Uncle Walter and Modern American Politics

A version of this story ran in the September 2012 issue.

As a young boy, the budding historian Douglas Brinkley followed Walter Cronkite’s nightly broadcasts on the CBS Evening News. The legendary, late broadcaster was the anchor for 19 years, until 1981. Like a lot of families, the Brinkleys of Perrysburg, Ohio, relied on Cronkite for the day’s news.

“That’s how I found out about the world,” Brinkley says. “I learned about civil rights, war, Watergate through Cronkite. I blocked some of that out as a professional historian, but growing up in the ’50s and ’60s, he was my babysitter; he was my information source. Whatever he said was considered the truth.”

Brinkley’s Cronkite, a wide-ranging, sharp-eyed, nearly 700-page biography, was published this summer.

A protégé of the late historian Stephen Ambrose, Brinkley, 51, has enjoyed a distinguished career as an author and educator and presidential historian. Brinkley is a history professor at Rice University in Houston and contributing editor at Vanity Fair, where he has written about figures in the pop-culture firmament such as Johnny Depp and Bob Dylan. In an interview earlier this year, Brinkley, who is based in Austin, told me that his subjects are unified by their “sustainable” participation in U.S. history.

Whether figures such as Depp will remain culturally relevant remains to be seen, but not Cronkite. Widely proclaimed “the most trusted man in America,” he was an irresistible subject for Brinkley. “It’s highly unlikely that we will ever see a Walter Cronkite again,” he says. “Television now, with satellite technology, and YouTube and the Internet, has made that notion that you’re going to have a person or one or two people that are trusted to distill news … part of the bygone days.”

In Cronkite, Brinkley covers the career highs and lows of the “Great White Father,” a term employed by Ben Bradlee of The Washington Post after Cronkite’s Watergate reports in 1972. Cronkite was born in Missouri but raised in Houston, where he was drawn to newspapers in high school. In the 1930s, he dropped out of the University of Texas to write about the Galveston nightlife. During World War II, he embedded with the U.S. military. Battle-hardened and professionally accomplished, Cronkite returned to Texas and joined the nascent CBS television network. His rise from cub reporter to international correspondent to heavyweight television anchor coincided with changes in broadcast journalism. Cronkite was part of an era when TV was defined by the Big Three: ABC, NBC and CBS.

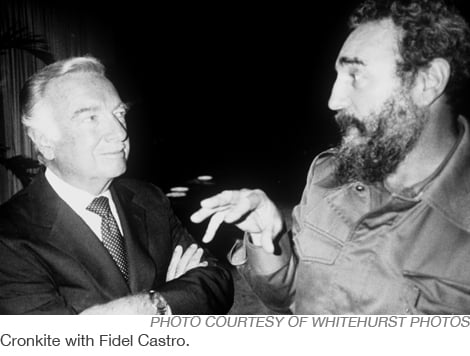

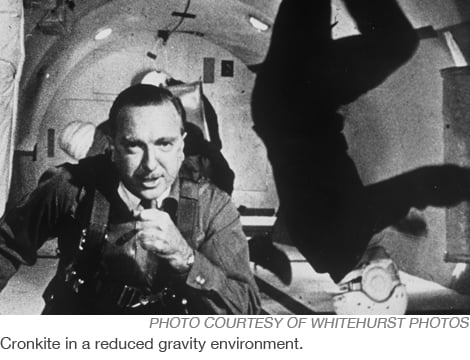

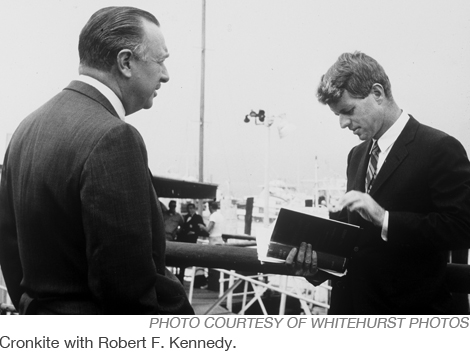

Brinkley delivers a blow-by-blow of many of the major events that shaped the second half of the 20th century in America and illustrates how Cronkite, in many ways, became the embodiment of the changes taking place in post-World War II America. He helped television news gain legitimacy, as Americans witnessed worldwide events from the comfort of their living rooms. Present for presidential inaugurations from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan, Cronkite also rushed to the broadcast booth that fateful day in 1963 when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. Baby Boomers may remember how Uncle Walter, an honorific given to Cronkite for his familiar presence, fiddled with his glasses before announcing Kennedy’s death. Cronkite also covered Vietnam, including the fall of Saigon, the civil rights movement and the U.S. space program. Many credited his coverage of NASA and the moon landing in 1969 with helping to heal the nation following the assassinations of John and Robert Kennedy, and Martin Luther King Jr.

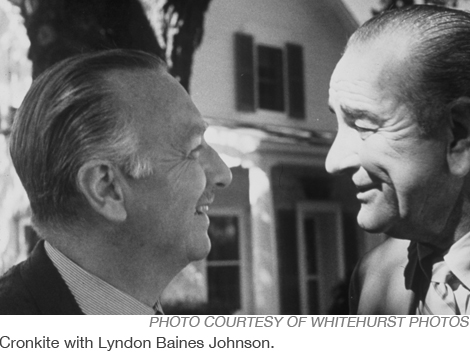

The book has flaws. Brinkley gives short shrift to lesser-known figures and historical anecdotes that might bewilder readers born after 1965. Still, in a tumultuous new era of 24-hour news augmented by social networking, Cronkite offers a timely reminder that journalists, pundits and politicians should aspire to more than Stephen Colbert’s “truthiness.” Like the elected officials he covered, Cronkite discovered early on that television was a political game changer, capable of galvanizing support for candidates and vulnerable to manipulation by savvy campaigners. Brinkley drives home these points in chapters dedicated to Cronkite’s relationships with various chief executives, especially President Lyndon Baines Johnson.

As the 2012 election comes to dominate the national airwaves, readers will find Cronkite’s historic role in televising the presidency especially resonant. Before he emerged as the leading anchorman of his time, the newscaster coached Sen. John F. Kennedy and U.S. House Speaker Sam Rayburn in how to look good on television, offering tips on makeup, manners, diction and wardrobe. Cronkite, who covered both Democratic and Republican conventions, paved the way for the electoral contest to become part of the television landscape. Simultaneously, broadcast news paved the way for national conventions to shift from selecting candidates to crowning them.

During an interview, Brinkley offered further insight into this dramatic change. “Anybody who thinks you’re going to have a brokered convention, they know nothing about politics,” he explains. “TV killed the brokered convention in 1952, and it gave birth to our modern caucus and primaries. The primaries are the sausage factories. Two months before the election what you see isn’t a nominating process, it’s a coronation done with the trappings of whistles, balloons and smiles for public consumption.”

Critics have taken issue with Brinkley’s analysis of Cronkite’s impact in other areas, however. The author is on shakier ground when it comes to the impact of the newsman’s famous 1968 Special Report broadcast, during the bloody Tet Offensive in Vietnam, when the Viet Cong overwhelmed U.S. and South Vietnamese military positions. In the July 9 issue of The New Yorker staff writer Louis Menand argues that Cronkite’s declaration that the war was “mired in stalemate” did not have the influence over LBJ that Brinkley claims it did. Brinkley revisits the story that after the divisive broadcast, President Johnson declared: “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost the war.” In his article Menand, who criticizes Cronkite and the book, says: “The trouble with this inspiring little story is that it is either invented or disputed.” Menand cites a variety of sources, including Cronkite’s own 1996 autobiography, as evidence that Cronkite’s report did not drive foreign policy.

In his book, Brinkley notes that the LBJ quote is mired in “scholarly controversy,” but claims regardless that Cronkite “grabbed America’s attention about Vietnam in a way that would have been impossible for LBJ to have missed.”

Brinkley writes: “That single CBS New Special Report guarantees [Cronkite’s] status as legend.”

Here, Brinkley comes under fire from journalists and historians for appearing to stake Cronkite’s importance on that special report, rather than on the overall impact of his legacy. For example, when Richard Nixon became president, Cronkite and his colleagues at CBS encountered a much more disdainful bunch in the White House, with Charles Colson, special counsel to the president, helping lead the charge against the press. Forty years before anybody heard of the tea party, Vice President Spiro Agnew was attacking the liberal media, complaining about East Coast elites. Although Cronkite never landed on Nixon’s infamous Enemies List, he and his colleagues were embroiled in a running battle with Tricky Dick.

Brinkley concludes that speaking truth to power made Cronkite a beloved figure among his fellow journalists and television viewers. Nonetheless, Cronkite was criticized by some journalists for asking softball questions, and didn’t always hammer home the toughest points. The newscaster was neither the first nor the loudest critic of the Vietnam War, and he didn’t wade into the mess of Watergate until The Washington Post made a solid case that crimes had been committed. Questions surrounding conflicts of interest and some less-than-savory aspects of the early days of television news—a junket here, the editing of an interview there—do damage to Cronkite’s reputation. But Brinkley says that Cronkite really did aim to serve the public good.

The newsman didn’t forget his Texas roots. His connections in Austin and Houston paid professional dividends, according to Brinkley, especially after LBJ became vice president. Indeed, whatever the fallout from Cronkite’s on-air foreign policy analysis, the two stayed in touch well after television ceased to bring Vietnam into households across America. “It didn’t hurt Cronkite having been from Texas to suddenly have Lyndon Johnson in the White House from ’64 to ’68. In fact, the last interview that LBJ gave was with Cronkite—again, because he had the Texas ties.”

Freelance writer Dan Oko lives in Houston, where he is a contributor to Houston magazine. His work also appears in Garden & Gun, Audubon, and Texas Highways. In 1981, when Dan was 13, his stepmother gathered the family to watch Cronkite’s last nightly newscast. That’s the way it was.