Vaya con Dios, Juan Gabriel

Mexico's most versatile singer and composer leaves behind a global legacy.

I come to praise El Divo de México, not to bury him.

Juan Gabriel, the most successful entertainer in the history of Mexican popular music, died August 28 at the age of 66 in Santa Monica, California, following a sold-out concert in Los Angeles. It was the first leg of his “Mexico es Todo” tour, which would have included various dates in Texas.

His remarkable story, including stints as a street musician, is now a new TV series — Hasta que te conocí (Until I Met You), co-produced by Disney Media Latin America. The series of 13 episodes premieres September 11, 8 pm CST, on the Spanish language Telemundo network.

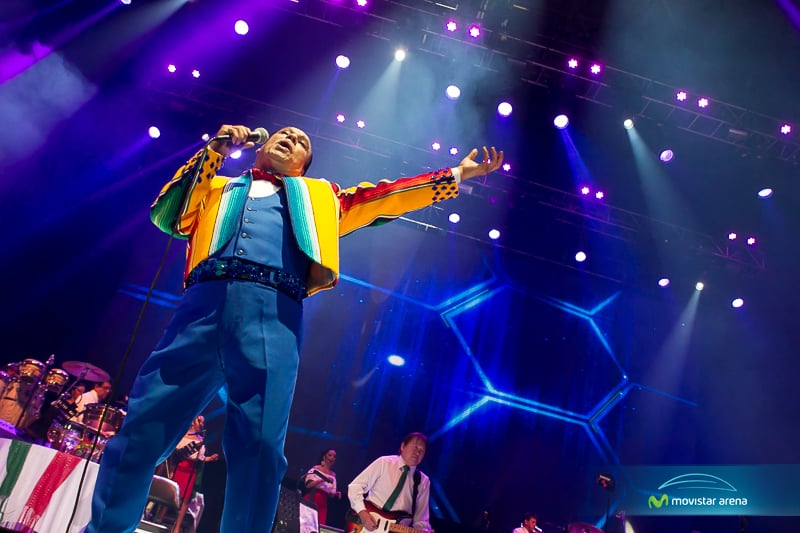

In the 1970s, his first recordings were top ten hits on both sides of the border. Tejano musicians were inspired by his then-fresh take on bringing corridos, mariachi, ballads and gospel-inspired choruses to his compositions and recordings. His concerts were hymn-like praises to Mexico’s culture when performed at charreadas (rodeos), while his stage shows were elaborate Las Vegas productions with a touch of Bollywood.

I lived in South Texas in the 1970s and would make weekend trips to the border towns of Laredo-Nuevo Laredo. My first stop would often be record stores, where I would search for his latest single or album. Border radio stations often programmed Elvis or the Beatles for an entire week. Ditto Juan Gabriel. However, they wouldn’t have to repeat any his songs, since by then he’d written 1,000 or more. By his death, he’d probably written another 1,000.

Most every Spanish language musical artist or group has covered a song by Gabriel — from Spain’s Rocío Dúrcal to Vicente Fernández to Tejano’s Kumbia Kings to Mexican rock bands the Jaguares and Maná. His original recordings are often part of quinceaneras, weddings, anniversaries and even funerals. At my mother’s funeral, his recording of “Amor Eterno” was played as our family said our goodbyes.

His hardscrabble life is the stuff of telenovelas. He was born in Parácuaro, Michoacán. His widowed mother put him in a boarding school when she realized she couldn’t care for him. He learned to write songs in his eight years at the school, before returning to live with his mother, by then in Ciudad Juárez . He got lucky, finding work performing at the club Noa Noa, which later became the title of a hit song and feature film in which he portrayed himself.

But he got his real break when the singer Enriqueta Jiménez Chabolla, more often known by her stage name, La Prieta Linda, introduced him to record executives. He changed his name from Alberto Aguilera Valadez to Juan Gabriel when he signed his first recording contract with RCA Victor. When I first met him, he was in litigation with the record label over the copyrights of his songs, which he had unknowingly signed away to the label. He later won ownership of his music and moved to a new record label.

In 1993, I interviewed him for a Spanish language magazine and a Mexico City daily. I spent a week at his small ranch on the outskirts of El Paso with a splendid view of the Franklin Mountains. He preferred living in the borderlands of El Paso, and when I asked him about his other house across the border in Juárez, he said he rarely spent time there. It was actually a mansion replete with chandeliers and a huge painting by Diego Rivera of Mexican film star Maria Felix.

“Actually I’m a bit of a nomad,” he said. “I’m always on a plane or a bus, but here, I feel at home.”

He hadn’t granted press interviews since 1985. At that time, he was devastated by a kiss-and-tell book, Juan Gabriel y yo, written by an ex-employee, Joaquín Muñoz. The author, who assisted Gabriel on tour for several years, suggested that the humble songwriter had succumbed to an international jet set gay lifestyle. Photos showed him embracing and kissing celebrities and fans, in particular, young male admirers.

Did he feel betrayed? “No,” he said. “I never read [the book].” (In recent years, Gabriel and Muñoz renewed their friendship. He never sued or denied the book’s revelations).

Despite being a vegetarian, his cook often made menudo with mushrooms replacing the tripe; he later suffered from diabetes, hypertension and being overweight. In recent years, his physician required him to rest for a month between concerts. He did neither. On the morning of his death, he was scheduled to perform that evening in El Paso. The coroner said he died of a heart attack and from exhaustion, along with other health issues.

And yet, in our interview, he’d said if he didn’t have to tour again he’d be very happy: “I was born to write and compose music. Period!”

In September, he was the subject of a three-day homage and celebration of his life and music at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico’s Carnegie Hall. Nearly a million fans paid their respects at Bellas Artes, where in 1990 he became the first pop musician to perform with the National Symphony Orchestra. In Ciudad Juárez, thousands passed by the urn with his ashes.

The presidents of both Mexico and the United States paid tribute to him. President Enrique Peña Nieto called him “One of the biggest musical icons of our country. His voice and talent represented Mexico. His music is a legacy to the world.”

President Barack Obama stated: “For over 40 years, Juan Gabriel brought his beloved Mexican music to millions, transcending borders and generations. To so many Mexican-Americans, Mexicans and people all over the world, his music sounds like home. His spirit will live on in his enduring songs, and in the hearts of the fans who love him.”

Toward the end of my interview with Gabriel so many years ago, I asked him about his legacy. “I have always loved everything that represents art. Wherever there is music, I’ll be there.”