to help Pinchback get new glasses, clothes and an ID. “Parolees have a reintegration program, but we don’t have that,” said Chatman. “Johnnie will get compensated. But in the meantime, he’s staying with his mom, and he needs some help. But we have the exoneree group here; we’re the only city that has that. We’ve been through it. We know what he needs. We’ll help him pay the bills and make sure he doesn’t eat up all his mom’s food. That’s what we do.”

Pinchback says he won’t soon forget the help. “When Charles visited me in prison, he told me, ‘We’re gonna take care of this,’” Pinchback said. “And he said, ‘All I ask is that you help others out when you’re released.’ And that’s what I’ll be doing.”

Three days after being released, Johnny Pinchback attends services at the Greater Peoples Missionary Baptist Church in Dallas. Friends and family surround him, including fellow exoneree Charles Chatman, bottom left.

There have been more prisoners freed in Dallas than in any other region in the country, and it’s created a snowball effect. The freed men have created one of the most powerful grassroots criminal justice reform organizations in the state. These men are changing the way investigations are done in Texas.

The Texas Exoneree Project, as the Dallas group calls itself, began with a humble mission—the group provided a space for exonerees to help each other meet their needs. The Project has moved far beyond that. A few weeks before Pinchback is released, there’s a full agenda at the monthly meeting, held in a bright conference room at the Holy Trinity Church in Dallas. At the table is the group’s director, Texas A&M-Commerce social work professor Jaimie Page, and eight exonerees, a smaller group than usual because it’s Easter weekend. Most of the exonerees are debonair in dress shirts and fedoras, as if to make up for the years of white jumpsuits. All of them are black and middle-aged. Between them, they’ve spent around 150 years in prison.

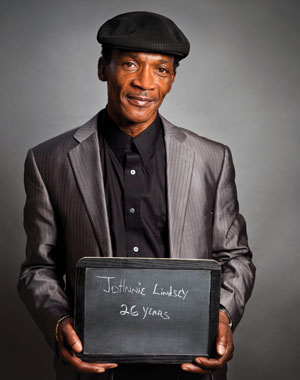

At today’s meeting, the exonerees discuss going down to Austin for the fifth time this session to lobby the Legislature for bills reforming eyewitness procedures and getting health care for exonerees. “We have a lot more impact if they can put a face to the story,” said exoneree Johnnie Lindsey. They plan to write a pamphlet to help other exonerees through the transition, with topics that include technology, getting to know family again, uniting with other exonerees. They talk about innocence cases they are fighting for, including Johnnie Pinchback and two other men who are free but have not been officially declared innocent. This is a situation some exonerees find themselves in when the evidence remains murky or for other reasons, as in the case of Anthony Graves, who was released from jail without being declared “actually innocent.”

The group’s newest member is in this situation. Larry Sims has recently been freed after being jailed for 25 years for rape. His is an odd case where it looks like a crime might not actually have occurred at all. The state has released him after a DNA test showed that his cousin had sex with the alleged victim that night. (The cousin testified to that effect in the original trial, but the alleged victim denied it.) This fact convinced the judge that Sims had not received a fair trial, and he was released. Unlike the other Dallas exonerees, however, Sims was not found “actually innocent,” a designation that would allow him to receive compensation from the state. His case is now before the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. If the court doesn’t rule him innocent, Sims is going to be starting life over at 60 years old, without a dime to his name.

“Is it against the law to get exonerated in Dallas County? They’re fighting so hard. They are wasting tax dollars,” Sims says, his voice shrouded in bitterness.

“You’re mad,” says Billy Smith. He also spent two decades in prison for a rape he didn’t commit. “You’re not going to beat them mad. You need to sit back and let your attorneys do their work.”

From there, the meeting evolves into a nuanced discussion about how to change the law so more exonerees are given “actual innocence.” The Dallas exonerees do their best to help each other, but they keep their eyes on the prize—changing the system.

These men have been freed because Dallas now has a district attorney, Craig Watkins, who’s eager to open innocence cases, and because the Dallas County medical examiner had the foresight to store decades worth of forensic evidence that can be tested for DNA. Very few, if any, other counties in Texas have a system like Dallas’s, making it difficult, and often impossible, for them to locate older evidence. Another reason so many have been freed is a long legacy of flawed police policies, coupled with Texas-style, tough-on-crime prosecutions. Under District Attorney Henry Wade—who served from the ’40s to the ’80s and is the Wade in Roe V. Wade—the Dallas DA’s office built a reputation for going hard after convictions. Wade himself never lost a case as prosecutor, and his office had conviction rates of over 90 percent. “The mentality was win at all costs,” says John Stickles, a defense attorney who helped found the Dallas exoneree group. “The thinking was, ‘If he’s been arrested and indicted, then we’re going to convict him.’”

As Wade-era exoneree Johnnie Pinchback puts it: “If you didn’t cop out, you got big times. That’s the way it was.” Pinchback says he was offered a 15-year plea deal. When he refused to confess to a crime he didn’t commit, the judge came back with 99 years.

This philosophy persisted after Wade left office in 1987. The theme that runs through almost every exoneree’s case is a reliance on eyewitness identification at the expense of other evidence. Police and prosecutors know that if a witness identifies his or her assailant, that’s all they need to make a powerful impression on the jury.

But human memory is susceptible to manipulation. Add to that the fact that the witness identification methods formerly used by the Dallas Police Department—and still used in many places—were deeply flawed. “Police lineups could be very suggestive,” says Dallas DA Watkins. “For instance, if the perpetrator was described as having a blue shirt on, then the police’s main suspect would be the only person in the lineup with a blue shirt.”

Police would show witnesses what’s known as a ‘six-pack’—six mug shots arranged on a page—and ask victims which one most resembled the perpetrator. It’s not surprising that victims would compare the photos and then pick the one that most resembled the attacker, even if they weren’t sure. Once a perpetrator is chosen, research shows that victims will insert the new face into their memories of the crime, becoming more sure of their choice over time.

Watkins has changed the way Dallas police gather eyewitness identifications. They now use a “double-blind” method in which the officer administering the lineups is not involved in the investigation and is not aware of the suspect’s identity. This prevents the kinds of suggestive remarks that have led to false identifications in the past. Witnesses are now shown photos one by one, to prevent picking the one who happens to most resemble the perpetrator. “It’s a work in progress,” said Watkins. “There might be a better system in five to 10 years. If we notice flaws, we have to be willing to make progress so the system works as it should.” Watkins and the Dallas exoneree group are backing legislation that would require that every county DA office in Texas implement a system for eyewitness identification.

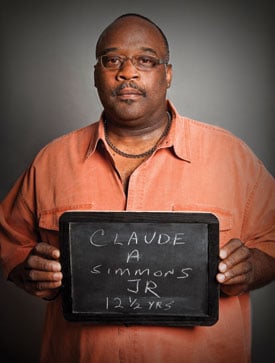

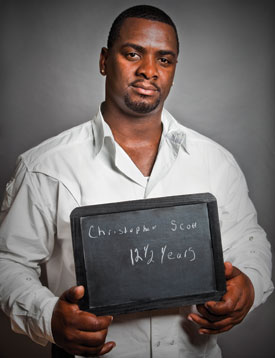

Many false convictions are honest mistakes, but in some, the process is so flawed you have to wonder whether justice was ever the motive. Take the case of Christopher Scott and Claude Simmons, two members of the Texas Exoneree Project who were exonerated in 2009 after serving 12 years for capital murder. One night in 1997, Simmons wanted to get out of the house and invited Scott out to talk. On the way back home, Scott drove by the scene of a murder. A man named Alfonso Aguilar had been shot during a robbery in front of his wife, Celia Escobedo. The police followed Scott home, handcuffed him and took him to the police station—though he didn’t match Escobedo’s initial description. “They took me downtown and handcuffed me to a bench,” he recalls. “And they brought [Escobedo] to me, and it sounded like the police said, ‘This is the man who killed your husband?’ I couldn’t quite hear how she responded. I’m thinking, ‘I know she didn’t say what I thought she just said.’ But I knew it was bad because she was crying hysterically.”

Many false convictions are honest mistakes, but in some, the process is so flawed you have to wonder whether justice was ever the motive. Take the case of Christopher Scott and Claude Simmons, two members of the Texas Exoneree Project who were exonerated in 2009 after serving 12 years for capital murder. One night in 1997, Simmons wanted to get out of the house and invited Scott out to talk. On the way back home, Scott drove by the scene of a murder. A man named Alfonso Aguilar had been shot during a robbery in front of his wife, Celia Escobedo. The police followed Scott home, handcuffed him and took him to the police station—though he didn’t match Escobedo’s initial description. “They took me downtown and handcuffed me to a bench,” he recalls. “And they brought [Escobedo] to me, and it sounded like the police said, ‘This is the man who killed your husband?’ I couldn’t quite hear how she responded. I’m thinking, ‘I know she didn’t say what I thought she just said.’ But I knew it was bad because she was crying hysterically.”

listen to an excerpt from Christopher Scott’s interview

This was not proper eyewitness identification procedure—there wasn’t even a lineup. Once the police had the identification sewn up, they stopped looking for other suspects, though they couldn’t find any corroborating evidence to implicate Scott. There was no gunshot residue or blood on his clothes, his tire tracks or fingerprints were not at the scene of the crime, and none of the stolen items was in his possession. A week later, police picked up Simmons and indicted him as an accomplice.

Scott’s court-appointed lawyer met with him once before the trial. “I couldn’t have gotten a fair trial,” Scott says. “Listen, I’m not a racist. But I had 12 white jurors, a white judge, a white prosecutor, a white lawyer. I was the only black person in the courtroom. When I walked in, I knew I was going to be found guilty. That’s just how the stage was set.”

When the judge asked Scott why he should spare his life, Scott said, “Because you don’t want to execute an innocent man.” Scott and Simmons were given life in prison.

Once Simmons and Scott were found guilty, the lack of evidence turned into a liability to their efforts to free themselves. Unlike the cases of other Dallas exonerees, there was no DNA evidence available to prove their innocence. “A prison lawyer told me I had a one-in-a-million chance of getting out,” Scott said. “That’s when I turned to God. All us exonerees talk a lot about God. Because when men have failed you, what else do you have? You have to believe in a higher power than the guys who did this to you.”

Around 2005, a prisoner named Alonzo Hardy confessed in a letter that he and another man killed Aguilar. The state ignored his confession. In 2007, Scott and Simmons got a break. Dallas voters elected Watkins, the county’s first African-American district attorney and the first one who hadn’t come up through the ranks of the prosecutor’s office. Shortly after entering office, he created the Conviction Integrity Unit, whose sole job is to investigate wrongful convictions.

“I had trepidations about it when I was newly elected,” Watkins says. “But it was the obvious thing to do. And we’ve gained credibility with the community by doing this. We’ve proven we’re willing to look at the past. And it makes it easier for our young lawyers to present a case. The public knows that we’re not going to bring a case to trial unless we emphatically believe in their guilt. I’m trying to figure out why other DAs in Texas criticize it. We have to have policies to police ourselves. And because of our approach, our conviction rates are up.”

The Dallas Conviction Integrity Unit took up Scott and Simmons’ case and eventually brought Hardy in for a deposition and lie detector test. The lack of DNA evidence in the case made exoneration difficult—and it was a potential political liability for the DA. (Before the 2010 election, Watkins’ political opponents tried to spin the case to make it look like Watkins had let two killers loose. Watkins calls the smears the typical “Southern strategy.”) Despite the risk, the DA’s office took up the investigation, repeatedly interviewing the confessed killer about the crime to be sure he wasn’t making it up. Finally, in 2009, after 12 years in prison, Scott and Simmons were freed. They’ve inspired other prisoners who don’t have DNA evidence to prove their innocence. “They say, ‘We didn’t have any hope, but now you’ve paved the way,” Scott says.

When Scott and Simons saw each other in the courtroom the day they were exonerated, it was the first time in 12 years. “I looked at him and said, ‘I’m staying away from you when I get out!,” Scott says. “But really, it’s a lot of love. We talk three or four times a week about what’s going on, the struggles we’re going through.” The Texas Exoneree Project got two more committed members.

The Texas Exoneree Project began as a focus group convened by Page and Stickles in late 2008. “I looked at their cases,” Page says. “And it was so egregious how they’d been set up. I felt as a citizen, I needed to do something. We’re the ones who elect these prosecutors.”

When the group first got together, many of the exonerees had not received compensation yet from the state and were living hand to mouth or off loans from their attorneys. They started a list of things they would ask of legislators, like $5,000 upon release for housing and transportation, and access to services like mental health care and job training. (In 2009, the group lobbied the Legislature for these services and helped pass a bill that increased their compensation, and gave them job training and money for college tuition, as well as some counseling and help accessing health care.)

For Christopher Scott, the hardest part of his transition was a simple thing most of us take for granted: getting a state ID. He didn’t have access to the documents he needed to get one. “For the first five or six months, I didn’t have a Texas ID,” he recalled. “You have no means of saying you are who you say you are. It’s like being a ghost.” Scott got a support letter from Page and others, and finally got an ID.

The group gets together to discuss less-tangible things as well, things that only other exonerees understand. As happy as exonerees are to have their freedom back, most still suffer from a form of post-traumatic stress disorder. “I just think, ‘I can’t believe I got convicted for something I didn’t do,’” says Keith Turner, an exoneree who suffers from PTSD after spending four years in prison. “And that’s where it starts. It’s something you won’t ever forget. You just go to deal with it. So when I need someone to talk to, I can turn to the other guys here.”

The transition comes with some unresolved emotions. Johnnie Lindsey was in prison for 26 years. He says after the first decade, no one from his family wrote or visited him, and that makes it hard to reconnect. “When I needed someone the most, they weren’t there,” he says. “The worst reply was, ‘you must have done something or they wouldn’t have locked you up.’ But no one spent the time finding out what I had supposedly done. So you live with this, year in and year out. And these things are constantly going through your mind. When you get out, you’re looking around, thinking, ‘Who can I trust?’ One way the group helps is that I know there are people I can call who share the same emotions, the loneliness and the hurt.”

listen to an excerpt from Johnnie Lindsey’s interview

Lindsey echoes a familiar theme among the exonerees I spoke with. His family abandoned him when he was in prison, he says, and then showed up as soon as he got his compensation check, asking for a piece. Exonerees now get $80,000 for every year they served behind bars, plus another $80,000 per year paid out in an annuity. With exonerees like Lindsey, who have been in for decades, the compensation equals millions of dollars. Lindsey’s mantra when family come asking is “Just Say No,” something he’s helped other exonerees do. “It’s put some strain, where family is concerned,” he says. “For a while, one family member stopped talking to me period. But I don’t feel bad about saying no. All I owe them is love and respect. If they get upset with that—they went off for 26 years, they can go off for 26 years more.”

The group also helps protect its members from shady businessmen, lawyers and investment advisers who want to con exonerees. “If someone tries to take advantage of one of us,” says Scott, “then we’ll call the others and tell them, if this individual or organization calls you, feed them with a long-handled spoon, because they mean you no good.

“And don’t rush to get married,” Scott continues. “That’s the No. 1 rule. You lost so many years in prison, don’t fall victim to the first woman you run across. And if you do get married, get a prenup. There’s a lot of wolves out there.”

Exonerees don’t always agree on who the wolves are, which has caused some tensions. When the group first convened, several exonerees were represented by Kevin Glasheen, who was financially supporting several of the men. Glasheen started sending a lawyer to every meeting. He says he was worried about what other lawyers or investment advisers Page was bringing into the group, and what exonerees were discussing. “She could unwittingly create evidence that could be used against these clients by discussing their issues in a group,” wrote Glasheen in an email.

The tension came to a head at a meeting when Glasheen’s representative did not show up. Page had heard that Glasheen was insisting that compensation checks be sent to him, and he would take his fee before forwarding the money. That didn’t smell right to Page. “I said that the compensation should be sent to you,” she says. “And then you can pay his invoice. I told them they should control their own money. I also let them know they could get a second opinion from another lawyer.”

That conversation got back to Glasheen. “He told an exoneree to tell me that if I didn’t call him, he was going to sue me on Monday,” says Page. “I said, ‘I won’t call him. I don’t work for him. They can do what they want to me. I’m ready.” For his part, Glasheen wrote in response to the Observer’s questions that his fears were reasonable. “If Jaime Paige and another lawyer work together to induce our clients to break their contracts, then they could be liable for tortious interference with contract.”

That conversation got back to Glasheen. “He told an exoneree to tell me that if I didn’t call him, he was going to sue me on Monday,” says Page. “I said, ‘I won’t call him. I don’t work for him. They can do what they want to me. I’m ready.” For his part, Glasheen wrote in response to the Observer’s questions that his fears were reasonable. “If Jaime Paige and another lawyer work together to induce our clients to break their contracts, then they could be liable for tortious interference with contract.”

Regardless of who was right, Page says the conflict divided the group. “The conflict was noticeable,” says Charles Chatman, who was represented by Glasheen. “I don’t understand why he threatened to sue her. Look, a lot of people think we are walking money signs. But I’ve never seen that in Ms. Page, and I’ve looked for it. I’ve got nothing but good things to say about her.”

Nevertheless, the conflict threatened the stability of the group. “It brought back a certain prison mentality,” Page says. “There were ramifications for the ones who told Glasheen what I said—others felt they were snitches. I didn’t feel that way. I felt they were exploited.” (Glasheen remains controversial. Two of the Dallas exonerees recently sued him over fees he charged for lobbying at the Capitol. Others have agreed to pay him.)

Page had to remind the group to come together over what they had in common. The group helped pass the 2009 compensation increase, but it did not apply to exonerees who had already settled with the state. That means that some in the group are millionaires, and others are living in small apartments with their family. One member, Wiley Fountain, has spent years living on the street and struggling with alcohol addiction. He needs regular attention from the others. “After the payouts, I saw a separation developing in the group,” says Page. “For instance, the exonerees who got larger amounts bought houses, and then asked if we could start holding meetings in their homes. A couple of the exonerees who got less thought they wanted to show off. It wasn’t true—it was about making the meetings more social.”

Page says these issues have worked themselves out. “Now we keep focused on the battles we’re fighting,” she says. “We speak with a common voice, and everybody wins.”

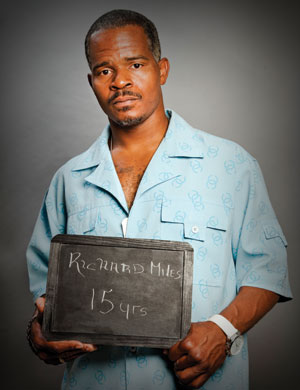

Exoneree Richard Miles speaks to students at W.H. Atwell Middle School in Dallas about his case and the time he spent behind bars. He hopes to encourage students to stay in school and avoid prison.

On May 10, a couple of days before the deadline for the Texas House to pass bills, two exonerees are at the Capitol for a press conference and a final push for the legislation they’ve rallied behind. For Charles Chatman, this is his fifth time in Austin this year to lobby for legislation. One of the bills, sponsored by Sen. Rodney Ellis, a Houston Democrat, would require Texas law enforcement agencies to implement eyewitness identification policies based on proven best practices, like those in Dallas. “We are not trying to just get people out, but we also want to stop innocent people from going in,” Chatman says. “I want legislators to see and hear from us, because wrongful convictions are still happening today.”

Another bill sponsored by Ellis would require that DNA testing be done in all situations in which it could prove innocence. Ellis, who has worked with the exonerees on several bills, says having exonerees lobbying for these bills is essential. “It’s made a tremendous difference,” says Ellis. “It puts a face on the problem and has sensitized my colleagues to the human suffering caused by wrongful convictions.”

Ellis has also sponsored a bill that would allow exonerees to buy health insurance from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. Many exonerees enter prison as young men, but come out with prison diseases. Chatman says he can’t get health insurance because of pre-existing conditions. “I went in young and healthy,” says Chatman, “and came out with high blood pressure and borderline diabetes.”

The exonerees’ efforts paid off. All three of the bills they lobbied for passed both chambers of the legislature: the exoneree health care bill, the eyewitness identification policy bill and a bill that would require post-conviction DNA analysis in cases where there was physical evidence that hadn’t already been properly tested. The three bills are now headed to Gov. Perry’s desk for his signature.

Back in Dallas, the exonerees are coming up with a more hands-on approach to getting innocent men out of prison. Christopher Scott is organizing an effort to outfit exonerees with private investigator licenses so they can work innocence cases on their own. “I want to help guys that can’t help themselves,” Scott says. “I couldn’t help myself. I could only write to organizations, and they all turned me down. If you get someone to write and say, ‘I’m looking into your case.” You don’t know how that makes a man feel. It’s like having a brand new beautiful baby.”