How Will the Supreme Court’s ‘Swing Vote’ Judge Rule in Texas’ Abortion Case?

All eyes were on Justice Anthony Kennedy going into Wednesday’s U.S. Supreme Court hearing over the constitutionality of Texas’ omnibus anti-abortion law, House Bill 2.

And based on a few key points he raised during the 75-minute hearing, he knew it.

Kennedy is considered a critical voice in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, and before the sudden death of Justice Antonin Scalia last month, he was widely regarded as the “swing vote” between the court’s liberal and conservative judges. His previous rulings in abortion cases make him tough to read when it comes to how he’ll come down on the Texas law. Still, he is known to rule in favor of personal liberty. as he did in the 2015 same-sex marriage ruling. That’s a standard abortion rights advocates hope he’ll apply to abortion access.

Kennedy’s questions were “thoughtful,” said Jessica Pieklo, a constitutional lawyer and senior legal analyst at RH Reality Check. Instead of hammering attorneys representing Texas abortion providers, as his more conservative colleagues did, Kennedy asked specific, and at times revealing, questions about the heart of the case: how to balance the state’s interest in protecting patient safety without creating an undue burden on access to abortion.

“What we saw in those questions was Kennedy taking the allegations that the plaintiffs made [about the impact of HB 2] very seriously,” Pieklo said. “He’s looking for a solution.”

But the solution Kennedy appears to have in mind could prolong a case that many on both sides of the abortion debate have hoped to see resolved sooner rather than later. At stake: whether Texas can require abortion facilities to operate as hospital-like ambulatory surgical centers, and whether the state can require abortion-providing doctors to obtain admitting privileges at local hospitals.

Here, we’ll look at some of Kennedy’s stand-out moments from Wednesday’s oral arguments to find some hints at what could come next.

The “remand.”

Yesterday’s hearing started with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito hammering abortion provider attorney Stephanie Toti about whether the closure of more than half of Texas’ abortion clinics since 2013 really has anything to do with HB 2. Then, the justices wondered whether there is enough evidence that the nine ambulatory surgical centers that would remain open should HB 2 stand would have the capacity to treat all Texas patients.

That’s when Kennedy posed the key question:

“Would it be, A, proper, or B, helpful, for this court to remand for further findings on clinic capacity?” he asked.

Kennedy’s suggestion that the high court send the case back down is “not unreasonable,” said Jan Soifer, an Austin attorney and member of the legal team representing Whole Woman’s Health and other independent abortion providers. Especially, she said, after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, which has left the court with an even number of justices and a potential tied ruling.

“If he remanded it, that would really delay the ultimate questions until there’s a complete court seated, and it’s not unusual for the court to look for ways to rule that doesn’t involve a constitutional question.”

A remand is a way “for the court to kick the case down the road,” said Pieklo, without answering “the big question” as to whether laws like HB 2 can coexist with Roe v. Wade.

In fact, the Supreme Court recently remanded another high-profile case from Texas: Fisher v. the University of Texas, concerning affirmative action. After a round of oral arguments in 2013, seven justices ruled in 2014 to send the case back down to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. Now, Fisher’s made its way back to SCOTUS.

A 4-4 vote from the justices could send the case back down without any ruling on either HB 2’s admitting privileges or ambulatory surgical center requirements, Pieklo said. If a majority of justices vote to remand the case, they’d also have to make a decision to uphold, or strike down, one of these elements of the law.

Should they remand, justices would have to provide specific instructions on what the state and abortion providers must come back with, such as more evidence on clinic capacity, as Kennedy suggested Wednesday. The justices would also have to provide instructions on what happens with the law in the meantime, Pieklo said. Will the emergency stay granted by the Supreme Court in 2014 stand, and therefore, the status quo remain? That’s likely, Pieklo said, but nothing’s definite.

Kennedy: Is an increase in surgical abortions “medically wise?”

During the justices’ interrogation of Texas Solicitor General Scott Keller, Kennedy raised questions about HB 2’s effect on the number of medical abortions in Texas. They’ve increased nationwide, Kennedy noted, but decreased “significantly” in Texas.

According to best medical practices, patients can choose medication abortion within the first nine weeks of pregnancy, taking a two-pill regimen of misoprostol and mifepristone. HB 2 requires patients to take their pills, during up to four separate visits, in an ambulatory surgical center.

But in the post-HB 2 landscape, there are fewer open clinics and, as a result, longer wait times for appointments. That means patients generally are obtaining abortions later in pregnancy, past the point at which medication abortion is most effective, making surgical abortions their only option. While both medication abortion early in pregnancy and second-trimester surgical abortions are very safe, an earlier abortion is, statistically speaking, the safest option.

“I thought an underlying theme, or at least an underlying factual demonstration, is that the law has really increased the number of surgical procedures as opposed to [medication abortions], and that this may not be medically wise,” Kennedy said.

Pieklo called Kennedy’s point about medical abortions “fantastic,” showing he is taking seriously the plaintiffs’ argument that the law doesn’t have anything to do with patient health and safety.

“We see him really wrestling with this idea of if this is about patient safety, why is Texas driving [patients] into a riskier, more expensive procedure?” she said.

But the biggest indication that Kennedy may be seriously questioning the state’s “health and safety” claims? The fact that Texas’ medication abortion laws aren’t specifically challenged in the Hellerstedt case. Pieklo said that signals to her that Kennedy’s “taking the record and the law very seriously. I think that’s good either way.”

And finally, Casey.

As the Observer noted back in January, Kennedy is one of the primary architects of the “undue burden” standard, one of the key legal tests up before the court in Hellerstedt. In the 1992 Planned Parenthood v. Casey opinion, Kennedy and two other now-retired justices wrote that states may pass abortion restrictions, but only as long as they do not have the “purpose or effect” of placing an “undue burden” in the path of women seeking an abortion.

That vague definition of undue burden, which abortion rights advocates and legal experts see as a compromise that ultimately upheld Roe v. Wade but gave states more power to legislate abortion, is precisely what SCOTUS-watchers are hoping to get clarified. Plaintiffs in the case agree that states have a vested interest in protecting the health and safety of patients, as established in Roe v. Wade. But, they say, that interest must not outweigh the burden patients face in accessing a constitutionally protected procedure.

Will Kennedy will take a more credulous view of Texas abortion providers’ claims than his conservative colleagues? Does he believe that HB 2 has had a chilling effect on abortion access without providing a documented safety benefit to patients?

One exchange might provide a clue. Late in the hearing, Alito seemed convinced that states are within their constitutional right to “increase the standard of care up to the very highest anywhere in the country and it wouldn’t be a burden on the women. That would be a benefit to them.” Keller, the state’s attorney, agreed.

In response, Kennedy revisited his own compromise, established in Casey:

“But doesn’t that show that the undue burden test is weighed against what the state interest is?”

That’s the very question we’re all waiting to have answered. But, as Kennedy himself suggested, we might not get that any time soon.

Correction, March 3: Jan Soifer’s quote has been updated to include the word “ultimate” instead of “alternate.” The Observer regrets the error.

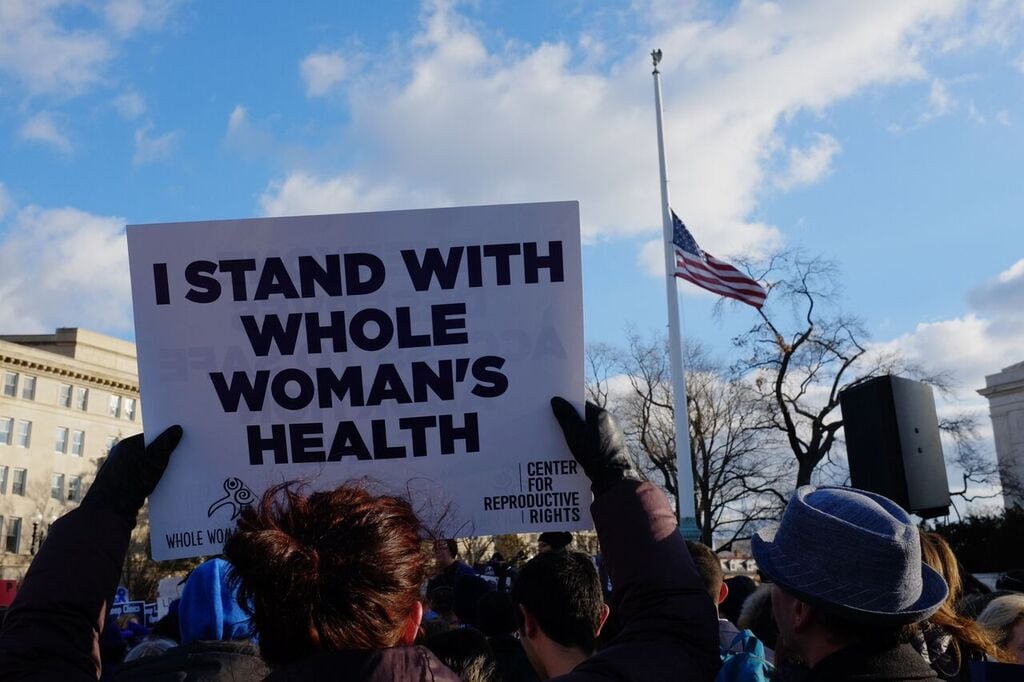

[Featured image: Alexa Garcia-Ditta]