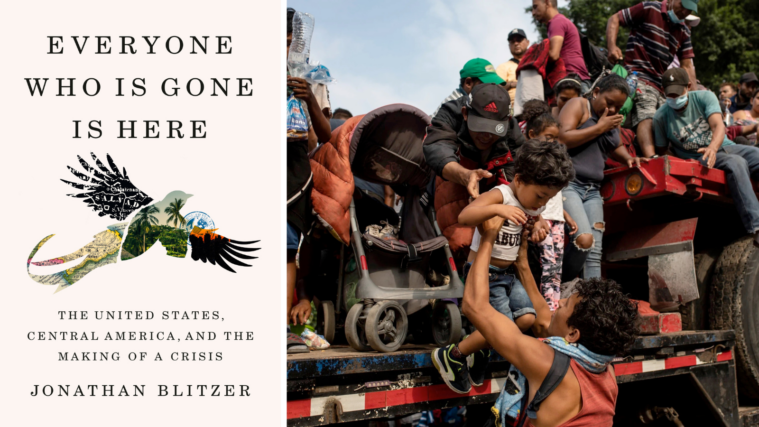

Captive Genius

From the isolation of a psych ward, Mexican immigrant Martín Ramírez became a 20th century master.

A version of this story ran in the February 2016 issue.

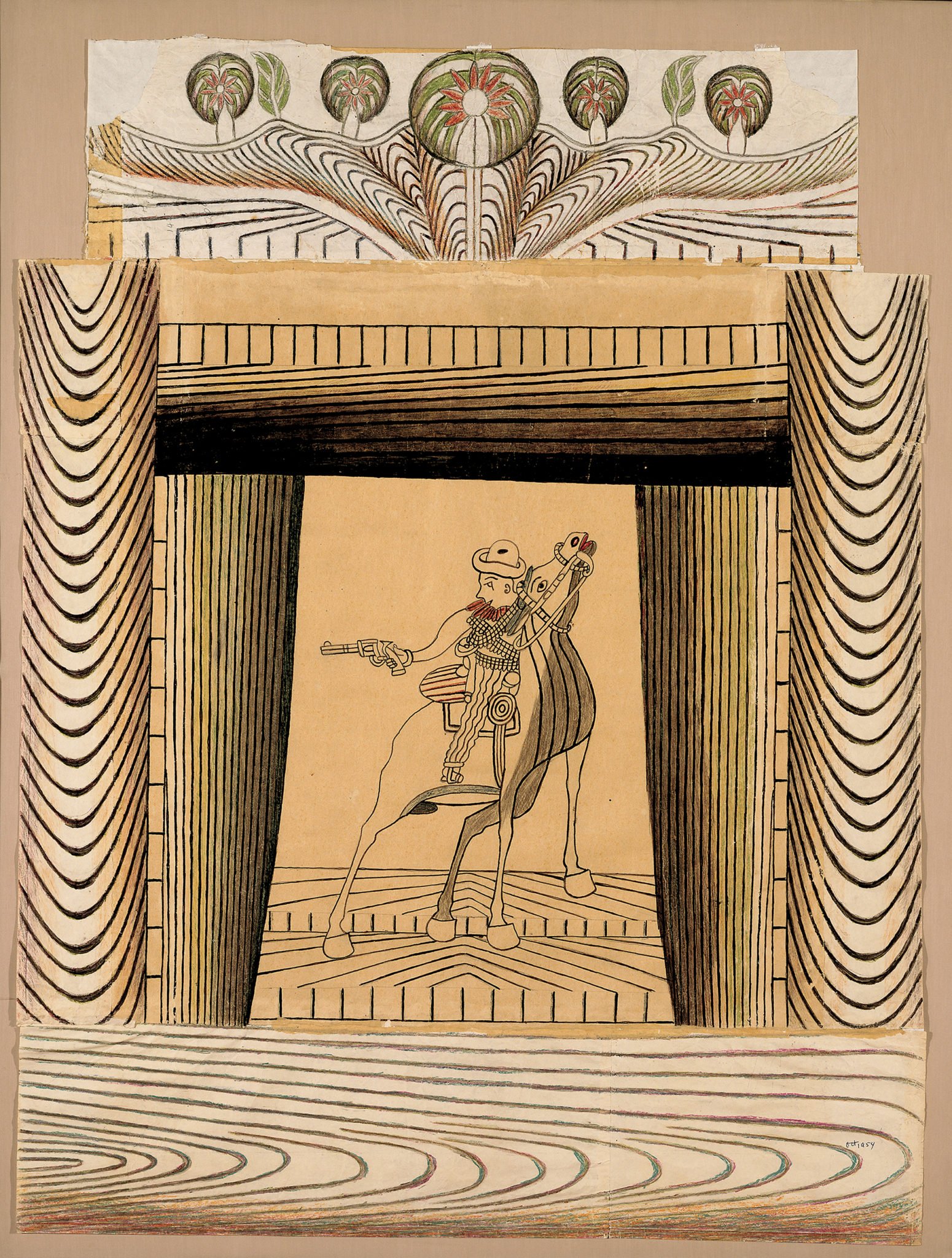

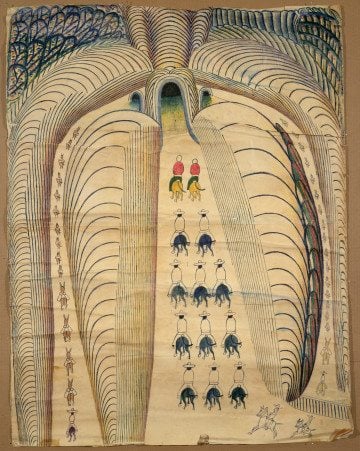

Above: Martín Ramírez, untitled, c. 1954. Crayon and pencil on pieced paper.

In the 32 years Martín Ramírez spent committed to psychiatric hospitals, he drew hundreds of pictures on scraps of paper glued together that today are worth, collectively, tens of millions of dollars. Diagnosed as a schizophrenic and described, variously, as mute and “retarded,” Ramírez drew pictures of his home in Jalisco, Mexico, and of the trains that were part of his immigrant experience. While institutionalized in the 1950s, he was visited by Tarmo Pasto, a professor of art and psychology who helped organize exhibits of what Pasto described as a nexus between psychosis and art. Ramírez’s pictures, exhibited alongside the work of masters, were still designated “outsider art,” the baffling, brilliant production of people otherwise relegated to the fringes of societies. More recently, one of his drawings became part of the permanent collection of New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, and as the New Yorker wrote in December, Ramírez, Bill Traylor and reclusive hospital custodian Henry Darger “now verge on the status of modern masters.” Ramírez’s story is told with academic precision by Victor Espinosa in Martín Ramírez: Framing His Life and Art, and excerpted here with photos of his hauntingly beautiful work. —Nancy Nusser

In 1925, like thousands of Mexicans, Martín Ramírez went to look for work in the United States, leaving his wife and children at home in a small rural community in Mexico. Many Mexican migrants, after a few years of work in the mines, on the railroad, or in the fields, returned to their homes with some savings. Those who stayed longer soon lost their jobs as a result of the Great Depression and were forced out of the United States. The case of Ramírez was different. In January 1931, at the age of thirty-six, he was detained by the police in Stockton, California, emotionally upset and in very bad physical condition. After a medical evaluation, he was diagnosed with chronic depression and interned in a crowded psychiatric hospital. After spending several months under observation and unaided by an interpreter, he was diagnosed as a catatonic schizophrenic. During the clinical evaluation, he limited himself to simply repeating that he did not speak English and that he was not mad. In those years, for somebody in his situation, his diagnosis meant a life sentence. He was never released. After thirty-two years of seclusion, he died in 1963 at the age of sixty-eight.

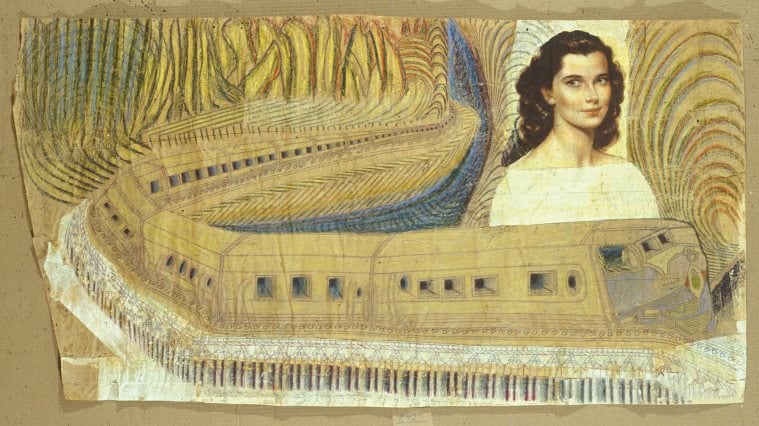

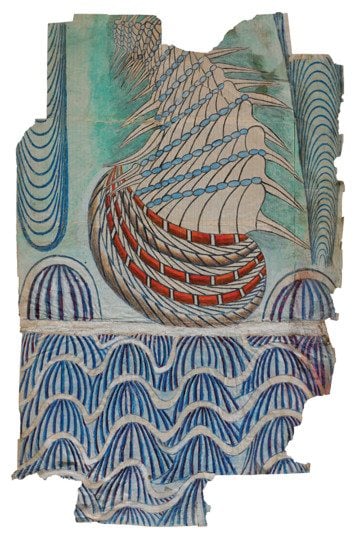

Ramírez might have been completely forgotten, like many Mexican migrants who died during their journeys and never returned home to their families. Yet he was saved from anonymity because after several attempts to escape from the psychiatric hospital, he began to draw obsessively. He worked every day, crouched on the floor over enormous sheets of paper he constructed out of scraps. He patiently glued together the paper he received from the hospital, along with any he found in the garbage cans, using glue he made by mixing saliva with potato. His art materials consisted only of pencils, crayons, shoe polish, red juice extracted from fruits, the charcoal from used matchsticks, and a paste he made by mixing some of the raw materials with oatmeal, his own saliva, and even his own sputum. Other than working on his drawings, Ramírez demonstrated no other interests and did not participate in ward activities; and perhaps because he was able to speak only very little English, he seemed uninterested in talking to other patients. Apart from the time he spent eating, Ramírez dedicated himself only to smoking and producing, according to his doctors, a copious amount of Egyptian-type art. The exact number of drawings that Ramírez completed during his life is unknown: many were destroyed by the personnel of the two hospitals where he was confined. The four hundred fifty or so drawings known to exist today were collected and preserved by two men: a Sacramento painter and professor of art and psychology who sporadically provided him with paper, pencils, and crayons, and the physician in charge of the ward where Ramírez was secluded during the last years of his life.

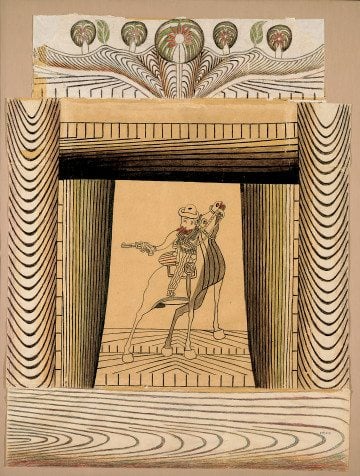

The content of Ramírez’s drawings shows that he was driven by a strong need for expression, communication, and recognition. His work is filled with nostalgic scenes of his life in Mexico, including recognizable churches of the towns where he lived, local religious icons, the rural landscape, laborers, common fauna of Mexico, his own domestic animals, people dancing, men making music with a violin and a guitarrón, scenes of bullfighting, and, especially, horsemen and horsewomen. The content of his work suggests that drawing became a prime means of preserving his identity, keeping alive his memory, and trying to give sense and order to an external and internal world in crisis. Ramírez’s drawings are characterized by their monumental size, despite his chronic shortage of materials, and unusual, layered texture. But what has most attracted those who have been exposed to Ramírez’s drawings since the 1950s is his ability to construct a very personal visual language through a balance between tradition and modernity, and through a successful integration of the figurative and the abstract. The modern element and the abstract appearance of his work are achieved by a singular use of linear structures and concentric forms to represent distance and profundity in ways that do not follow the conventions of traditional perspective.

In admiring reviews by New York art critics, Ramírez was recognized “simply as one of the greatest master draftsmen of twentieth-century art.”

I saw Ramírez’s work for the first time at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Ohio State University’s contemporary art museum. In 1999 the center hosted the blockbuster traveling exhibition “Self-Taught Artists of the 20th Century: An American Anthology,” which had been organized by the American Folk Art Museum in New York City. The show included the thirty-one self-taught artists considered most representative, in the United States, of an emergent field called outsider art. Other than Ramírez’s works, which I had seen only in reproductions, I recognized pieces by Horace Pippin and Grandma Moses, and especially the paintings by Howard Finster, who created the 1985 cover for the Little Creatures album by the band Talking Heads. That exhibition introduced me to the works of Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, A. G. Rizzoli, Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, William Hawkins, Thornton Dial, and Purvis Young. The works of those artists were a revelation, but the exhibition was a contradictory visual and conceptual experience. The artworks in the 300-piece show, including fifteen representative ones by Ramírez, were not unified by any formal criteria, and the artists’ bodies of work had nothing in common with one another. The artists’ unique personal experiences were all marked by social marginalization, but they came from contrasting cultural backgrounds. The only common element, according to the curatorial statement, was the fact that the works were produced by socially marginalized self-taught artists who did not have any contact with the art world. This framing discourse, which valued the “outsiderness” and the social identity of the artists, had, from my perspective, a paradoxical result when used in a contemporary art museum dominated by discourses emphasizing formal qualities and conceptual frameworks. In the end, the two discourses, outsiderness and mainstream formalism, involved a strategy of cultural covering that simplified and romanticized the conditions under which the works were produced, ignoring the specific visual sources, personal experiences, and cultural worlds that shaped the artists’ intentions, thereby silencing their attempts to communicate.

Other than his name, the biographical information presented by the exhibition labels and in the short text on Ramírez included in the catalogue showed that the organizers knew only that he was born somewhere in the Mexican state of Jalisco sometime at the end of the nineteenth century, that he had been diagnosed as a chronic paranoid schizophrenic and secluded in an unspecified California mental institution during the Great Depression, and that he had been transferred, years later, to DeWitt State Hospital, where he produced hundreds of drawings and died in the early 1960s. The exhibition labels reduced his identity to his diagnosis as schizophrenic. The lack of information about Ramírez did not matter much to the museum, because the exhibition displayed his works and those of the other artists just as art, without an excess of context or biography. To be accepted by a contemporary art institution, an artwork produced by an outsider artist had to speak for itself. The exhibition catalogue claimed that his work, like that of the abstract expressionists, did not offer any clues about the life story of its producer. Ramírez’s works, however, showed not only clear references to his cultural roots, but also autobiographical references and visual representations affected by experiences of cultural displacement and seclusion.

Ramírez is a cross-border artist who produced all his work in a transnational third space, that is, far away from his homeland, completely marginalized from society in California.

The preliminary findings on his specific cultural world, his migration during a period marked by religious war in Mexico and economic crisis in the United States, his seclusion in two psychiatric hospitals, and the relation of all those experiences to the central motifs of his visual production played an important role in the organization of the 2007 exhibition of Ramírez’s art, which was held at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City and curated by Brooke Davis Anderson. The show broke attendance records and received considerable attention in the press and the media. In admiring reviews by New York art critics, Ramírez was recognized “simply as one of the greatest master draftsmen of twentieth-century art.”