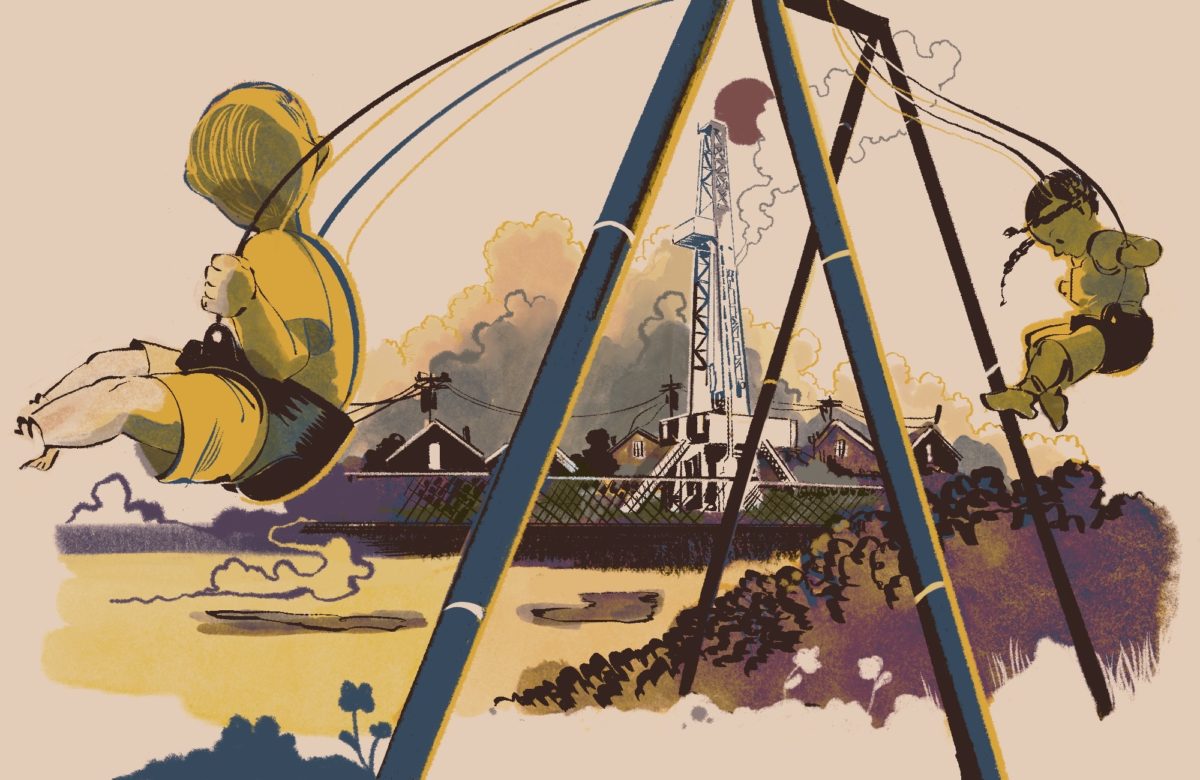

The Oil Boom Is Back, but at What Cost?

A version of this story ran in the April 2013 issue.

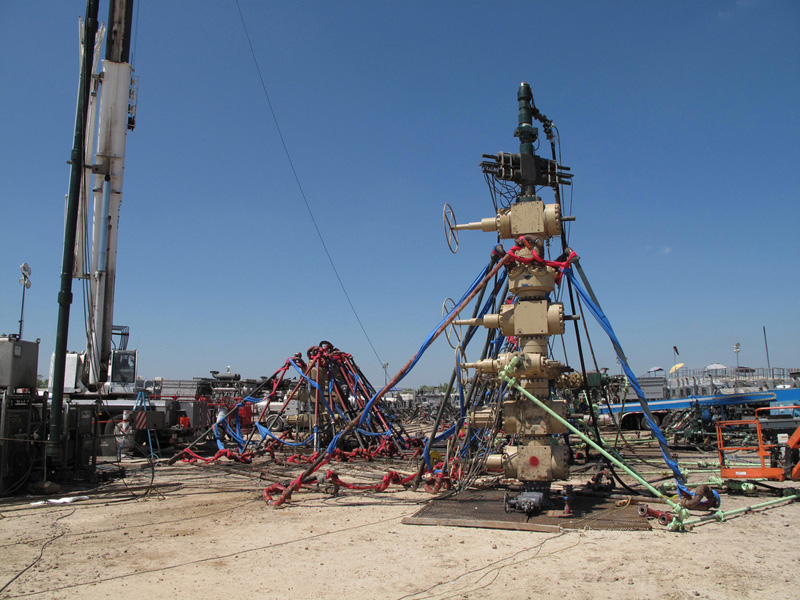

Above: Eagle Ford Shale

When I was a kid, the highest spot on our little South Texas ranch was the walkway at the top of our oil well’s tank battery. From there, you could take in a good piece of the gently rolling brush country. For a time, before it all came crashing down in the early 1980s, you could see the drilling rigs, the tank batteries, and the new oil-field roads carved through that patch of DeWitt County. Maybe you could spot men, like my dad, coming home from hard but good-paying jobs offshore or in the oil patch. The well on our ranch never produced much, and it was plugged once the boom turned to bust. And what a bust it was. In 1981, the oil and gas industry accounted for 18 percent of Texas’ economy and one-fifth of state tax revenue. When global oil prices tumbled, the Texas economy went into a deep depression, and workers went into other fields. At our place, the tank battery came down, leaving just a rusting “Christmas tree”—an assembly of valves and pipes—to mark the spot. Oil giveth and oil taketh away.

It seemed like that was the end of the Texas oil business. Of course, no one could’ve foreseen the fortunes awaiting in North Texas’ Barnett Shale, South Texas’ Eagle Ford Shale, East Texas’ Haynesville Shale, the Panhandle’s Granite Wash Shale and West Texas’ Cline Shale. No one foresaw that oil prices would climb to near-historic highs and stay there. No one foresaw that hydraulic fracturing (fracking) would be combined with horizontal drilling to open up gargantuan new domestic reserves.

The boom is back, probably bigger and longer-lasting than any before. The stats tell part of the story: In the past two years, Texas’ oil production has gone up 71 percent. Texas is now home to one-fifth of all drilling rigs worldwide. The Eagle Ford, which stretches 400 miles from Laredo northeast into East Texas, is attracting more capital investment than any other oil field on the planet. Just half a decade ago, the Eagle Ford was little more than a blotch on a geology map.

Last year, there were over 1,000 new wells sunk in the Eagle Ford and more than 352 million barrels of oil produced, far exceeding most analysts’ expectations. You don’t need to stand on top of a tank battery to see the night sky lit up with flares; in the rush to get oil out of the ground and to market, many producers are burning off any natural gas that comes up from their oil wells.

The Permian Basin’s Cline Shale could be bigger still. The Cline, which underlies 10 West Texas counties and is 10-times thicker than the Eagle Ford, could contain as much as 30 billion barrels of oil. Not that long ago, the game in the Permian Basin was tertiary recovery—squeezing the last drops out of dying fields.

Unthinkable as it once seemed, some experts now believe that the U.S. could surpass Saudi Arabia in oil production within eight years and become a net exporter. State Rep. Jim Keffer, the Republican chair of the House Energy Resources Committee, recently called it “a miracle.”

So much for peak oil. So much for the withering away of the carbon-based economy.

The vast energy and wealth generated by this oil renaissance is staggering. But at what cost? Can we afford to continue the carbon emissions that come with an oil-dependent economy? Oil money has a way of virtually silencing debate about climate change. It has a way of blinding us to the connection between Texas’ carbon emissions and its record-breaking heat and drought. It has a way of rendering mute the increasingly urgent warnings from climate scientists, including many in Texas. The planet has undergone just .8 degrees Celsius of warming so far and already the disruptions to the environment, from extreme weather events to a massive reduction in Arctic sea ice, have been greater than expected. Many scientists now believe it is virtually impossible for the planet to avoid 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 F) of warming, a threshold that the world’s governments have decided shouldn’t be crossed. Beyond that, things will get much worse, much faster. To avoid further catastrophe the impossible must be made possible: Texas, and other oil-rich places, will have to leave most of the carbon, the oil, in the ground. Oil markets go up and they go down, they boom and they bust. But we only get one chance to avert catastrophic climate change.