They Die in Brooks County

As border security tightens, South Texas becomes a graveyard for the weak and the unlucky

At the Side Door Cafe in Falfurrias, Texas, body counts enter conversations as naturally as the price of feed, or the cost of repairing torn fences. “I removed 11 bodies last year from my ranch, 12 the year before,” said prominent local landowner Presnall Cage. “I found four so far this year.” Sometimes, Cage said, he has taken survivors to a hospital; mostly, however, time and the sun have done their jobs, and it is too late.

As increased U.S. border security closes certain routes, undocumented migrants continue to come but squeeze onto fewer, more dangerous and isolated pathways to America’s interior. One of these is the network of trails that bypasses the last Border Patrol checkpoint traveling north on Hwy. 281, in Brooks County. That change is having a dramatic ripple effect on the county (total pop: 7,685), and on people who have lived here for generations.

For one thing, the dead are breaking the budget. County officials earmarked $16,000 in fiscal 2007 for handling deceased indigents. That category includes the remains of undocumented Mexicans and other would-be migrants found within county lines. But by May, Brooks County had already spent $34,195 on autopsies and burials, “and we’re just heading into the hot months now,” said County Judge Raul Ramirez. It’s also rattlesnake mating season, noted the judge, who grew up on the King Ranch. It’s the time when the serpents move around most, biting the unwary and those who walk in grass and sand without high boots.

“Don’t get me wrong. I’m glad to do this. I’d spend $120,000 if I had to because it’s the right thing to do,” Ramirez said in his modest office on Allen Street in Falfurrias (population 5,020), the county seat. “But we could be helping more of our own.” About a third of Brooks residents live below the poverty line; average household income is $21,000; jobs are just plain scarce.

Pictures of the dead are kept discreetly in certain places in this town, a collective album that tells an important part of what Brooks County-which used to be better known for oil, watermelon, and a Halliburton facility-has become in the last couple of years: a grave for the weak or unlucky. The local Minuteman-type militia, for instance, has a collection of matted 11×14’s. Some are artful: a skull amid crawling vines, a kind of meditation; a young man’s figure with legs softly bent, his head thrown back against a bush with the arc of a ballet dancer’s neck-only an accompanying close-up of the winsome face, mouth open and vacant eyes, speaks death. Some remains are partially clothed. There is a condition that comes with too much sun: judgment wanes, and the affected person mistakenly believes stripping will assuage the heat inside. Many fallen dead from dehydration are found with jugs of water lying nearby; the inexperienced trekker-especially when lost–will save water instead of sipping it periodically, until a line is crossed in the brain and the person no longer feels thirst even as he is expiring from it. Among the pictures are corpses bloated so grievously they look ready to pop. The body of one young woman is not badly swollen, lying with face and torso intact, but her legs have been gnawed down to the long bones by a feral pig.

Luis M. Lopez Moreno, Mexico’s consul in McAllen, said there are other changes that may add to the death toll. Since the border has become so difficult to cross, working men who moved back and forth annually are now stuck in the north, and family members unaccustomed to the trek are “trying to reunite” by traveling to the States. Women, arguably less able to withstand the journey, sometimes caring for children, are represented more in the migrant stream. Young migrants, the majority of those who come, are likely to be better educated and more urban now, less aware of how to manage themselves under extreme conditions.

“Hank,” a guide for high-end hunters who doesn’t want his real name used, thinks he saves lives. Unobtrusively, he turns hunters’ blinds away from nearby trails so the “illegals” don’t get shot by accident. This is also an attempt “to protect the psychological state of the hunters.” They may be men fearless in high finance and politics-Washington figures including both Bush presidents have hunted here, with Air Force One parked incongruously on the county airstrip. And the gentlemen may have the confidence big wallets can bring, paying well over $1,000 a day to stalk deer, spring turkey, quail (reportedly Bush One’s favorite), wild pig, and imported exotic animals, and to stay at lodges with gourmet meals, bars, and wireless. Surprised in the wild by local human traffic, however, they can quake.

“Hunters, they get scared and panic, especially if it’s something like a group of 30 coming through,” Hank explained. “The illegals got so bad last year we had to buy two-way radios.” Hunters can use the radios to call their guides for help. Hank’s job has changed in other ways, too. “Before there was downtime to be in the truck, kick back, park in a pasture, and wait for the hunters.” No more. “We stay within 100 yards.”

Hank once discovered a man lying on his back, one hand on his forehead, knee up, as if he were resting. He had been cooked in place. Another body fallen in the middle of a trail had a path worn around it, where migrants stepped to avoid the corpse. Last Thanksgiving, he found one with “still a little meat on the head, but the arms and legs were detached, pretty much just bones, lying nearby.”

At home, Hank reaches into the bed of his pick-up and pulls out a black backpack like the ones he finds “most every day.” Inside are dirty clothes, a comb, deodorant, a razor, mirror, a pair of tweezers. It’s typical of a pack left behind as a migrant emerges at a highway pick-up point, ready to blend in to America. Inside the house with his wife and two small children, Hank displays a silver-handled .380, which he started carrying only recently for protection, after 14 years on a job he used to love. Coyotes, those who guide the migrants for high fees, are vicious, he says. That’s a good reason for not wanting to use his real name. They’re not just from Mexico but are homegrown too, some from right here in town (see sidebar). But that’s nothing compared to gang members he began to see two years ago. MS-13, he said, tattooed from head to toe and skinheads. Unlike other illegals, “they never talk to you.” Hank never expected to see the kinds of things he sees now, and reluctantly plans to move on to another job someday, although he would like to spend a few more years at this one. “If I can last,” he said.

Brooks County is some 70 miles from the U.S.-Mexico border. The checkpoint here tallies more interceptions and drug confiscations than any other in the nation. Migrants are either dumped just south of the checkpoint by coyotes, or they reach Brooks after walking all the way from la linea, which takes about 60 hours. They enter the ranches and desert stretches, avoiding the checkpoint until hours later – ideally for them – they reach highway pick-up spots around the town of Falfurrias or nearby ranches. The local Minuteman-type group calls one path west of 281 the Ho Chi Minh Trail because it’s so heavily traveled. Other trails traverse hot sands, or in winter are mercilessly cold and wet. (One man found dead in a barn on Christmas Eve had tried to use feed sacks to keep warm.) The unfit, those held back by children, the old, and anyone else who can’t keep up the brisk pace, are at risk. Coyotes don’t wait. A kind of frontier law forbids those lost and left behind from attaching themselves to another coyote’s group. This stark and stunning landscape, this once-welcoming town far from where immigration laws are made, is where the reality of U.S. immigration policy, or lack of policy, plays out darkly, in a way almost invisible to the outside world.

“We haven’t got any input in policy,” said Judge Ramirez. “The problem is here but you don’t look here. How many politicians come here?”

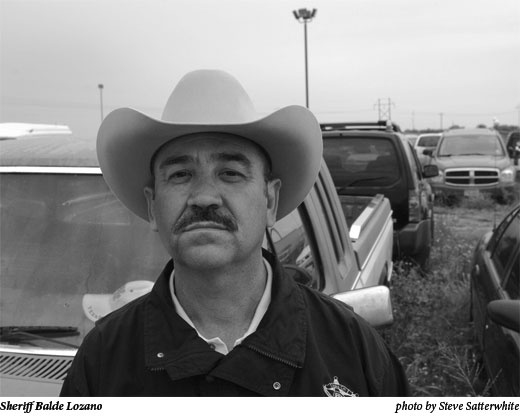

“Washington, D.C., and even Austin don’t have any idea what goes on,” said Brooks County Sheriff Balde Lozano. “Worst is the deaths. We get there and sometimes they’ve been dead minutes, sometimes months. Some I’m sure are never found.”

Lozano’s office adjoins a parking lot where hundreds of confiscated cars from smugglers wait to be sold at auction. There are flashy sports models, family sedans, beat-up vans, new pick-ups. Some are painted with phony company logos. “It’s gotten worse, that’s for sure,” said the sheriff. “There were always people walking. Now more vehicles are carrying people. There’s more money in aliens than drugs now.” The seized vehicles are Sheriff Lozano’s source of funds to pay for night vision binoculars ($4,000 a pair) and a new jail. They also buy patrol cars that chase coyotes after “bailouts,” the drop-offs and pick-ups that become frenzied and perilous when drivers realize they’ve been spotted, and migrants jump and scatter. But Lozano says the band of counties like Brooks well north of the border is “a haven for illegals” and deserves attention from those in Austin doling out funds for border enforcement.

“They don’t know what we do here, how many vehicles we seize,” said the sheriff. He refers indirectly to Operation Linebacker, Gov. Rick Perry’s border security program created by the Texas Border Sheriffs’ Coalition, which last year distributed hundreds of thousands of dollars to each of the coalition’s 16 member departments. But nothing came to counties like Brooks. “It’s out of hand. They may be the linebacker but we’re the receiver,” said Lozano. “What about the border 100 miles inside?”

Police Chief Eden Garcia put it this way: “We should be included because the brunt of the force is coming through our communities. They’re being housed in our communities and you better bet the chases are dangerous.” (Both police and sheriff’s departments have a policy of no pursuit. Spooked coyotes speed anyway.) The Falfurrias Police Department has its own lot for seized vehicles; last year they brought in $125,746. “Backpackers” is the name for small-time runners who go around the checkpoint carrying dope, “marijuana and coke, nickel and dime stuff,” said Chief Garcia. But for the police too the big issue has become human traffic, because more who want to make a buck are turning to it. “We’re not talking about drugs any more. Every car we stop is immigrants. It just pays more.”

Lourdes Treviño-Cantu still calls them “travelers.” Treviño is a descendant of Ramon de la Garza himself, one of the county’s earliest settlers, who came in the day when tracts here were still granted by Mexico and Spain. Customarily, when passing migrants asked for food, Treviño’s mother would slip inside the house, make a stack of tortillas, and take them out to the hungry travelers. But things have recently changed. “If it was the immigrants of old there’d be no fear; you’d live and let live. If they wanted to improve their lives that’s fine. Before, the travelers came alone or with one or two of their family, and they were humble, polite. Now they come in packs. They’re desperate, bold. A lot of them are pretty well dressed, and everyone seems to want to go to Houston. It’s a completely different element.”

Analysts and townspeople agree the vast majority of migrants are Mexicans who are very poor, or slightly less than poor and looking for a better job, or attempting to reach family. According to Sheriff Lozano, however, the first identified MS-13 gang member among the migrants was caught in Brooks County. Coyotes often have criminal records. Lourdes Treviño’s extended family is more cautious now on the homestead, she said. A sister is constructing a fence around her house perimeter, a first for them.

Small habits, the kind that make up the comforting weave of a life one knows, are changing. Corina Molina, the county auditor, used to come out to the driveway in the mornings and start her engine while she returned inside to gather up a child, or exchanged pleasantries with neighbors doing the same thing. Since an undocumented migrant under pursuit grabbed one of the running cars and took off, the women of the neighborhood dropped the custom. Another county employee, Katy Garza, said she had witnessed a police action that very morning at one of the safe houses used by smugglers to keep migrants overnight. “I guess I’ll be having to lock doors now,” said Garza. “I have a granddaughter who plays out front – maybe that will have to change too.”

Two women professionals in their fifties did not want their names used because-like “Hank”-they feared retribution from local coyotes if they spoke to a reporter. Locals who collaborate with the trafficking network are few, but “it’s a small town,” neighbors say, and some do not want to cross others they grew up with, or recognize on the street. “I thought with the National Guard on the border it would be okay, but the number [of migrants] is growing, and now I won’t stay home alone,” said one, an accountant whose home is in a rural area. She had her refrigerator raided, and shampoo swiped, but no jewelry or money. A few weeks back young women emerged from the brush and approached her husband, a backhoe operator, begging rides to Houston. Returning late from a party with office companions, all women, the accountant said she “realized something else new.”

“Nobody wanted to go out and open the gate alone,” she said.

The other woman said she recently answered the call of a man standing outside with a Bible, asking for food. “When I turned around 20 people with him came out of the woods,” she said. “My life’s changed. I don’t want to get raped. I’m afraid.”

Ninety-two percent of Brooks County’s population is Hispanic, and even most blue-eyed Anglos are bilingual from the time they are toddlers. It’s a culture that used to feel more connected to the immigrants coming through, documented or not, or at least not feel alien to them, because as Police Chief Garcia put it, “A lot of our families came the same route.” But the greater number traversing the county now and the mischief this does to property, and a suspected criminal element that has slipped in among them, is straining that culture.

Presnall Cage grew up on the family ranch, 46,000 acres of it. “We had them come through for years, agricultural workers, only men,” he said. “They hailed you and asked, ‘Do you have work or food?’ They walked, all the way from Mexico, singly, or maybe in twos, and they knew where the cowboy camps were, where they could pick up some coffee or a meal. Six months later we’d see them walking back, going home to join their families.” Today big groups pass through the ranch, he said, and the guide has a cell phone and GPS. Cage spends more than $50,000 a year to repair property damage caused by the migrants, who bend or cut fences, break pipelines to get water, and leave gates open, which means cattle stray or get mixed up. His cowboys-and this isn’t the job they signed up for-go out Fridays on litter patrol, collecting hundreds of pounds of plastic bags, jugs, backpacks, and other detritus. Cage thinks back to the old days, before the recent immigrant surge, and looks thoughtful. “We never had a body, all those years.”

One bright afternoon Dr. Michael Vickers, veterinarian by profession and founder of the four-year-old Texas Border Volunteers, a civilian group, tears across two lanes of oncoming traffic and skids into the sandy drag just short of a ranch fence. He had spotted a black Suburban with darkened windows pulling away, the kind a coyote might drive. “There’s 12 sets of tracks here,” Vickers said with the eye of a lifelong outdoorsman. We’re a mile south of the tower that marks the Falfurrias checkpoint. He calls some Volunteers to watch for “the perps” at the other end of the fence line, miles away. It’s full sunlight. “They’re brazen,” Vickers said. He blames unscrupulous employers, the U.S. and Mexican governments, and the vile coyotes most for the mess, but he doesn’t tolerate migrants who came to America illegally.

Along the highway, ranch fences bend where migrants climbed over them or crept underneath. T-posts slant at crazy angles, markers for human traffic. At one spot a 10-foot stretch of fence curves to the ground, clearly not a crossing for only one or two people. “That’s a horde,” Vickers says. We turn onto a caliche road, beach buff in the glare and throat-scratching powdery, traveling deep into Vickers’s own ranch. Four whitetail does raise their heads. We travel the petroleum pipeline, one likely path. He says to keep an eye on the bush line too, because the aliens hug it. “Once they get into that heavy canopy it’s hard to see them.” Like some other ranchers, Vickers has installed a faucet near a windmill and painted it blue to make it easier for trespassers to find and drink from easily. Partly it’s a humanitarian gesture, partly an economic one. Thirsty people break the floats and water runs out, burning a holding tank’s submersible pump. Repair cost: $2,500.

The Texas Border Volunteers, most of them armed, track and surround migrants and coyotes. They’re better equipped than local lawmen, and partly funded by ranchers, they say. Their stated aim is to communicate the location of illegals for authorities, “to report intel to the Border Patrol.” They reckon 1,000 people come through daily, a number used by other sources, and only some are captured by the undermanned agents. “What gets me is their total disregard for our property, for state and federal laws,” Vickers said of the “aliens.” “I don’t blame them for wanting to come, but do it legally. I’m mad. They’re stealing our country.”

Mike Vickers is well regarded locally, with a clinic and membership on a statewide animal health commission. He has some national fame, too: It was Vickers who originally isolated the “Ames” strain of Bacillus anthracis used in the deadly anthrax attacks of 2001. His 200 Volunteers come from across Texas and beyond, and include former law enforcement and military personnel. Especially at night, and particularly during a full moon, they fan out on horses, in white trucks and camouflage-painted ATVs, to operate on private property with landowners’ permission. His Falfurrias ranch is in the “pick-up zone,” off Hwy. 281 north of the Border Patrol station. In September an unclothed woman was found dead on his fence line. Some women leave groups to avoid assault, he said, and just don’t make it to safety. Vickers’ wife Linda once whipped out her Browning .380 to pin down a Brazilian migrant following her from the cabana to her house. “You’re hosed if they have bad intentions,” she said. “So you’ve got to make a decision about who they are within 20 feet even if you’re armed.” Once, said the couple, their dog appeared carrying a human skull.

Sheriff Lozano said that for civilians to surround migrants might be detaining them against their will, which could be against the law, “but no one has complained about it.” Vickers admits the Volunteers dressed in camouflage appear like enforcement authorities, and the presence of the dogs they take with them is intimidating. But the aliens are technically free to keep walking, and if they don’t know that, well, too bad. The Border Patrol says it doesn’t encourage private citizens to do its job, which is dangerous.

But the Volunteers claim they disrupt coyotes’ deliveries of human beings, save lives by finding the lost and straggling, and are on the spot to receive anyone who wants to “surrender” because they can’t go any farther. Most of all, the Volunteers want the feeling they are doing something about uninvited newcomers.

Near 9 p.m. the operation begins. Cell phones off. Earpieces fixed. Radios clipped to belts. Scouts leave. Others deploy. The equipment in the vehicle in which I ride is hand-held. Night vision goggles make the panorama green and bright; every object is clear, but green. We overhear communications between Volunteers with handles “Cap” and “Rocky,” and the driver reports our own concealed position to base. The Volunteers have 500 GPS points in the area as references; response can be quick. The thermal imaging equipment sees through the dark too, the tree line clear, mesquite feathery. It’s a matter of looking for movement-people lying flat can’t be picked out among warm stones. Standing flush against a trunk, they’re invisible. Thermal tracking makes the surrounding world not green but black and white-whatever holds heat gives off a glow, so you can follow the very roots of trees, gnarled and continuous in the cool ground. Far off a Border Patrol helicopter drops a spotlight on the ground, the shaft faint at this distance. Close by, tree trunks look eerie because they are white. They look like winter, or like birches instead of oak, or dead. It takes time to tell the difference between a rabbit and a hunched figure that might be a man. It’s magical in a way, the new eyes, the tangle of glowing lines and curves that transform themselves into deer with antlers looking soft, lolling in the sage. Catching moonlight.

But that’s not what the Volunteers come for. Once you make out what you are seeing, and it’s not a migrant moving toward his destination, unaware he’s being watched, the idea is to keep scanning, keep looking….

In McAllen, Consul Lopez Moreno says the Mexican government supports a temporary worker program of some kind because it revives a system that worked well until the big U.S. immigration reforms of 1986 and 1996. “This was a revolving door. The United States opened or closed it as it needed,” said Lopez. “Breaking the cycle is what has caused the problem.” That “circularity”-when workers went back and forth more easily between labor in the States and family in Mexico-worked for both countries, he said. The United States needs workers. Mexicans need work. “But this way they’re candidates for death,” he said.

One-third of the consul’s staff works in the Protection Department, which handles searches for those reported missing by families in Mexico, and repatriation of the deceased. It’s a job that takes a daily toll, and McAllen is classified for diplomatic staff as a hardship post. José Luís Diaz Mirón Hinojosa, who goes to the field when remains are found, now attends 40 to 50 cases a year. “I can give certainty to people,” Diaz says, returning the bodies of the missing. At least the dead from Brooks County are easier to identify than some-about 80 percent can be sent home; around the Rio Grande the percentage is fewer, because remains deteriorate faster in the river.

The operation for matching data about the missing with data about the unidentified dead takes place in a small room at the consulate. One afternoon a dedicated HP computer has the words “mujer Falfurrias” fixed on the screen. It refers to identifiers of a dead woman: where she was found, the shape of her face, her mouth, her eyes. It’s a public access system. Mexicans can check it, and perhaps match it to someone whose phone calls have stopped, or who have otherwise disappeared. A family can also initiate a search by filling out a form online and sending pictures, often a school or party photo.

Staff in McAllen photograph clothes of the unidentified deceased, faces, belongings, and the body itself, to help the family. “We try to be sensitive to the people,” said Vice-Consul Sandra Mendoza. She may call a community telephone in a village, for instance, to contact a family of someone found dead, whose characteristics match someone who has been reported missing. She will instruct a family member to go to the Foreign Affairs Secretariat’s computer in a nearby city to view the information or picture. Don’t send a father or mother, she will caution. Mendoza shows me a photo of a cadaver just taken from the river. Young male. Green eyelids. Blackened lips. A mouth held open to show teeth, teeth that never saw braces. “We won’t show them this kind of picture,” Mendoza says quietly. “We’ll show them first the pink comb he was carrying, and the label on his shirt.” Identified, the body is placed in a pine coffin nailed shut “so relatives remember him as he was.” Mexico City covers expenses for travel, and the family returns with the coffin to its village or town, in a truck or by bus or in a van, all together.

Hair, if available, is taken from remains that cannot be identified and stored in a repository at Baylor University for future DNA analysis, in hopes the deceased may someday have a name. “We can’t leave Mexicans dead, without care,” said Lopez. “If an American dies in Afghanistan the U.S. government is going to make sure they get back. We do the same thing with our own.”

Often it’s coyotes that lead lawmen to the dead. They call the sheriff or police. Once a coyote provided a map to the consul. Why coyotes? Before the mid-1980s, said Lopez, for migrants without documents “coyotes were not a ubiquitous factor, but now you need an organization.” Paths have become less direct, trickier, sometimes requiring alternatives, things smugglers would know. If a coyote arrives at a destination without his human delivery, however, relatives or whoever else paid for the trip (about $3,000 for Mexicans, up to $25,000 for Chinese) demand to know why. By communicating with the lawmen the body is likely to be found, which saves the coyote from reprisals.

When Falfurrias Justice of the Peace Loretta G. Cabrera answers the office phone and hears “Code 500,” she leaves for home, where a field set of boots, jeans, and raincoat are “always ready.” At the site she methodically notes the time and distance from the highway. Clothing. If the body is intact, paramedics and the Mexican Consulate are called. The funeral home field director helps collect remains if they are scattered. “Sometimes identification is not difficult,” says Cabrera. “When there are two ladies traveling together, one stays when the other dies; when an uncle dies a nephew stays; when one brother dies the other stays.” Sometimes, according to the consulate, phone numbers have been written on an arm, or even tattooed, either a premonition or as preparation for a journey whose risks are understood. The body goes to Corpus Christi, where the coroner performs an autopsy, and fills out a death certificate that invariably lists the cause of death as exposure. Then it goes to the funeral home. The mortuary charges the county a low flat fee, a little extra if the work requires a disaster bag (thick, black, with a firmly closing zipper, used when remains are not intact). “You walk out at the end of the day and don’t think about it,” said Cabrera, a small woman. “The Lord gives you strength. Someone has to do it.”

This routine of logging the dead repeated itself 56 times in Brooks County last year. (Only 20 persons died in the county apart from migrants, for a county total of 76.) In total, the Border Patrol recorded 453 border deaths including 187 in Texas and New Mexico. (New Mexico is included in the Border Patrol’s El Paso sector.) A General Accounting Office report last summer said recorded border deaths have doubled since 1995. It also said the Border Patrol initiative to collect data may be resulting in an undercount. No one knows, of course, how many die without leaving recoverable remains.

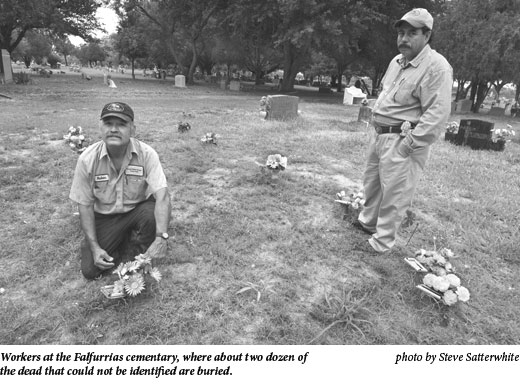

There is a small logistics problem emerging with regard to the unidentified dead in Falfurrias: Their section in the cemetery is running out of room. “We didn’t see this before,” says the mortuary’s field director, Angel Rangel, who has worked there 27 years. “Not a month goes by now we don’t find cadavers.” Once the funeral home kept just two disaster bags in stock; today it orders cases of six to 12 at a time. The mortuary is purchasing a 4-wheel drive truck because its van meant for paved streets is a ruin. “It might not sound like you want a loved one in the back of a truck but it’s the best way to take them out,” Rangel explains. He uses the term “loved one” for migrants, not “aliens,” “illegals,” or even, when they’re dead, “deceased.”

“Well, they’re someone’s loved ones,” he says. Like other locals, Rangel opines that as long as Mexicans need work and families want to be together, people will continue to risk the journey. “And the smugglers will keep telling them it’s not that hard. People have no idea they have to walk. We find housewives and the overweight. If you’re already sick, you won’t make it. The sand gives way as you walk so your feet start to burn. We find them with blisters all over their feet.”

Rangel seems affected by what he has seen, maybe because he makes the first call to the family for those who are easily identified. He wants me to know, however, that any relative who happens to be traveling with the dying person sticks around, even though it means both will fail at the enormous task they began. “They walk out there, father and son as a unit, a loved one slowly deteriorating. Here all those dreams just die, in the middle of nowhere.”

On an early spring morning, mist hangs among trees in the Sacred Heart Burial Park. About two dozen graves lie in a section by themselves, each topped with a small aluminum marker scratched with a pen knife. Names: “Unknown,” “Skeletal Remains,” “Remains, Male.” One says, “Unknown Female, d. Feb. 22, 2007.” They are graced with a motley collection of plastic flowers, some nearly overgrown by tufts of grass, others dusty, but adding color and linking the section somehow to the better-kept graves in the rest of the cemetery. Each aluminum marker names the ranch where remains were found: El Tule, Cage, King, Vickers, Laboretto Creek… A single bird sings in short bursts up in a tree somewhere, unseen. No one attended these burials. Where do all the plastic flowers come from? A caretaker passes. He shrugs. “Gente de buena voluntad,” he says, as if the answer were obvious. “People of good will.”

The Accidental Coyote

The seduction of easy money, $1,500 for a quick trip to Houston with an undocumented passenger, and no checkpoints to cross – has been too tempting for some residents of Falfurrias. “Bill,” 43, a heavy equipment operator with a wife and daughter, became a criminal two years ago, an accidental coyote. Someone offered him big money to take an illegal immigrant who had just made it through the desert for a no-risk ride – he’d start from north of the last Border Patrol checkpoint – and the extra cash became a habit. Recently he’s started working with a more serious, deliberate coyote, now running him down to Mission twice a week for $700 each time – again no risk, since Border Patrol isn’t likely to stop a car traveling south. There are probably fewer than a dozen such local coyotes, authorities and Bill say, and probably half of them would be doing something illegal anyway, running small amounts of dope, for instance. But Bill had never been in jail in his life, except for a few hours in high school for speeding. He’s not one of the despicable coyotes who lie and would just as soon leave someone to die when he’s squeezed off schedule. “I was trying to start a septic tank business. If I do it seven more months I think I can start.”

But the extra cash has helped Bill revive an old cocaine habit. And when a cop stopped him for an out-of-date tag and found an undocumented person in the car, Bill was warned and released but it went on his record, so he lost his good regular job and has settled for one that pays less. Starting the septic tank business may take more time than he thought.

He should quit or be extra careful; if he’s caught again he goes to jail. But now he’s a little afraid, just like some townspeople are cautious about local coyotes, lest they be connected to mean ones. “They should be afraid,” suggests Bill. Not of him, he insists, of others. “We each work with a chain and if you steal someone off another one’s chain or do something else they don’t like they say, ‘The mafia will take care of you.’ That’s the Mexican mafia.”

Bill doesn’t think he’d make it in prison. “I’m not the prison type,” he said.

Mary Jo McConahay is an independent journalist and contributing editor to New America Media.