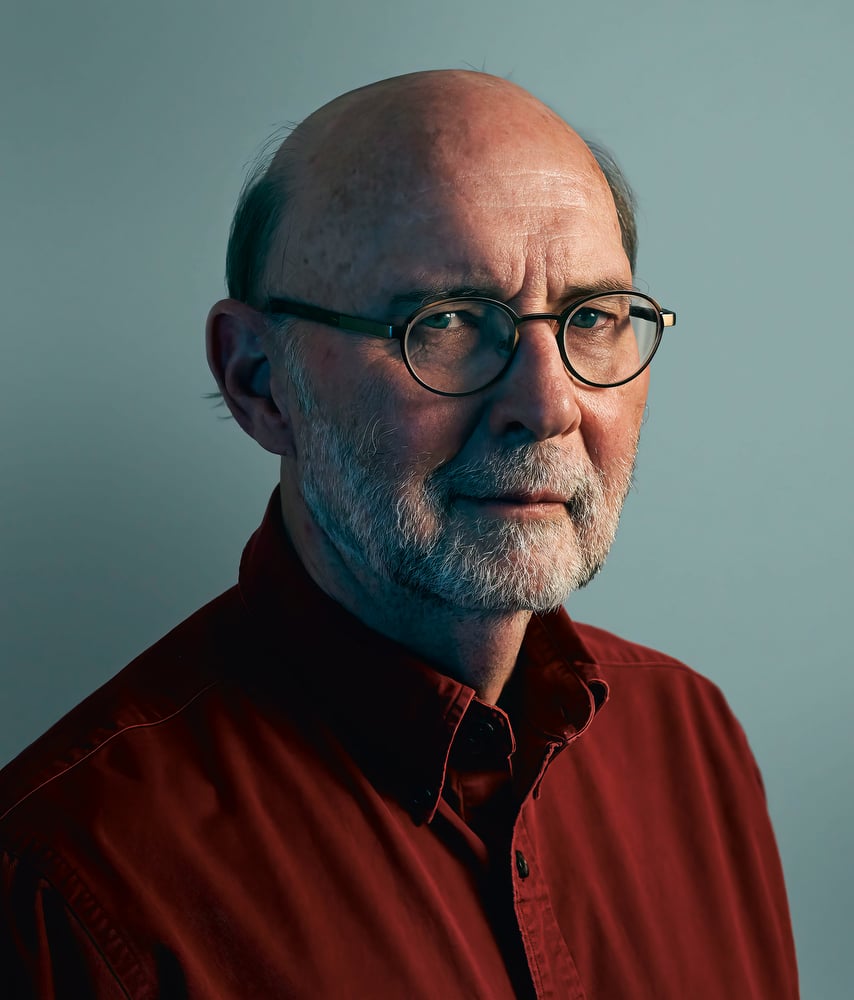

Jim Moore Calls For The Texas Tribune to Distance Itself From Funders

A version of this story ran in the May 2014 issue.

Jim Moore—the ballsy writer behind the Karl Rove takedown Bush’s Brain—began tarring The Texas Tribune early this year, and the fallout is lingering.

On his own site and in The Huffington Post, Moore writes that the Tribune has a history of being too aggressively cozy in courting the powerful interest groups that also happen to fund it.

Moore makes the case for guilt by association, and argues that the Tribune needs to distance itself from philosophical or even physical proximity to the folks giving it money. He might not have proved that the Tribune’s reporting is sullied by the money it receives, but he sure suggests that readers can’t be faulted for noticing a perception problem.

Since former Texas Monthly editor Evan Smith co-founded the nonprofit online publication in 2009, the Tribune has employed some of the finest, most ethical reporters in the nation. Investigative Reporters and Editors just honored the Tribune with an award for “innovations in watchdog journalism.”

Even so, according to Moore, “Smith has created a kind of carnival barker approach to news and sidling up to power brokers and the wealthy … The Texas Tribune he built is cancerous and must be euthanized. If a new version is born, it must have new leadership.”

This isn’t the first time questions have emerged. The Observer pointed out in 2012 that billionaire T. Boone Pickens and Smith performed a series of “road shows” together, set against the background of Pickens’ $150,000 contribution to the Tribune.

All news outlets deserve such scrutiny. When the late Waco insurance man Bernard Rapoport gave money to the Observer (the Rapoport Foundation still does), critics thought he was paying to advance his own socialist-liberal agenda. When I worked at The Dallas Morning News, the paper was accused of bowing to major advertisers like Neiman Marcus.

Since Moore’s attacks, Tribune editor Emily Ramshaw has been eloquently defending her publication, and writing about new ways the Tribune will let readers know who funds it. “We hope,” she wrote on the site, “these new standards … will make us the most transparently funded news organization in the country.”

Here is one example of the painstaking new full-disclosure policy, affixed to a recent story about the donors supporting Gov. Rick Perry’s national marketing of Texas to business:

Disclosure: Paul Foster was a major donor to The Texas Tribune in 2011 and 2013. Western Refining, where Foster serves as chairman of the board, is a corporate sponsor of the Tribune. Bruce Bugg is chairman and trustee of the Tobin Endowment, which is a major donor to the Tribune. The University of Texas at Austin is a corporate sponsor of the Tribune; Southern Methodist University was a corporate sponsor of the Tribune in 2013. A complete list of Texas Tribune donors and sponsors can be viewed here.

Donations don’t necessarily equal influence, but in the end it doesn’t matter whether perceptions about a publication are driven by innuendo or facts. Perceptions are shaped regardless, because news consumers are more skeptical of the media than ever.

One big-time Texas lobbyist-consultant, someone so deep inside the statehouse he can touch its cold heart, told me in an interview that public perception of the Tribune is defined primarily by Smith, whom he christened “the new Cactus Pryor.”

Cactus Pryor was the legendary Austin broadcaster who morphed into the most ubiquitous of media figures in Texas, the “go-to” guy when politicians needed a roastmaster, or when a chamber of commerce needed someone to induct a Big Shot into the local Hall of Fame.

Smith is running a serious news organization, not a rent-an-emcee service, but the brouhaha isn’t going away if someone at the core of the state’s political firmament sees him as an omnipresence hopping on stages with the powers-that-be.

The conundrum points to how fine a line the brave new world of nonprofit journalism has to tread in the search for viable business models. Access to the state’s heavy-hitters can put readers close to important news and sources. But the perception of favor toward those same heavy-hitters is an obvious pitfall. Readers might begin to wonder what really happens when you dance too closely with the bigwigs what brung ya. And that’s when image can start to overshadow all of that hard-earned journalism.