Why a Small Offense Shouldn’t Have Life-Altering Consequence

Opinion: Nearly 10 years ago, I was arrested and detained in jail for 45 days after failing to appear in court for a low-level, non-violent offense. Today, I’m fighting so that others don’t have to go through what I did.

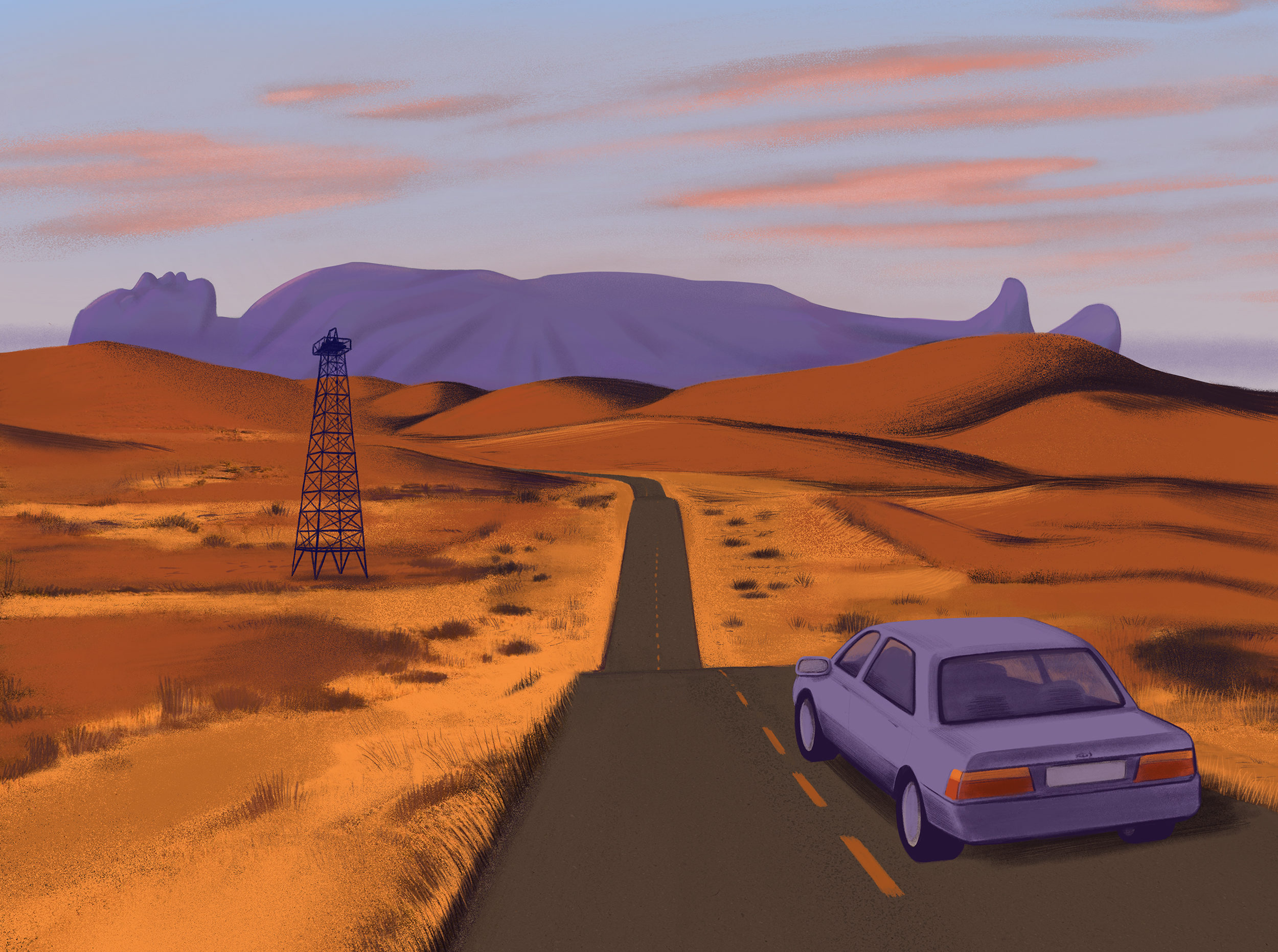

Above: I needed to not just put my pain on display. I needed to do something about it.

Standing in San Marcos’ crowded city hall lobby this past September, I watched the faces of the city’s leaders. Dozens of residents—business owners, college students, city staff, families of police officers—had come to speak for or against a proposed cite-and-release ordinance. Months later, we are still waiting to hear a decision from the city council. The ordinance, if it is approved, will allow police officers to write citations for low-level, nonviolent Class A and B misdemeanors versus arresting people and taking them into custody. At that September meeting, the council members’ expressions ranged from mildly annoyed to focused and attentive. Some occasionally glanced up from their piles of papers to look a speaker in the eye. Others kept checking the clock.

As I watched the council, I imagined what it must be like for them, sitting between the people and the police, trying to decide whose concerns were more pressing.

I had always assumed the people’s needs and concerns came first—and not the people with the badges and the guns—but I’ve learned that this is often not the case. It’s upsetting. Then I remind myself that the city council members are just people too. People with fancy titles and more inherent powers, protections, and influence than 90 percent of the local population—but people, nonetheless. People who can be subject to their own underlying faults and misgivings. People who could have made some of the same banal mistakes that this city’s police department aggressively arrests for every day, like driving without a license or carrying less than four ounces of marijuana. I remind myself that these people have their own families, personal difficulties, and bills to pay.

And I hope—with everything I have left in me—that they will see me as a person too when it’s my turn to speak. Please. I am a person too.

*

The fear of not being seen as a whole person became ingrained in me in 2010, when I was still a student at Texas State University. That’s when I was held for 45 days in pretrial detention in the Hays County Jail. I had been arrested on a warrant issued after a $25 check I wrote for groceries bounced. During my month and a half in jail, I was never visited by a court-appointed attorney. I lost my car, my apartment, and my storage unit. I wrote about the experience for this publication in February 2019. When I told this story, some people were in disbelief; others were in outright denial. How could anyone spend that much time in jail without seeing a court-appointed attorney for something as little as a bounced $25 check? I wondered that too.

I spent much of those first few weeks worrying if I had done the right thing in writing the essay. My dad, a retired, disabled vet, concerned about my safety, urged me to take precautions. But people began to see me differently.

People I had only known professionally through art events or poetry sent me private messages to show their support. My essay was widely shared and read. It’s even the basis for an Independent Lens documentary embedded with this article.

I had shown the world my most vulnerable moment—but I needed to do something more. I needed to not just put my pain on display. I needed to do something about it.

*

Getting ready for work a year ago meant pulling a clean white button-up out from the dryer, lacing up my black slip-proof shoes, and grabbing my apron before rushing off to the San Marcos IHOP just down the street from my tiny apartment.

Today, getting ready for work requires a couple of hours of rereading emails for updates to local policy initiatives, checking in with a few people who’ve spent anywhere from a couple of nights to a year in the Hays County Jail, and speaking in front of city council, lawyers, judges, and county commissioners about the irreversible effects of detention on their most vulnerable residents. I represent them throughout the state as a community organizer and activist—and it’s the scariest thing I’ve ever done.

I began working with Mano Amiga, a social justice advocacy organization, in April. The organization has collaborated with local advocates and community organizers to determine the scope of the problem with pretrial detention in all of its forms and local policy. Earlier this year, at the request of county commissioner Debbie Ingalsbe, Mano Amiga received a report about how often Hays County officers used the cite-and-release program in 2018. The report notably included the race and ethnicity of those who had been arrested, and who had been released after a citation. Mano Amiga found that in San Marcos, the county seat, 50 percent of the people arrested for cite-and-release eligible offenses were under age 25. Out of the 72 black people with cite-and-release eligible offenses, not a single one had been offered a citation; all had instead been arrested.

In this college town, that meant that half of the people being arrested were just like me: college students who had moved to the city to get an education, but wound up having their lives disrupted for minor offenses.

After having been in the custody of the local police myself, I know that if the San Marcos Police Department uses their unguided discretion—which will be based on my previous record, my attitude, and any other views they hold about queer black femmes—I could easily end up back in a holding cell for something as simple as jaywalking. I know that I could easily spend a couple of weeks sitting in jail because I cannot afford my own attorney or bail.

Through all of this, there is a disconnect between the policy and the people. And I know that officers who are carrying out this policy are people too. Most of the time, I believe they are trying to get it right, but occasionally, they make a mistake. And their mistakes can cost our community more than we should ever be willing to lose. I humbly recognize that I don’t have all the answers. No one does. But this is why I choose to put myself and my story out there—so at least my experience can help us work toward a solution.

*

Before the city council meeting, I called my dad. He told me that he was proud of me and of the work I was doing. A lot of people are too afraid to speak up for themselves when facing their local government, he told me. I couldn’t help but cry. I didn’t tell him then, but I didn’t want to go in front of the city council again and try to convince them to help people like me. I didn’t want to have to keep saying, “People make mistakes, but that doesn’t mean you devalue them. Everyone deserves some dignity and respect. Everyone deserves a chance to get their life right.” I didn’t want to be the spokesperson for change in my city. But that’s who I am now.

I can hold my city council accountable and ask them to prioritize the residents who are at risk of having their lives disrupted by being arrested for low-level, nonviolent offenses. I can ask them to pass an expansion to the cite-and-release ordinance, one that covers all the eligible offenses as voted on by the state of Texas and including transparency on the part of the San Marcos Police Department when it comes to the age, race, and ethnicity of the people who are arrested.

I can provide a space of healing for the people who have spent time in jail or prison or any other form of detention. I can explain the policy to them. I can provide them with information about the basic resources that they may need, including physical and mental health facilities, food banks, rehabilitation programs, housing support, and employment assistance. I can be someone they can come talk to or sit with. I can make sure their stories are heard. I can make sure they are seen.

This article has been updated.

Read more from the Observer:

-

A World Without Immigrant Prisons: Law professor and author César Cuauhtémoc García Hernández wants you to believe it’s possible.

-

As Port Neches Plant Smolders, Trump Rolls Back Safety Rules for Chemical Plants: After a deadly explosion in the town of West in 2013, Obama implemented stricter safety rules for chemical plants. Trump’s EPA has just undone them.

-

Texas’ Method for Funding Courts is a Colossal Waste of Time and Money: Criminal fines and fees, in addition to trapping poor people in a cycle of debt and incarceration, are an incredibly costly source of revenue for local governments, according to a new report.