What’s Left?

For nearly four decades, white liberals have dominated Austin politics. Now the city may finally embrace true progressivism.

A version of this story ran in the December 2013 issue.

Above: Austin City Council meeting, November 21, 2013.

What you think you know about Austin is true: It is the most reliably liberal city in a conservative state. It is a transformed sleepy college town that has grown along with the rest of Texas into an economic draw. It is the sort of progressive place where politicians vote to require construction companies that receive city incentives to pay their workers a livable wage. It is largely still the same place where so-called progressive environmentalists can go toe to toe with developers.

It is all of that. But it is also the home to what is, at best, an odd remnant of Jim Crow: a deal—locally known as the “gentlemen’s agreement”—that reserves two of Austin’s City Council seats for members of the city’s African-American and Hispanic populations. The deal dates to the 1970s as a way to prevent the city’s Anglo business community from defeating minority candidates. But what began as an effort to diversify the City Council became a cap on African-American and Latino representation.

While most American cities have used single-member districts—in which a council member is elected by a specific area—to diversify their politics, Austin had, until very recently, held out. It was for many years the largest city in the country without single-member districts, and an anomaly even in Texas, where formerly all-white suburbs like Arlington and Irving have opened their local politics to more minority representation. In Austin, all seven councilmembers were elected citywide, an expensive proposition that in practice has meant that the white liberal establishment usually picks the winners.

In practical terms, that looks like this: The 2011 City Council elections saw the return of retired engineer and public-health expert Laura Morrison, a white woman. Chris Riley—a lawyer and avid bicyclist who lives in a restored house that dates to 1890—was re-elected. Riley had inherited his seat in 2009 from white retired airline pilot and U.S. Navy veteran Lee Leffingwell, who decided to run for mayor. Another 2011 race ended in a runoff between two white women in which challenger Kathy Tovo upset Councilmember Randi Shade.

A year later, in 2012, the status quo held again. Leffingwell was narrowly re-elected as mayor over a white woman, former Councilmember Brigid Shea, and a young white man, Clay DeFoe. White female challenger Laura Pressley took on the gentlemen’s agreement by running against Mike Martinez, who holds the designated Latino seat. Pressley lost by 9 percent. Incumbent Bill Spelman, a white University of Texas professor, fended off six challengers, including young Hispanic Republican Dom Chavez. The Council’s lone African-American, Sheryl Cole, won too, beating white male challenger Shaun Ireland by 50 percentage points, thereby holding on to the seat reserved for African-Americans.

The resulting City Council—elected by just 10 percent of eligible voters—of five Anglos, one African-American and one Latino doesn’t reflect Austin’s increasingly diverse populace. Anglos make up only 49 percent of Austin residents, according to the 2010 Census, making it a so-called majority-minority city. Though the African-American population has been declining in Austin, Hispanic residents are moving to the city in relative droves, yet they were limited to one City Council seat. Still, the deal persisted for four decades in spite of its distinctly anachronistic conservatism, which is an uncomfortable fit for a city that claims to keep it weird.

Finally, in 2012, Austin voters threw out the gentlemen’s agreement, approving a plan that will seat 10 council members, all elected from single districts, and an at-large mayor.

Austin is now on the brink of its first major electoral change in decades. What’s coming will replace an awkward (at best) system that reeks of establishment politicking, or (at worst) has entrenched the power of Austin’s white liberal oligarchy. But the change is not universally loved. Some members of the Austin political establishment are leery of it. And the two political consultants who were once allies and have helped define Austin politics for a generation find themselves on opposite sides of the issue. Peck Young has stumped for ending the gentlemen’s agreement. He hopes that the new system will open Austin politics to council members from all corners of the city. Young and other single-member district proponents contend it will be easier and cheaper for candidates to campaign in a defined area than citywide. In fact, with new maps now in place, candidates from parts of Austin that once had little chance of gaining representation are already expressing interest in running for office.

Still, David Butts—who some have called Austin’s liberal version of Karl Rove—worries, like many of the city’s old guard, that the new system will throw open the doors of City Council to not just more Latino candidates, but to a group so resoundingly reviled in Austin politics that it has been largely shut out of power: Republicans.

The Texas of David Butts’ youth was informed by Lyndon Johnson but headed for John Connally—a place where racism was real and established, driven by the Ku Klux Klan and by white citizens’ councils. It was a nasty time.

Even as a kid, Butts says, he “knew what he felt,” and in 1960 he liked John F. Kennedy. In Meridian, a small municipality about halfway between Waco and Dallas, that meant street fights with kids who didn’t think much of the senator from Massachusetts. “I had to whip my weight in kids who thought that Kennedy was going to bring the pope into the White House if he got elected,” Butts says. “It was bad. It wasn’t like we were trying to kill each other, but we weren’t playing, you know?” He was 10.

Butts’ precocious interest in politics was furthered by the demographic data he says he started pulling from precinct boxes in 1962, when he was 12. It was from this data that he started to figure out the sort of math that would eventually make him a must-have consultant for Austin’s politicians. “What I started to realize [was] these precincts are like fingerprints; they tell you something about the type of people that live [there]. There are patterns here to be seen,” he says. “And so I began my great love affair—and I still have it today—of looking at political numbers and trying to discern from that what it means.”

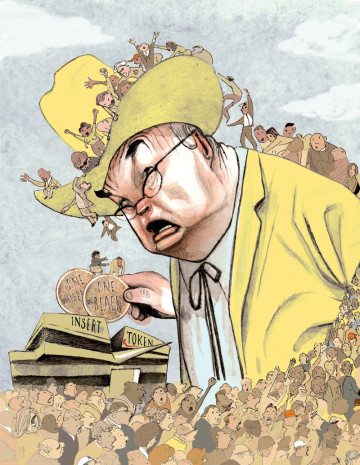

Butts transferred to the University of Texas for his junior year in 1970, where he found like political minds on the left. There he met William “Peck” Young, an Austin native who would crust over into a tough, colorful, big-gutted, hat-and-buckle-wearing consultant and who, along with Butts, would have a huge influence on Austin politics.

While Young has consulted for city and statewide politicians, Butts has remained exclusively local. He has a hand in nearly every council election and seat. As a kingmaker in Austin, Butts employs the same confrontational instincts that made him a street brawler on behalf of Jack Kennedy in 1960. “David is a political operator,” Young says, “that over the last 20, 25 years has elected all of those [Austin City] Councils.” That all councilmembers answer—through channels of election funding and power brokering—to Butts is an oft-repeated local legend. Butts laughs this off and says just because he helps council members get elected doesn’t mean he has control of City Council. Whatever the case, there’s no doubt that, as Young puts it, “David is the establishment.”

And this being Austin, it’s a liberal establishment. Both Butts and Young identify with progressive politics. In that respect, the gentlemen’s agreement that they helped arrange was a true oddity: It tried to defeat institutional racism by institutionalizing race. That neither Butts nor Young found the arrangement all that palatable—a “best-we’re-going-to-get” sort of deal—makes the fact that it stuck around well into the 21st century disturbing. Progressive the gentlemen’s agreement is not.

But oddly enough it was the gentlemen’s agreement that aided Austin’s emergence as a bastion of white liberalism.

Like so many other small southern towns, mid-20th century Austin was dominated by white politics. It was, after all, still a small place. In 1965 there were just 214,000 Austinites. By contrast, Dallas already had well over 600,000 people within its limits by 1960; Houston was already close to boasting one million.

The modern Austin political establishment emerged in the early 1970s, depending on whom one asks. Butts’ version of the story starts with Wilhelmina Delco. Delco would eventually ascend to become Texas House Speaker Pro Tem, but in 1968, she ran for a seat on the Austin school board. Butts says then-future Austin Mayor Roy Butler and “Will Davis, who was a [John] Connally crony,” served together on the school board at the time and backed Delco. “Bussing was getting ready to happen, and they thought that a black person should be on the school board, and they got behind her,” Butts says. “She had serious conservative opposition, and she did not win by any massive landslide, but she did win.”

Then, in 1971, Berl Handcox mulled a run for City Council. Handcox grew up in Denton, was a veteran of the U.S. Navy and served as the Equal Employment Opportunity Coordinator for IBM. According to an oral history account posted on the University of Texas’ web site, Handcox “and his family challenged the unwritten rule that forced African Americans to live almost exclusively in East Austin. He became known within the black community as president of a group called the Young Men’s Progressive Club, and this exposure inspired some of his associates to suggest that he run for a seat on the Austin City Council.”

That he did. When Handcox won, he became the first African-American elected to the Austin City Council since reconstruction. Butts says that a coalition of progressive students backed Handcox, even though he and his colleagues weren’t exactly sure what they were getting into. He describes it this way: “We didn’t know him at all—he might have been a Republican for all we knew, he might have been anything. The people running against him were conservatives, business-oriented. We thought it would be a good thing to elect a black person to the Council.”

In 1975, John Treviño became the first Hispanic member of the Austin City Council in much the same way—with separately organized support from the business community and the progressives. “The liberal-progressive community, at best, was sort of brought in as an afterthought,” Butts says. “Our attitude was, ‘Sure, we want to see minorities elected.’”

But in 1977, Treviño faced a difficult re-election campaign. Butts puts it bluntly:“A bunch of the old racist businessmen want[ed] to run somebody against him, beat his ass, and get the Mexican out of office.”

With Treviño facing strong opposition from the business community, Young says, Ed Wendler, an Austin attorney who carries his own level of legendary status, went to Bill Youngblood with a threat. At the time, Young and his people were preparing a legal challenge to Austin’s at-large voting system via the Voting Rights Act of 1965. They would claim, as activists in many cities would, that at-large elections disenfranchise minority voters.

Youngblood, another honcho in midcentury Austin politics and a friend of Roy Butler’s, was close to the business community. Young says Youngblood and Butler weren’t racists, but they had put money behind Treviño’s opponent. So Wendler offered Youngblood “a way to fix” the pending legal issues: “You pull all the money out from behind Treviño’s opponent, and you guarantee there is one Mexican and one black on the City Council for perpetuity, and Young and his people [won’t] ever get fucking single-member districts.”

It was a way for both sides to call a truce and get some of what they wanted. The business leaders got the continuation of expensive citywide at-large elections, which helped them maintain control of city politics by steering money to the establishment’s choices. Meanwhile, Austin’s emerging progressive kingmakers, including Butts and Young, could guarantee at least two minority council members. The result was that the business community agreed to support the election of one African-American and one Latino council candidate—regardless of the city’s demographics. Thanks to citywide at-large elections that setup has persisted. It became known as the gentlemen’s agreement.

Attorney David Van Os, who has filed legal challenges to the gentlemen’s agreement, has a more cynical take on why the gentlemen’s agreement came about. “The specific motivation was to let the ‘Blacks and Mexicans’ have one seat each in order for the city to be able to defend against the voting rights lawsuits that everybody knew were coming, and thus preserve the at-large system. It was not for the purpose of ceding representation to the communities of color, it was for the purpose of maintaining the at-large system,” Van Os wrote in a 2008 email published in the Austin Chronicle. “That was what the business interests wanted because they believed maintaining the requirement for candidates to campaign city-wide would maintain the need for business money to run campaigns and thus keep promoting the elections of candidates friendly to the business interests.”

Van Os also details how the arrangement morphed into status quo. “[It is] where the alliances between conservative white business interests and certain elements of the communities of color started to bloom,” he notes. “The white Anglo grassroots voters did not contribute campaign dollars to the Hispanic and African-American candidates like they did to the Anglo candidates. So Hispanic and African-American candidates learned to look to the business interests to finance their campaigns, and the business interests were pleased at the opportunities to purchase City Council candidates who turned into compliant City Councilmembers.”

With the gentlemen’s agreement in place, elections in Austin became eminently predictable, and voter turnout cratered.

In 1971, not long before the gentlemen’s agreement was forged, 56.8 percent of registered Austin voters showed up at the polls, according to a 2009 study by Austin Community College’s Center for Public Policy and Political Studies, which Peck Young runs. Turnout then began a steep decline. By 2009, just 13 percent of voters turned out. In 2011, a mere 7.4 percent of eligible Austinites bothered to vote in city elections.

The people who did turn out were mostly white. As part of his report, Young observed that the Austin precincts with the highest voter turnout were “characterized by an Anglo population that exceeds 90 percent, an African American population that is less than 1 percent, and an Hispanic population that is less than 7 percent.”

In 2009, the city’s most active voting population, Young’s report concluded, was “located in northwest Austin”—a region that generally features a concentration of wealth.

Councilmembers elected in 2009 generally

reflected that voting population. Then-Councilmember Leffingwell, the white retired airline pilot, earned more than 50 percent of the mayoral vote. Chris Riley beat Perla Cavazos, a young Hispanic woman who challenged the gentlemen’s agreement by running for a seat not reserved for a Latino candidate. She would have been the council’s second Latino member. But she lost, earning less than 35 percent of the vote. Two years later, the Chronicle’s Wells Dunbar suggested that Cavazos’ loss lent “perspective to the failings of the at-large system.” Dunbar noted that “Cavazos said political consultants advised her that she needed at least $200,000 for a competitive citywide run, and added that the at-large system ‘perpetuates a cycle of forgotten neighborhoods and people, where voter turnout is low and easy to ignore.’”

Meanwhile, the 2009 election continued to perpetuate the gentlemen’s agreement. Former Austin Firefighters Association head Mike Martinez was re-elected to the Hispanic seat with 84 percent of the vote, and Sheryl Cole was returned to the African-American spot with roughly 83 percent.

Though challengers like Cavazos sneak through, and assigned seats have been swapped, the arrangement has seen surprisingly little in the way of a real fight. Young says this is not for lack of legal efforts. In fact there have been legal challenges to Austin’s at-large system over the years, and several referendums to install single-member districts have failed.

“Many white progressive voters were fooled by the illusion of equal access to the political process created by the two minority-held Council seats—just as the business moguls who manipulated the ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ into being foresaw,” Van Os wrote in a message posted to the site of the Austin Neighborhoods Council. Of the court challenges, which he helped lead along with the NAACP and MALDEF, Van Os wrote, “[T]he courts held that since one Hispanic and one African-American were consistently getting elected to the Council, thus occupying [two] out of [seven] or 28% of the Council, the communities of color therefore had equal access to the political process so there was no Voting Rights Act violation.

“[We] argued vigorously that channeling minority political access into two designated Council seats in elections whose outcomes were controlled by the majority white community rather than by the minority communities themselves was NOT equal access to the political process.”

It was a losing legal argument. The genius of the gentlemen’s agreement was that it gave the appearance that minorities could get elected to City Council while preventing Latino and African-American communities from achieving any lasting political power. It took until 2012 for Austin to choose another kind of politics.

While Butts has worked exclusively on local elections, his onetime ally Young took himself to a larger stage as a consultant for Gov. Ann Richards. In addition to successful runs with numerous state legislators, he also served as a Texas consultant for the presidential campaigns of Michael Dukakis and Bill Bradley. Young also dabbled in San Antonio politics, where he worked on a transition to a 10-1 system in which all 10 City Council members are elected from individual districts. It would become a model for Austin’s own reform.

In 2012 Young became an active participant in a city commission established to examine changes to the city’s charter. The group’s charge included a potential move from the at-large system to a geographically elected council. Young didn’t serve on the commission. But a former client, longtime state Sen. Gonzalo Barrientos, chaired it. And there were other friendlies, including local attorney Fred Lewis.

Butts did serve on the commission and so did familiar members of the Austin progressive establishment: former state Rep. Ann Kitchen, local activist Ted Siff and Susan Moffatt, the spouse of Austin Chronicle publisher Nick Barbaro.

Months of debate eventually boiled down to a vote over two competing proposals: a system that featured 10 geographically elected and two at-large council members, in addition to a mayor, and one that did away with the two at-large seats in favor of a strictly district-based body. On Feb. 2, 2012, the commission voted to endorse the 10-1 plan.

Later that month, the Charter Revision Commission delivered its report to the Austin City Council, recommending a single-member district plan and ending decades’ worth of race-based local politicking.

Austin City Council members, however, were not bound by the vote, and a faceoff loomed. Mayor Leffingwell signaled concern over the 10-1 approach endorsed by the charter commission in remarks delivered at his inauguration. There, Leffingwell also took the opportunity to endorse his own call for a system that retained some level of at-large representation. The Chronicle’s Josh Rosenblatt called Leffingwell’s statement “something of a surprise.” Rosenblatt wrote, “Foregoing the ceremonial niceties, Leffingwell described his plan as ‘much-needed reform’ while decrying the 10-1 plan proposed by Mike Martinez and Sheryl Cole as ‘worse than the exclusively at-large system we have today.’”

Cole and Martinez, you’ll remember, are sitting in the Council’s gentlemen’s agreement-reserved African-American and Hispanic seats. They—along with Leffingwell, as well as the rest of the sitting Council—are Butts clients.

Barrientos, Travis County Republican Party Vice Chair Roger Borgelt, and local NAACP head Nelson Linder—who also served on the charter commission and voted for the 10-1 plan—all got behind a now-citizen-backed effort to institute the 10-1 plan. Young was also an active participant in that effort. The group called itself Austinites for Geographic Representation and, conscious of where things could be headed at the council, its members began a petition drive to get their preferred version of geographic representation on the November 2012 ballot. They would eventually collect roughly 30,000 signatures.

The hybrid-ers—Austin establishment politicos who wanted to keep some form of at-large government—also formed a citizens group. They knocked two geographic districts off of the commission’s version of a hybrid-districting plan and began pitching an 8-2-1 proposal with eight single-member districts and councilmembers elected at-large. Both proposals went before Austin voters in November 2012.

For their part, Young and his colleagues suggested that the 8-2-1 plan—and the effort to place it on the 2012 ballot, led by none other than Butts—was intended to split the small number of votes expected on election day, and ensure that neither proposal garnered the requisite 50 percent, meaning neither would become law and the gentlemen’s agreement would survive.

To the surprise of some—not, says Young, him—the 10-1 proposal passed overwhelmingly, and the gentlemen’s agreement was officially no more.

The work of creating the 10 City Council districts fell to the newly created Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission—a body so entangled with rules intended to keep it honest that some worried whether it would actually have a large-enough pool of applicants. The commissioners also had to work fast to meet a December deadline (they finished in mid-November).

They have created a map that they feel will present a reliable African-American opportunity district, and some count as many as three Hispanic opportunity districts. But it remains to be seen whether the group has ultimately cracked the racial struggle that may continue to pervade city politics. Still, Austin City Council will soon see an influx of new people from parts of the city that were rarely represented at City Hall.

Butts isn’t thrilled with the outcome. “I look at numbers,” Butts says. “I question their assessment of numbers.” For Butts this starts with the decline of the African-American population and the coinciding rise of the Hispanic population in Austin. “Biology is history. You can ignore lots of things but you can’t ignore biology. Hispanics have a younger population, they have a higher birthrate than the Anglos and the blacks combined.” While Butts believes that he and the 10-1 coalition both want African-American representation on the Austin City Council, he isn’t sure that the 10-1 method is going to achieve that result.

“They’ve drawn lines…that Peck Young showed me,” he said. “What they did is that they are cutting all of the white voters out of what would be the black district.” This, argues Butts, would leave only African-American and Hispanic voters in regions of the city that could safely be called African-American opportunity districts—the places where the city’s African-American community could count on a chance at electing a representative of its choosing. “What they seem to fail to realize,” Butts says, “is that if you only have blacks and Hispanics primarily, the black population is in decline, the Hispanic population is [increasing]. Don’t get me wrong, blacks outvote Hispanics dramatically…but at some point, biology is history, and it will give away [the endgame].”

While he worries that the 10-1 plan will result in no African-Americans on the City Council, he also frets about the re-emergence of a previously endangered species—Austin Republicans.

“Republicans were behind 10-1 solidly,” he says. “They emailed, they sent out messages, their precinct chairs had signs for 10-1 in their yard, I know they did. They understood.

“[Republicans] are a nonfactor citywide. In an 8-3 system, you can create districts that would basically be dominated by Obama majorities in every case. In a 10-1 scenario, that is not as easy to do.”

He lays out this scenario: “Do you want one or two councilmembers—Republicans—running to the Legislature every time the City Council does something that they don’t like?”

At best, Butts’ partisan scenario is an interesting reflection of state-level politics. Texas Democrats have been shunted to political insignificance, some of it through creative gerrymandering, much the same way that Austin Republicans have a difficult time in local politics. And so, at worst, Butts’ argument reads like his own brand of voter disenfranchisement. Don’t Republican voters, even in Austin, deserve their own representation on City Council? Butts is certainly not alone, locally at least, in arguing that they don’t. That, of course, doesn’t necessarily resolve the issue here: Writing Republicans out of local politics may be satisfying, but it’s also just about as backward as, say, limiting minority representation to one or two seats on a seven-member body.

Butts divides the recent history of Austin politics into three major eras: the student movement of the 1960s, the progressive takeover of the city in the 1970s, and the greening of the city in the 1990s. He worries that a move toward geographic representation threatens the gains made by liberals in Austin even as the state Democratic Party floundered into irrelevance. Without citywide elections, will Austin remain as progressive a place?

Young points to San Antonio as a precedent, and to the emergence of Henry Cisneros, Leticia Van de Putte, and Julian and Joaquin Castro. “I know for a fact that [Mayor Castro] doesn’t [get elected without single-member representation]; neither does Cisneros.

“That’s one of the things Austin desperately needs,” Young continues. “There is a lot of talent that we don’t know about that Austin has squelched…because Austin has no way for those people to develop.” He believes Austin’s single-member districts will actually help Texas Democrats’ hoped-for resurgence. For years, Austin’s locked-in politics produced plenty of well-meaning, well-educated City Council members, but not one candidate who could win statewide.

“You are going to wake up some morning and some star is going to emerge, and they are going to emerge from some district where, if they didn’t have the ability to walk streets and raise money”—an impossibility in an at-large system in a city as huge as Austin—“they never would have been able to get elected.”