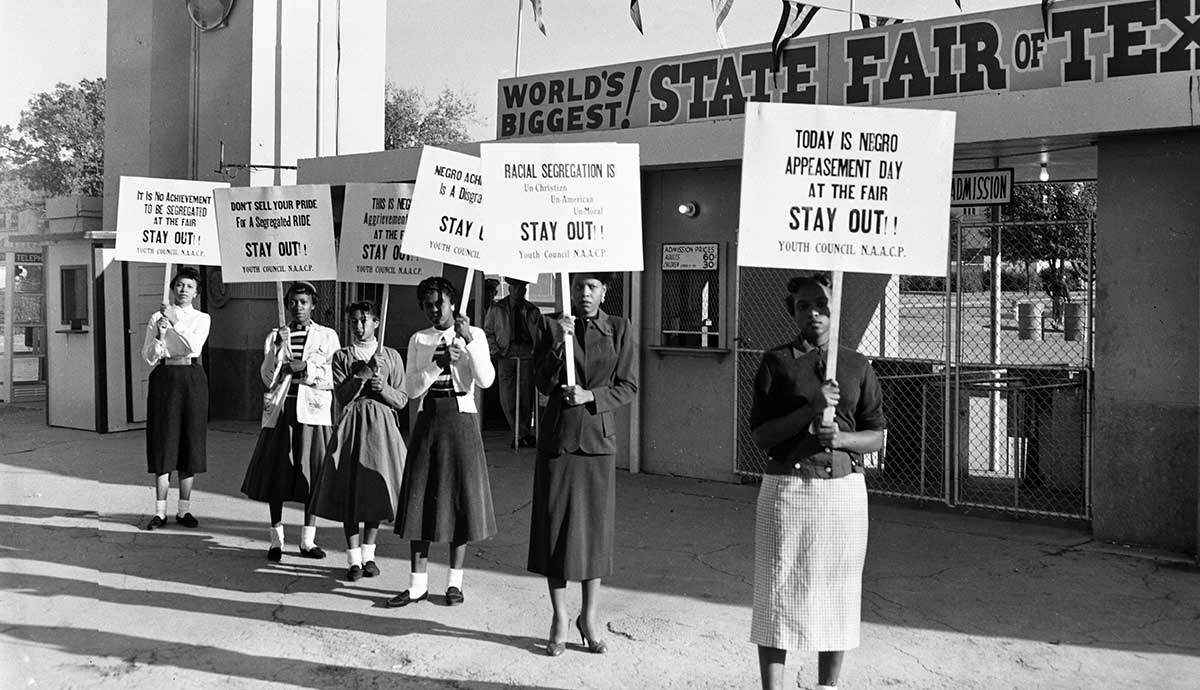

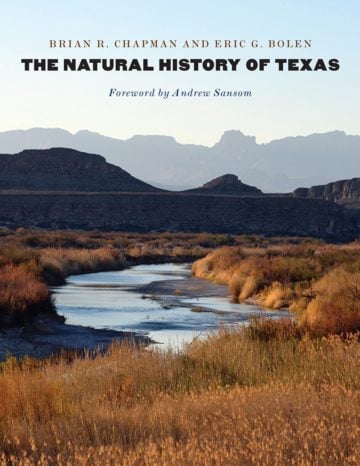

‘The Natural History of Texas’ Celebrates the State’s Lesser-Known Critters and In-Between Places

At first glance, the book appears to be a textbook. But it soon transforms into a welcome collection of oddities, a bestiary of the strange, unexpected and overlooked.

Above: Big Bend National Park in West Texas.

On December 7, 1941, two events coincided in a wholly unpredictable way. That the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor is household knowledge. Less well known is that a dentist — one Lytle Adams of Irwin, Pennsylvania — was driving home that night from watching clouds of Mexican free-tailed bats spiral out of Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico. In a fit of enraged patriotism, the good dentist hit upon a scheme: to strike back at the armies of the rising sun by using bats as bombs. President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the plan, after which events took on a certain inevitable speed. Bats were unwillingly recruited from Frio Cave, near New Braunfels, Texas, where generations before their mountains of droppings had been mined to produce gunpowder for the Confederate war effort. Now, it was decided, the bats would take a more direct role. After tying tiny time-released incendiary devices to the unhappy free-tails, the army set them loose over a mock Japanese village in Utah. Yet the bats’ desires for large roosting spaces hadn’t been properly accounted for: They ignored the enemy village and made instead for the cavernous, newly constructed buildings of a nearby military airfield, promptly burning it to the ground. The subsequent invention of the nuclear weapon gave everyone an excuse to put the whole strange affair behind them.

by Brian R. Chapman and Eric G. Bolen

Texas A&M University Press

$50; 390 pages

Such stories are scattered like diamonds throughout The Natural History of Texas, Brian Chapman and Eric Bolen’s sweeping account of the state’s ecology. Functionally, it’s a textbook, enlivened with serviceable photography. But the text itself is an ambitious interdisciplinary project, covering the confluence of rocks and water; temperature and elevation; and plants, animals and agriculture that give the state its many distinct habitats. Beginning with a discussion of what constitutes an ecozone (and a pocket history of how difficult reaching consensus on that subject has been), the authors then travel through each of the state’s 11 distinct regions, from the Piney Woods to the Trans-Pecos to the Gulf Coast.

Each region begins with a broad survey of soils, waterways and rock formations and their influence on plant communities, followed by an attempt to characterize the diversity of specific species found in an ecological zone. Here the problem of curation rears its head. Texas’ sheer size and diversity naturally make it a difficult subject, and the authors’ attempts to survey the vast breadth of the state occasionally blur into a litany of organism names. Following each overview are a series of deeper dives into specific animals and plants, sidebar discussions of agricultural or social history, and thumbnail biographies of naturalists who made strides in understanding the state. The end of every section devotes a bit of time to larger conservation concerns, which are by necessity somewhat repetitive: habitat loss, unsustainable agriculture, invasive species and hunting.

Defining an ecological boundary is, it turns out, about as artificial an exercise as defining a historical one.

These later portions of each chapter transform the book into a welcome collection of oddities, a bestiary of the strange, unexpected and overlooked. The authors strive to showcase more than just the usual charismatic big game: notable insects, fungi, reptiles and fish are all explored in detail. The cleanup efforts of the American burying beetle, one of the first insects placed on the endangered species list, are enthusiastically described; so are the seasonal (and mysterious) migrations of tarantulas and great mites, whose movements occasionally turn the prairies red. When more famous Texas creatures appear, it’s often with a welcome focus on their context within the environment and social history of the state. A lengthy description of bison herds on the rolling plains, for example, discusses the pulse of nutrients left by decaying carcasses, a natural way of enriching the soil now largely lost with the advent of industrial cattle farming.

But what makes the book particularly useful is its relentless focus on liminal spaces: the areas of Texas where geographies blend together. Defining an ecological boundary is, it turns out, about as artificial an exercise as defining a historical one. Communities of plants and animals have a way of meeting and melding, shifting back and forth across the landscape as resources and dumb luck permits. Exotic game ranches in the Hill Country have given the region wild breeding populations of Axis deer; prairies are increasingly swallowed by invading brush, including the omnipresent (and much despised) juniper. Changes inevitably ripple outward, sometimes farther away than anybody might expect. The expansion of rice farming on the coastal plains, for example, has led to a huge boost in the numbers of waterfowl, including snow geese, a Canadian species which often stops in during migrations. So rich is grazing in the flooded fields that snow geese flocks have grown massive, leading to them overgrazing the Canadian tundra when they finally return north.

Then there are strange relics of the past, seemingly out of place in the modern world. Texas holds scattered tracts of white sand dunes in the High Plains, the abandoned remains of barrier islands now stranded far from the ocean. Time leaves some organisms behind, too: the Osage orange, a fruit that once tempted mastodons and ground sloths, is now the sole remaining partner in an evolutionary dance. Human landscape engineering on a wide scale, the authors note, produces similar areas that are out of step with time: Ocelot and jaguar, now confined to slivers of Rio Grande brushland, once roamed as far northeast as the Big Thicket, while the scattered remnants of bison herds are locked away in preserves like Caprock Canyon. These sorts of losses have serious effects on the ecology of various habitats, the authors note.

But then again, everything does: That’s the point. By eschewing a grand narrative and piling on small stories, The Natural History of Texas exists primarily as a collage of connections. Millions of years ago, a warm sea lapped on the plains, fostering huge blooms of shelled organisms that settled in layers of limestone and chalk. Marine rocks fed rich blackland prairies filled with tangles of sunflower, Indiangrass and thistle. Tangled grass made for ample hunting country when people hunted buffalo and, later, cattle country when settlers brought cattle. Cattle and oil made the region wealthy; the wealth of the region fed great cities that swallowed up the prairie and exposed the white rock beneath. The past constantly acts on the present, and the future is uncertain. At some point, this shifting tapestry becomes history, a story of man acting on the land. It’s only natural to remember that there’s always more to the story.