Top TPPF Analyst: Coal Ended Slavery

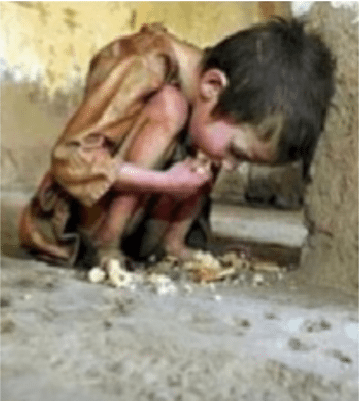

Above: This is your family on fossil fuels...

This is a blog about Texas politics, so let’s talk about textile factories in the north of England, and the strong message they send about the total inability of our state’s most significant policy organ to handle cognitive dissonance. Bear with me for a second. (Or for a few minutes.)

Last week, Houston played host to a high-profile conference on energy issues, convened by the Texas Public Policy Foundation, which no less a source than Wikipedia describes as a “think tank.” It is the most influential such entity in Texas. The group, with the help of a great deal of corporate money, has the ear of the governor and much of the Legislature. What its legion of analysts say and do matters a great deal to the way Texans live. Sometimes they do valuable work. Sometimes they do bad work.

This being Texas, a respectable think tank needs Big Ideas about energy. The group’s message for the most part—and the message of the Houston conference—is that fossil fuels are Good, and we should use more of them. Even global warming is good, if you look at it in the right light, if you were to stipulate that it’s even happening, which it isn’t.

At TPPF, this wholesome message is mostly propagated these days by Kathleen Hartnett White. Before TPPF, White led the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality from 2001 to 2007. If you lived in Texas in the last decade, it was White’s ostensible responsibility to safeguard your lungs and general well-being, and to carefully weigh and balance those concerns against the demands of economic development—a weighty responsibility.

White has become an energy analyst at a fascinating time. Here’s the crux of Texas’ problem: We’ve discovered a new ocean of gas and oil under the state, which can make a significant number of people here—and to a lesser degree, our cash-strapped state in general—very rich. At the same time, the scientific community is more sure than ever before that burning those fuels will hurt us in very real ways. Some of us can live large now, but many others will pay a heavy price.

How can we navigate these complex questions? Into the rain-sodden arena of doubt drives White, in a coal-rolling Humvee upon which another Humvee has been delicately stacked, like a pair of mating dragonflies. Other conservative thinkers have questioned the economic efficiency of renewable energy. That meeker argument is becoming less powerful every day—even though White still calls renewable energy “parasitic,” unlike, one supposes, the heavily subsidized fossil fuel industry.

White’s flooring the gas pedal. Her magnum opus, “Fossil Fuels: The Moral Case,” takes the position that burning coal and oil is in fact a moral imperative. Coal and oil—cheap energy—led to modern prosperity, White writes, and turning away from them will reduce access to prosperity here and across the globe, with grave consequences.

It’s an odd argument partially because it’s hard to say what it stands in opposition to. As a contribution to a policy discourse, its existence only makes sense if you believe—as many do, apparently—that environmentalists desperately desire to tear down the power grid and return the human race to agrarian penury.

The question of balancing prosperity with environmental responsibility in poor parts of the world has been a constant subject of debate and discussion in the environmental movement for decades. And the role that coal played in the story of the industrial revolution isn’t exactly contested territory. Furthermore, coal’s role in the creation of modernity says nothing about our ability to find new sources of prosperity—if we, with our amazing ingenuity, built the combustion engine, why can’t we build a better one? Renewable energy is already bringing electricity to parts of the world that have never really had it before—in places like Tanzania, solar panels are a much better option for rural communities than connecting to the inefficient, poorly maintained national power grid.

But White’s been getting a lot of play with the paper—she’s done the rounds with it this summer. White was the star at the climate conference last week, where Rick Perry deigned to speak. And she’s proud of it: When White presented her paper at the Heritage Foundation in June, she told the crowd that writing the paper led her to “some fascinating books,” and that her curious wanderings included the discovery of “a jillion papers in academic journals.”

But her footnotes come from a mix of places: They range from the British tabloid The Daily Mail, an authoritative source on nothing, to the 17th century English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes. White re-reads Hobbes’ Leviathan and concludes that his theoretical concept of a pre-society, pre-government “state of nature” accurately depicts “preindustrial conditions for the average person.” Hm. There are actual journal articles—mostly from other think tankers. But there’s also reference to less auspicious sources.

It’s a beautiful distillation of a worldview that shuns complexity in all forms.

The paper contains extensive block quotes and citations from The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves, a 2011 popular science book by Matt Ridley—otherwise known as Matthew White Ridley, 5th Viscount Ridley, a Conservative Party member of the United Kingdom’s House of Lords. In some circles, Ridley is most famous for helping to tank the British bank Northern Rock, where he served as chairman. Northern Rock’s spectacular implosion in 2007 was one of the precipitating events of the global financial apocalypse. Several years later, Ridley was awarded the Manhattan Institute’s Hayek Prize, for his ongoing contributions to the unimpeachable cause of the free market. In other circles, Ridley is most famous for his viral Ted Talk, “When Ideas Have Sex.” Ridley gave a keynote at the Houston conference.

But in lieu of a longer dissection of the paper, let’s consider White’s weirdest extrapolation of her argument. On page 17, she notes that the abolitionist movement in Britain happened concurrently with coal-fired industrial growth, and posits that the rise of factories “indeed increased and institutionalized compassion.”

In a post on TPPF’s website called “Energy and Freedom,” she expands on her case:

First harnessed in the English Industrial Revolution, fossil fuels spawned unceasing economic growth-an unprecedented productivity of most benefit to the poor until then consigned to poverty and enslavement across the world.

In 1807, the British Parliament finally passed William Wilberforce’s bill to abolish the slave trade in the British Empire. In the same year, the largest industrial complex in the world powered and illuminated by coal opened in Manchester, England. Thus began the century-long process of converting mankind’s industry from the power of muscle, wood, wind, and water to stored solar energy in fossil fuels.

Fossil fuels dissolved the economic justification for slavery.

There’s some bad history in this passage, but it’s so much more than that. It’s a beautiful distillation of a worldview that shuns complexity in all forms.

Sure, there’s a discussion to be had about the reasons for the success of abolitionism in England. Was it a political and social movement, emerging from the Enlightenment, which succeeded in advancing a moral case, or did it happen merely for economic or practical reasons? At any rate, black Britons like Ignatius Sancho and Olaudah Equiano, who were seminal figures in the movement, were active decades before the period White describes. The major first touchstones in the eventual abolition of slavery in the British Empire happened either well before the industrial revolution, or at a point when the industrial revolution was in its absolute infancy.

But the key thing: In tying the abolition of the slave trade to the growth of industrial Manchester, White gets it exactly backwards. The fossil-fueled industrial revolution she’s describing didn’t “dissolve the economic justification for slavery,” it made slavery more lucrative. It made slavery worse.

Here’s why: the new factories in England White describes were producing manufactured goods. Incidentally, many of them—along with many of the touchstones of the industrial revolution, like James Watt’s steam engine—were financed with money from the slave trade. But those factories, most of which were producing textiles, needed raw materials. Foremost among those raw materials was cotton.

Manchester’s new ability to make cheap clothes for the English working class meant that the factories needed a lot more cotton—so demand for the blood-drenched crop exploded. Manchester’s industrial growth was enabled by slavery—something people in the north of England are well aware of. And it fed slavery, too. True, Britain outlawed the slave trade in 1807—but they kept slaves in the colonies until 1833. Afterward, they depended on American slavery. When the fruit of American slavery was finally disrupted at the points of the bayonets of the Army of the Potomac, Northern England plummeted into depression.

As industrial Manchester grew, the American institution of slavery ballooned in scale and scope. In 1800, American slaves produced 156,000 bales of cotton—in 1860, they produced more than 4 million bales. From 1790 to the start of the Civil War, the American slave population likewise multiplied from 700,000 to 4 million, due in large part to new industrial efficiency facilitating demand for cotton—including American contributions like the cotton gin.

Take the words of South Carolinian Thomas Cooper, who warned the British about the price of abolition in 1838. “Every slave in a southern state is an operative for Great Britain. We cannot work rich southern soil by white free labour,” Cooper wrote, “and if you will have Cotton Manufacturers, you must have them based upon slave labour.”

So White got it exactly backwards: The coal-fired industrial revolution exacerbated the problem of slavery. Does that mean that fossil fuels are evil? No, that would be extraordinarily silly—as silly as saying the opposite.

What it does show is that development is a double-edged sword. Things are almost never wholly good, or wholly bad. They’re complicated. They embody complex trade-offs. They have unintended consequences. That’s what the people of Texas asked White to consider when she was the head of TCEQ.

The environmental problems we face today—they are vast, and time for consequential action, knowledgable people tell us, is running short—are very complicated. Texas, as a capital of sorts for global energy development, has an outsized role to play in either our success or failure to cope with them. The people of the state deserve better than meager propaganda. At last week’s summit, in the belly of downtown Houston, White and colleagues got the space to explain to some of Texas’ more powerful people that “America’s energy is the right and moral solution” to the world’s problems.

Modernity—medicine, travel, leisure—is a nice thing. Slowly cooking the planet is not so nice. Helping us navigate trade-offs—taking the measure of the good and the bad of an issue, and finding a path that takes the most of the former and the least of the latter—is the highest possible service intelligent people in public life can render. If think tanks have any role to play, it’s that. But don’t go looking for it at the Texas Public Policy Foundation.