Untangling S., Doug Dorst’s Novel within a Novel

A version of this story ran in the February 2014 issue.

What makes a book a book? When is a novel more, or less, than a novel? And how can you make those questions sound like anything other than the fragmentary revelations of a probably stoned sophomore essentialist?

We’re going to need to lay some groundwork. We’re going to be using the word “ostensible” more than usual. Buckle up and bear with.

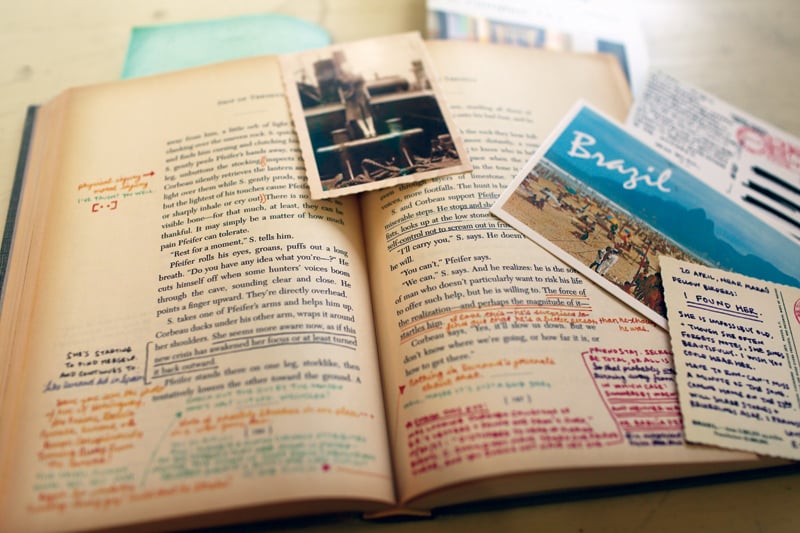

S. is the title of the book in question. It is a many-layered production, literally and figuratively. The outer layer is shrink-wrap; without it, browsers could just slide the book out of its cardboard slipcase—layer No. 2—and spill dozens of printed inserts onto the floor. These inserts—postcards, mimeographs, maps drawn on napkins, etc.—have been placed between particular pages for particular effect.

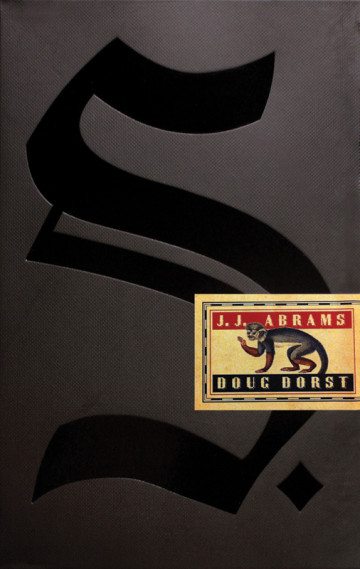

Layer No. 2, the slipcase, is the only place in this painstaking production where the words “J.J. Abrams” and “Doug Dorst” appear. S. was conceived by the top-billed Abrams—co-creator of the multivalent TV series Lost—and written by Dorst, author of the 2009 novel Alive in Necropolis and the 2011 story collection The Surf Guru, and currently a creative writing professor at Texas State University in San Marcos.

By J.J. Abrams and

Doug Dorst

Mulholland Books

472 pages

$35.00 Mulholland Books

Remove the slipcover and all traces of Abrams and Dorst disappear. Inside is a jacket-less hardback, apparently aged, its boards embossed in library-edition fashion with the title of the ostensible novel within: Ship of Theseus, ostensibly written by one V.M. Straka and ostensibly published by an outfit called Winged Shoes Press.

S., let’s note here, is a tour de force of the book-manufacturing art, from the Dewey Decimal sticker on its spine (813.54, i.e., American Fiction 1945-1999) to the cover’s bumped corners to the library stamps on the endpapers to the faux copyright page to the age-yellowed edges of the book’s occasionally coffee-stained 456 pages—all of it “ostensible.” Ship of Theseus looks and feels like what it’s supposed to be but isn’t: a well-worn library book.

Ship of Theseus was not written by V.M. Straka, and it was not published in 1949 by Winged Shoes Press, and you will not find it shelved at 813.54 STR—but here it is regardless, a self-contained novel with beginning, middle and end, further framed by an (ostensible) “Translator’s Note and Foreword” and footnotes throughout by the equally fictitious Filomena X. Caldeira. In these footnotes we learn that Caldeira—Straka’s longtime translator and apparent confidant, though the two do not appear ever to have met—has taken the liberty of completing Ship of Theseus, Straka’s final book, the manuscript of which was left incomplete in the wake of Straka’s apparent death, which Caldeira witnessed. (Or did she?) Where Straka’s words end and Caldeira’s begin is one of Ship of Theseus’ many collateral mysteries.

Ship of Theseus’ primary mystery—content aside for the moment—is the true identity of V.M. Straka. That’s the consuming focus of Eric, a former grad student at fictional Pollard State University who’s been expunged over some never-fully-explained contretemps between him and a professor who’s stolen his research, and maybe his girlfriend, and who’s racing to publish a book that will turn the world of Straka scholarship on its head. Eric has a ninja-like talent for invisibility and an intimate familiarity with the steam tunnels beneath Pollard State’s campus that allow him to slip unnoticed in and out of the university library, where he continues his quest-like research on the sly.

That library is where Eric “meets” Jen, a senioritis-stricken undergrad with a work-study job in the stacks. Which is where she comes across Eric’s personal copy of Ship of Theseus, left behind one night when Eric was forced to exit in a hurry. She picks it up and gets hooked on the story, and so begins a second, quasi-epistolary novel as Jen and Eric write notes to each other in the margins of Ship of Theseus, passing the book back and forth via a secret hiding spot in the library but never, until long last, meeting face to face.

This conversation between two readers takes the form of extensive multilayered marginalia: Eric’s original notes appear in faded pencil; longer back-and-forths between Jen and Eric are rendered in black or blue or green or orange or red ink—Eric’s in block lettering, Jen’s in cursive—the colors corresponding to various threads accreted over multiple re-readings. The two spar at first over his arrogance and her quickly diminishing frivolity, but their hackles lower as Jen begins to engage with Eric’s search for Straka’s identity, bringing her fresh eye and library-honed research skills to Eric’s experience-jaundiced pursuit. In bite-size notes they begin to share personal secrets and fears. Over the course of a conversation that amounts to a parallel novel all its own, they fall in love.

Meanwhile Ship of Theseus hurtles along around them, the story of an amnesiac—S.—abducted by the mute crew of a sailing ship that delivers him into adventures involving a weapons-manufacturing autocrat, shadowy labor-organizing cabals, secret islands, and a mystery woman known variously as Signe and Sola. Is protagonist S. a stand-in for Straka? Is Straka the writer also an assassin, among the many speculative identities attributed to him? Is there only one Straka, or is that name a front for a collective of writer/activists? Is Caldeira merely Straka’s translator, or something more, a relationship decipherable in her coded footnotes? Is theirs a love story, as Jen wants to believe, or a story of necessary sacrifice and dedication, per Eric’s interpretation?

In case you’re wondering, all this narrative trickery is delivered without the slightest whiff of postmodern razzmatazz. There’s a shell game going on here for sure, but it’s entirely in the service of an earnestly swashbuckling potboiler. Or two. Or three.

Props to Abrams for the elaborate conceit, but in execution, S.’s not-so-secret weapon is Dorst, who pulls off these multiple feats of high-wire ventriloquism without a stumble. There’s not a single line that threatens the illusion.

There’s also not a conceit in the scheme that’s entirely original. The wholesale invention of Straka-style most-interesting-man-in-the-world writers has been employed by authors as unlike as Robert Heinlein and Mark Leyner. An epistolary relationship developed in the margins of a parallel narrative underpins A.S. Byatt’s Possession, doubtless among others. There are echoes here of everything from Atlas Shrugged to The Bourne Identity.

And the Ship of Theseus, after all, is just another name for Theseus’ Paradox, which asks whether a boat that’s rebuilt, one plank at a time, until no original plank remains, is still the same boat. It’s a question about where—or whether—one can properly locate an object’s essential identity. It can be applied, if you want to get meta about it, to S.

If you complicate traditional definitions of authorship, do you still have a book? If the book you’ve invented has an invented book at its center, do you still have a book? If most of your book’s action takes place in handwritten notes scribbled in a fake book’s margins, do you still have a book?

Sure you do. As long as it’s got a reader, it’s a book. And if you can manage to reward that reader—as Ship of Theseus rewards Eric and Jen, and as S. rewards their real-life counterparts—you’ve got a book worth sharing.