The House Always Wins

Some legislators want to keep affordable housing out of their districts — and they've given themselves the power to do it.

A version of this story ran in the February 2016 issue.

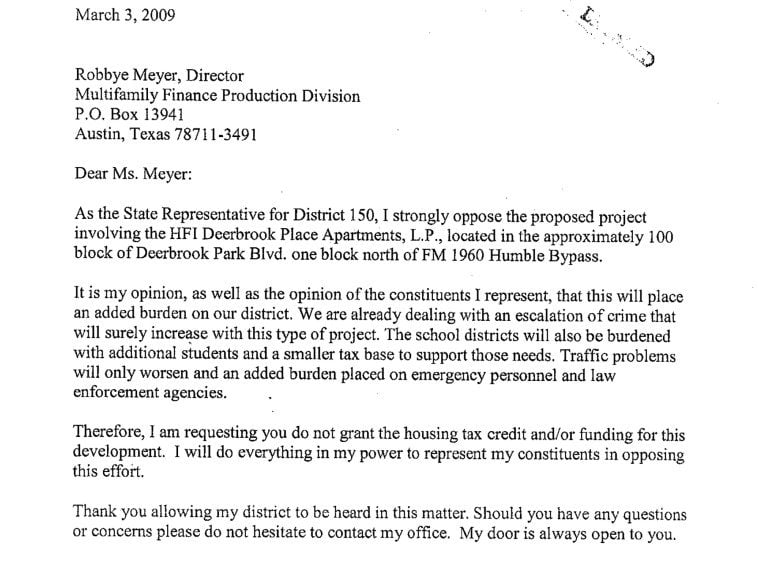

Above: Chandra Simmons with her daughter, her eldest son Shaquille Thomas, and her youngest son.

Some legislators want to keep affordable housing out of their districts — and they’ve given themselves the power to do it.

In Kay Smith’s opinion, middle-class people in the suburbs simply shouldn’t have to live near folks in low-income housing. “If you’ve worked and saved your money to be able to move to the suburbs,” she said, subsidized housing means that “people who are not willing to do that are now your next-door neighbors.”

A resident of the affluent Cypress area in northwest Harris County, Smith is a Republican candidate for the Texas Legislature and she’s honed her message to a fine point. Her campaign website announces: “The government wants to put Low Income Housing IN YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD which will diminish your property values immediately! Kay is leading the coalition to stop this from happening.”

Before running for office, Smith helped start the Cypress Coalition, a group of homeowners that has organized boisterous town hall meetings. She also helped a similar group get up and running in nearby Tomball. Her goal — and the mission of both groups — isn’t to stop a specific housing development but to halt any new low-income housing for families in House District 130.

On a damp November day, Smith takes me in her SUV around the district she hopes to represent. A slim, blond businesswoman with adult grandchildren, Smith tools through middle-class neighborhoods, down busy streets and past woods that still reflect some of the area’s recent rural character. She drives past a low-income apartment project, a gated development that she agrees looks nice from the outside and fits in with the neighborhood. But she also points out a two-story-high netting that she says was put up to prevent residents of another affordable-housing complex from throwing things that would damage cars and windshields in the adjacent medical facility parking lot.

“It’s just another example of how you have to accept the bad with the good with low-income housing,” she says. “The Fair Housing Act isn’t fair because it’s not fair to everybody.” If poor families are provided with a federally subsidized place to live in a nice neighborhood, Smith says, “Where’s the incentive for them to work hard and save?”

If Smith beats her Republican opponent in the primary — no Democrat is running — it won’t be hard for her to stop most low-income housing proposed for House District 130. Most likely, all she’ll have to do is send a letter to the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs (TDHCA) stating her opposition. She won’t have to give her reasons; a simple “no” is enough.

Thanks to a state law passed in 2001, Texas House members have the ability to stop affordable-housing projects, in most cases, simply by registering their objections. The legislative prerogative is an effective tool for affluent homeowners around the state who are increasingly agitated and vocal about keeping subsidized housing at bay.

Smith would be following in the footsteps of Allen Fletcher, the outgoing state rep for House District 130. In his first terms in office, he gave some support to such housing developments. But in the last couple of years, after dealing with crowds of angry constituents, he changed his stance. Last year he decided not to seek re-election.

The 2001 law, fair-housing activists say, empowers a handful of legislators and local government officials to exercise virtual veto power over most new low-income developments, making it increasingly difficult for poor people to find places to live. NIMBYism has rarely had such a powerful cudgel.

At the national level, public-housing policy has undergone a sea change in the last 30 years. The sprawling, substandard inner-city “projects” are largely a thing of the past. New low-income apartments and townhouses generally are outwardly indistinguishable from market-rate developments, and construction of them is dependent on a system of federal tax credits that go to their developers. Many low-income housing complexes are gated and most are well built, though often still located in high-crime or otherwise undesirable neighborhoods. Now, housing advocates and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) are trying to force states and housing authorities to place many of those new units in decent neighborhoods to help break the “cycle of poverty” often linked to segregation.

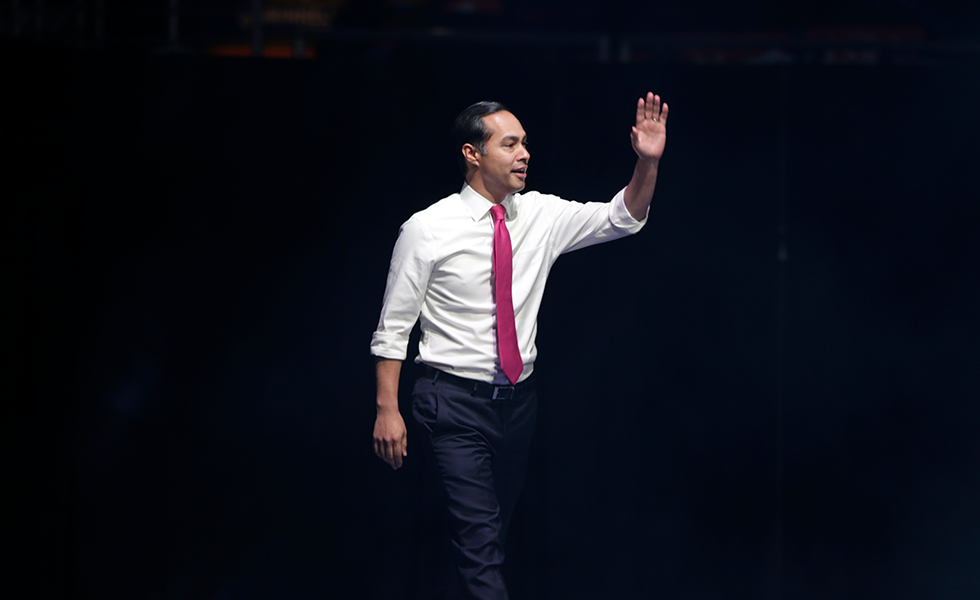

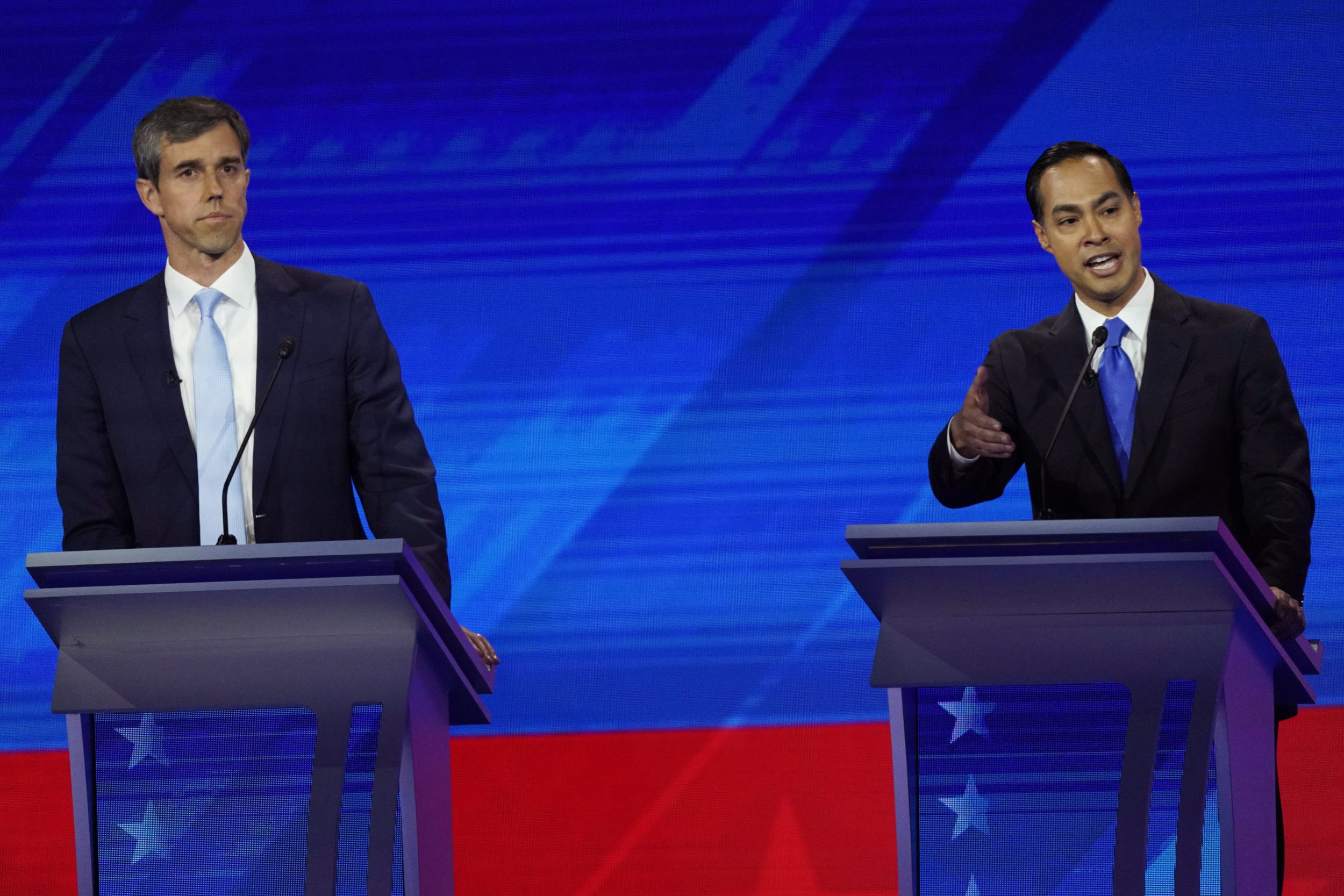

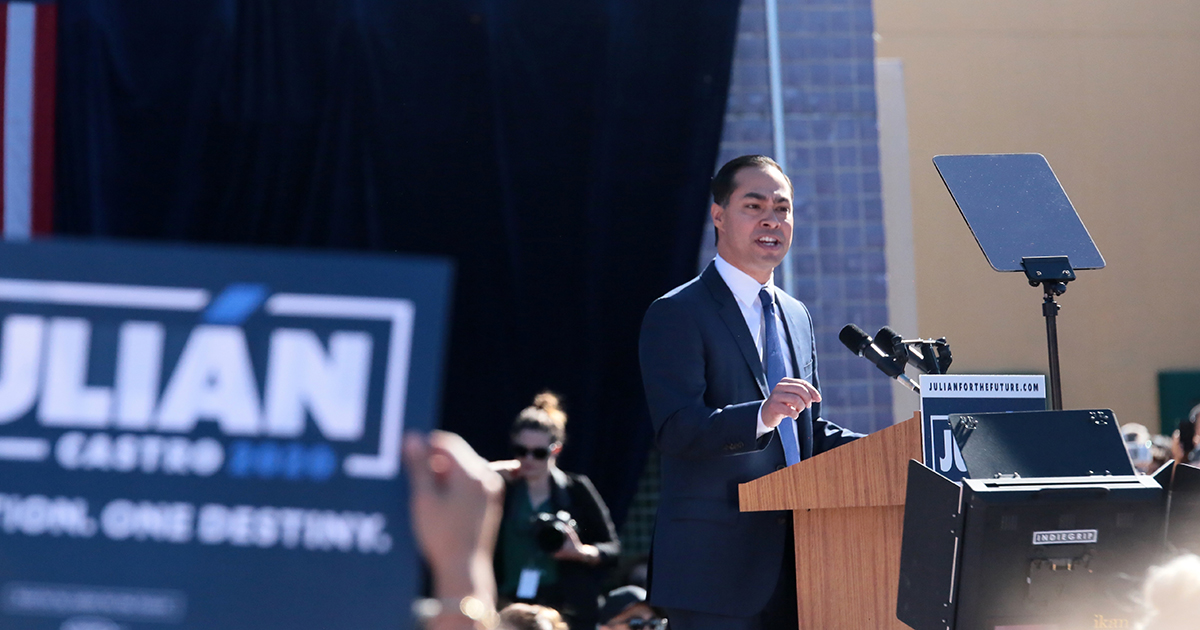

In July, HUD, led by former San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro, issued rules requiring that government entities receiving HUD money not only avoid racial discrimination but also actively reduce barriers to fair housing. If they don’t, they could lose millions of dollars in funding. Houston, for instance, will receive more than $41 million from HUD in 2016. Potentially the rules could require most new units to be built in economically vibrant areas — a longtime dream of anti-poverty and fair-housing activists.

But in Texas, HUD’s new approach runs smack into not only animosity toward public housing from some homeowners in affluent suburbia but also into the state’s idiosyncratic point system for selecting large housing projects backed by tax credits. Under the system, legislators hold so many points that in the vast majority of cases, they can make or break a housing project deal.

Texas legislators may face a tough choice: stay with their current system and continue on a collision course with the federal government or follow the new path laid out by HUD and federal court rulings. Local housing authorities also feel the strain. Increasingly, they’re being mandated, by HUD and TDHCA, to place subsidized apartments and townhouses in precisely the areas where individual legislators and local government officials are likely to veto them.

The point system “reinforces the NIMBY attitudes of people who oppose low-income families living in their communities because of prejudice and negative stereotypes,” said Betsy Julian, president of Dallas’ Inclusive Communities Project (ICP). Her group has been scoring major victories in court as part of a challenge to Texas’ allocation of tax-credit housing. In 2012, a federal judge ruled that the system reinforces racial segregation in the Dallas area. As a result, TDHCA voluntarily changed its practices not just in Dallas but statewide, to encourage housing development in safer, more prosperous neighborhoods. Then, in June, the U.S. Supreme Court, in a decision that was applauded by civil rights activists across the country, ruled that results, rather than intent, can be used to prove racial discrimination in housing.

Julian said the point system is “making ICP’s efforts to help families find affordable housing in decent, safe areas much more difficult.” It also may put TDHCA in more legal trouble.

In 2001, Texas legislators gave themselves a trump card over subsidized housing projects. Under the law, each representative and senator would have “points” to add or subtract from the scoring system TDHCA uses to select developments relying on federal tax credits. The Legislature also gave local governments and certain community groups the authority to add but not subtract points. The Texas Senate gave up its power to award points in 2013. Since the community groups have fewer points to award, they can seldom tip the scales on a project. But in case after case, legislators’ actions — in giving, withholding or subtracting points — have ended up as the deciding factor in whether projects get funded.

When those points are awarded or subtracted, the ranking of development applications is often turned on its head, completely changing which ones will get funding and get built, according to both John Henneberger, co-director of the Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, and ICP attorney Mike Daniel.

In Dallas this year, for instance, according to information compiled by Henneberger’s and Daniel’s organizations, before the legislator and local government points were applied, eight projects were in line to get funding — one for elderly people and seven for families. After those points were accounted for, five elderly-only developments got the nod while only three for families were approved, even though poverty figures for the Dallas area suggest that far more families than senior citizens need subsidized housing. And two of the three family developments that did get approved are in census tracts where poverty rates are more than 35 percent. The ones that lost out were in much more affluent areas.

Since the 2001 legislation, few major housing projects funded by tax credits have moved ahead without legislator approval. For instance, in the area of northwest Harris County encompassing four legislative districts, only three such family developments have been approved and only two have been built, with a total of fewer than 200 units. The third faced so much opposition that in 2015 its developers gave up and changed it into a project for senior citizens.

Last year, state Representative Tony Dale, a Cedar Park Republican, filed a two-line letter objecting to a project that the Austin City Council had already approved for city funds. Dale told reporters he objected at the request of Don Zimmerman, the single Austin City Council member who opposed the project. (A TDHCA staffer, though, said other problems with the project might have kept it from being funded even without Dale’s letter.)

“You’d think we were building a nuclear reactor. It’s like everybody gets a vote except the poor people who might get to live there.”

(Fletcher and Riddle did not respond to numerous requests for comment.)

Riddle, elected in 2002 to represent a northwest Harris County district, has registered her objections to low-income housing proposals, including some for senior citizens, year after year. For developments planned for families, the letters routinely complain that crime rates “will surely increase with this type of project,” property values will decline and schools will be overburdened.

In a January election mailer to constituents, Riddle warns that “by pushing low-income apartment housing into our neighborhood, Obama and ‘community improvement’ developers believe in the redistribution of poverty among American neighborhoods in the name of diversity.”

Like other legislators, Riddle says her district doesn’t need more subsidized housing — that it was “inundated” with it. That’s not what the data suggests, though.

According to an analysis done by the Texas Low Income Housing Information Service, no competitive tax-credit developments for families have been built in her district since 2000. The picture is similar in other House districts in that part of Harris County. Meanwhile, more than 500 low-income units in four developments have been approved in one zip code in a poor part of Houston’s north side.

A Houston Chronicle analysis, based on state information through 2013, showed the same pattern: Tax-credit developments “cluster[ed] in the same areas decade after decade,” the Chronicle found, while other neighborhoods, including most west of downtown between I-10 and U.S. 59, were almost empty of them.

Affordable-housing advocates say the point system is helping to build a “wall of segregation” shielding upscale suburbs, particularly in Houston and Dallas.

Racial segregation in Dallas’ low-income housing “is caused by operation of the municipal and state representative … points,” Daniel told TDHCA Executive Director Tim Irvine in a letter in June. Daniel said the agency has broad discretion to figure out how to weigh legislators’ and local officials’ objections to housing projects — discretion it needs to use to comply with its federal obligations to avoid racial segregation.

TDHCA officials declined to comment in any detail on that assertion. “Like all executive agencies, TDHCA may serve as a resource to the Legislature, but we are tasked with administering and following state law,” agency spokesman Gordon Anderson said in an email.

Chandra Simmons is one of the people caught amid the conflicting pressures of the state and federal governments and grassroots resistance to affordable housing. When Simmons was young, she seldom called anywhere home for long. She was born in Houston, but her dad’s career in the Navy took Simmons and her siblings to South Carolina, California and Washington state. In 2011, while living in Kent, Washington, and working with special-needs and at-risk students in after-school enrichment programs, she developed serious health problems. She’d been diagnosed with sarcoidosis years before, but the auto-immune disease had gotten progressively worse. Stress and environmental factors such as smoke, chemicals, mold and pollution cause it to flare up, bringing on symptoms similar to rheumatoid arthritis or lupus and sending her to the emergency room with swelling that, untreated, can start shutting down her organs.

When she could no longer handle the physical demands of her job, Simmons returned to the Houston area. She moved in with her parents in Cypress for a while, but her sister and niece were also living there, and the addition of Simmons and her three kids — two sons, then 17 and 9, and a daughter who was 6 — strained the house to the bursting point. Too ill to work regularly, she qualified for a Section 8 rent voucher and started looking in suburban communities including Cypress, Missouri City and Sugar Land. But rentals in good neighborhoods at prices that her $1,350 voucher would cover are few and far between.

Now 43, she’s spent the last four years moving around more than ever — to four different run-down houses. “I’ve heard it said that [with a voucher] you can only afford to go to the ghetto,” she said. She said she was never offered tax-credit housing as an option but that she’d have been willing to consider it.

Since the 2001 legislation, few major housing projects funded by tax credits have moved ahead without legislator approval.

Simmons moved out, but her new place, in an historic African-American area called Acres Homes — one of the most crime-ridden in the city — was no better. The home had been broken into, and rats and snakes had invaded. The air conditioning didn’t work and water flooded the downstairs.

The family’s next stop was a place in Missouri City, where neither the air conditioning nor the furnace worked. When she complained, she said, she was kicked out of the voucher program, and only got back in when a nonprofit group helped her find an attorney to plead her case.

The last Section 8 house she lived in, in the western suburb of Katy, had both electrical problems and water leaks. Breakers would trip, light switches didn’t always work, and the wiring on her washer and dryer got fried. She was eventually told that the house wasn’t properly grounded. It was so bad, she said, that having the hair dryer on in one room and the microwave on in another would blow a fuse.

In October, she moved back in with her parents, sister and niece, who now live in Sugar Land on Houston’s southwest side, and started the housing search all over again.

She was taking paralegal classes and hoped to find something near her school and her parents’ house. In November, Simmons finally found a house in Sugar Land, she said. The landlord was willing to take less rent than what he was asking, she said, but housing authority officials asked him to go even lower. Almost two months later, the two sides are still arguing and she and her kids are stuck at her parents’ house. Her oldest son was planning to move away to go to college, she said, but has stayed to help her instead.

“I haven’t been able to find housing in good condition in a good area in the voucher [price] range,” she said. She’s come to believe that the Houston Housing Authority’s system is geared toward keeping poor people in dumps.

Tory Gunsolley, the head of the Houston Housing Authority, says the problems that Simmons ran into go way beyond the scope of his agency.

“Houston historically has been a very affordable city, but it’s becoming less and less so, particularly for people who make working-class salaries and below,” he said. “There’s a growing sense in Houston that we need more affordable housing.” He pointed to a recent front-page Houston Chronicle story tracking another local woman through an equally desperate search to find a home before her voucher expired. She succeeded only when a relative agreed to rent a property to her for a short time — a temporary solution.

One factor, Gunsolley said, is TDHCA’s new rules about where tax-credit housing can be built. The rules give points to developers for building in “high-opportunity” areas — the same communities where opposition is often the most intense. Meanwhile, “huge parts of Houston,” areas where low-income housing might not meet opposition, are now effectively off-limits to new tax-credit housing, he said.

In order to get approval to build new housing in a poor area, the developer must show that it’s part of a community revitalization plan, a detailed program to revitalize an area with services, transportation and private investment. “That’s a high bar to overcome,” Gunsolley said. As a result, he said, affordable housing is being pushed “farther and farther outside the city core” — to places such as Cypress, where Kay Smith and Debbie Riddle and resident groups are able to trip up developers.

Meanwhile, with rapid gentrification in some parts of the urban core, poor residents find themselves hemmed in. The result is a new concentration of poverty in the older, first-ring suburbs — a national trend. Poor people “are stuck,” said Tarsha Jackson, Harris County director of the grassroots Texas Organizing Project. “They can’t come into the city and they can’t afford to go farther out.” In some of those older suburban areas around Houston, she said, such as the one near her home in the Greenspoint area on Houston’s northern edge, “It’s like a war zone.” People “are squeezed between higher-priced regentrification downtown and white outer suburbs.”

Gunsolley, as Well as Henneberger and Julian, see HUD’s new push to desegregate low-income housing as a major policy shift. For one thing, it allows other entities, such as Texas Organizing Project, to file complaints with HUD alleging that public agencies getting HUD money aren’t doing enough to fight segregation. It’s a much different approach, Henneberger said, than simply fighting year after year for a share of the shrinking federal funding for housing.

“As much as I’m a cynic, there are changes in attitude going on,” Henneberger said. Discussions about equality and integration are at least possible now.

In the fall, House Speaker Joe Straus and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick instructed legislative committees to study Texas’ housing programs and consider if changes are needed to comply with the Supreme Court decision and HUD’s new rules. “There is much more recognition now of segregation’s legacy as a problem that needs to be eradicated,” Henneberger said.

In Houston alone, “there is more going on, on more fronts, over fair housing and questions of equality and race than anyplace outside Baltimore,” he said.

But legislators such as Riddle are ready to do battle to protect the system.

“Our voice is heard through the points,” she says in a video on her website. “I am never going to allow my voice or your voice to be extinguished.”

The rules give points to developers for building in “high-opportunity” areas — the same communities where opposition is often the most intense.

“We’ve got more than enough [low-income housing]. Why would it even be considered when you know you will get a fight?” Riddle asked.

Johnson said recently that he hadn’t heard of the incident, but he doesn’t think elected officials, “who have to go to the voters for their jobs,” should be able to nix affordable-housing projects. In the six years he’s been in the Legislature, he’s sent letters supporting housing projects a handful of times. If he didn’t, the housing might not get built. “Your inaction becomes a statement,” he said.

Kay Smith says citizens should have more, not less, input about locating low-income housing in their neighborhoods, and in that view, she reflects at least some of the people she’d like to represent.

“If we had all these housing projects I would be afraid to go out in the evening,” wrote one Cypress woman to TDHCA in February 2013 in opposition to a proposed housing development for families in the town of Spring. “And with no public transportation, who knows who would be walking the streets?”

In an email on the same project, a businessman said he would move away if the project went forward. “It will certainly cripple the housing market … resulting in a mass exodus of the tax base,” he wrote. “Once we’ve gone further north to escape the crime and filth, good luck with supporting the [school system] and infrastructure.”

Smith said she knows of people in Cypress and Tomball who are moving even farther out from Houston in order to avoid having a low-income development near them. She worries about crime and the effects on schools, and the possibility that having more poor people in the area might bring city buses onto the suburban streets.

“You’d think we were building a nuclear reactor” rather than low-income housing, Henneberger said. “It’s like everybody gets a vote except the poor people who might get to live there.

[Featured image: Chandra Simmons with her daughter, her eldest son Shaquille Thomas, and her youngest son. Photo by Todd Spoth.]

To support journalism like this, donate to the Texas Observer.