The Late, Great Ogallala Aquifer

A closer look at the decline of the Panhandle's greatest resource

I’ve got a story coming out later this week on a Panhandle water fight. The story focuses on Hemphill County, an interesting corner of the state that’s taking a different approach to the Ogallala Aquifer. While much of the rest of the Panhandle has severely depleted the aquifer to irrigate crops or is plunging into water mining projects (think T. Boone Pickens), people in Hemphill are trying to leave their groundwater in the ground. It’s an effort to preserve the area’s unique prairie ecology and a traditional way of life.

Around Canadian, the “socially and politically conservative but civically progressive” seat of Hemphill County, the still-healthy water table feeds numerous springs, creeks and the Washita and Canadian rivers. There’s even a budding nature tourism industry in Canadian.

In reporting the story, I became interested in the fate of the Ogallala Aquifer, and more importantly the communities that depend on the aquifer economically and socially.

We know that the Ogallala hardly recharges and that it’s been drawn down significantly in many places. We can also safely assume that farmers and cities like Amarillo and Lubbock aren’t going to stop pumping anytime soon. Those facts mean that a Day of Reckoning will eventually come. But when?

Out of necessity, cities in the Panhandle and West Texas are coming to rely more and more on the Ogallala.

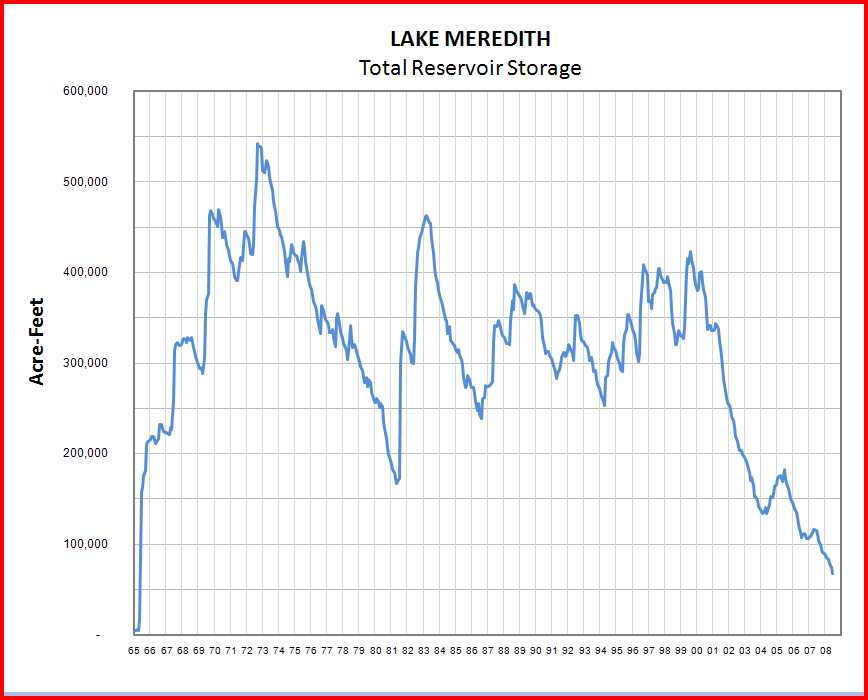

Lake Meredith, a drinking water reservoir near Amarillo that serves 11 cities, has been plummeting in volume for a decade and is rapidly approaching the “dead pool” level, at which point no more water can be withdrawn. Just today, the lake set a new record – less than 2 percent of its volume remains.

The Amarillo Globe-News had a story on Meredith’s decline today:

Meredith has been dropping most days for months and has shown a general decline for 10 years. Experts blame water-thirsty salt cedar trees, a falling water table that has dried up springs and a lack of hard rains to generate runoff in the lake’s watershed to the west.

With no end in sight, the Canadian River Municipal Water Authority and the city of Amarillo are scrambling to open up new well fields in Roberts County, a relatively untapped part of the Ogallala. Roberts County is also home to the majority of Pickens’ water holdings. If Meredith doesn’t bounce back, CRMWA estimates that it has enough groundwater to last over a hundred years.

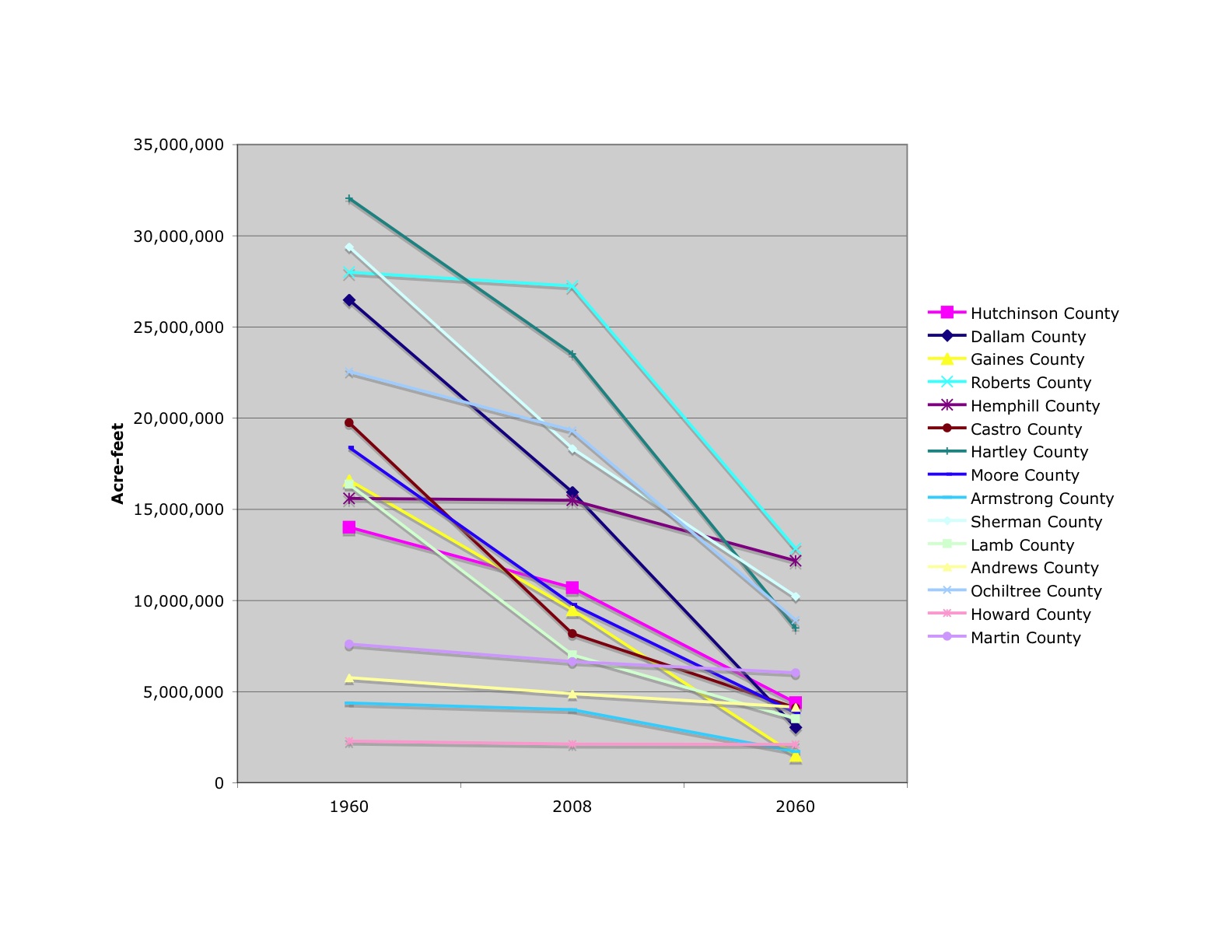

Meanwhile, water planners in intensively-irrigated counties are planning to drain 50-60% of the aquifer’s current volume by 2060. I had trouble understanding what that means so I got some data from the Texas Water Development Board. My Excel skills aren’t that great but here’s a chart I made illustrating aquifer levels in select counties for years 1960, 2006-2008 and projections for 2060. There are 47 counties that sit atop the Ogallala so I only included a handful that I hope are a representative sample.

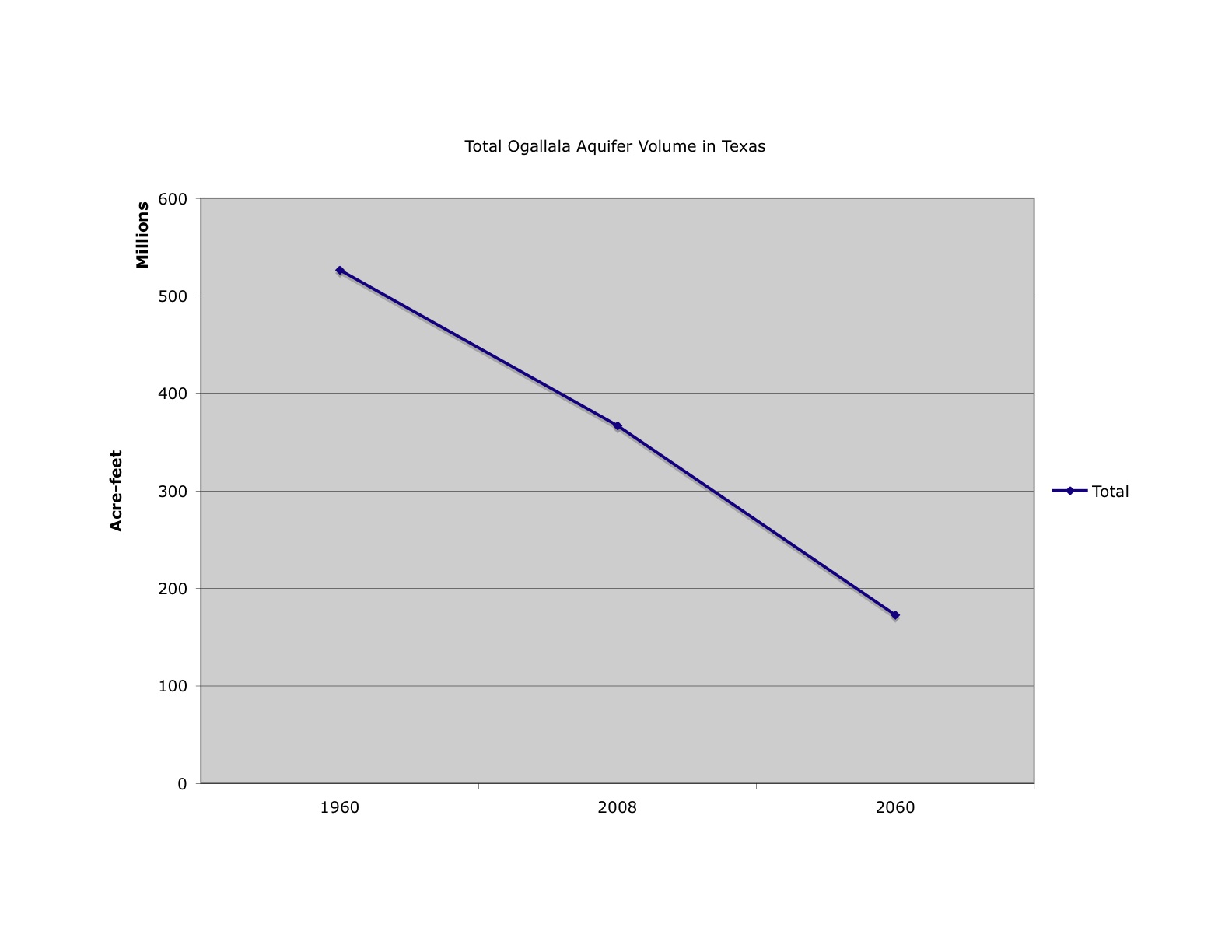

And here’s the grand total for the Ogallala in Texas.

As you can, the overall picture is one of severe decline. Unfortunately, there are no do-overs in the Ogallala. Once the water is pumped out and used, it’s gone for good. For decades, there were no limits on pumping. Indeed, it was widely believed that the Ogallala was a free-flowing subterranean river that could yield as much as man demanded.

It wasn’t until well into the 19th century that farmers realized that they were depleting their lifeblood and began to move towards some semblance of conservation. Still, the rate of decline hasn’t appreciably slowed.

I should also note that over the years a host of Cassandras has predicted the rapid, even apocalyptic, demise of irrigated farming. Nothing like that has come to pass – yet. More likely is a slow, halting decline in High Plains agriculture and the regional economy. Like so many other natural resources, the Ogallala is entering an Age of Scarcity in which rationing becomes a matter of economic survival. In concrete terms that means increased regulation and pumping limits. Case in point: Here’s a story (“Farmers face water limits”) from earlier this month in the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal:

But within a year, locally-elected water regulators said, the region will discuss limiting how much water irrigated agriculture worth billions of dollars may pump from the Ogallala Aquifer.

“Well-production limits are an option,” said Jim Conkwright, manager of the High Plains Underground Water Conservation District.

The move could mark the latest concession to keep conservation of a massive, waning resource meted out by local hands, which traces its roots back decades to the formation of the state’s first efforts by landowners to influence how the Ogallala Aquifer was preserved.

Wary grower groups and the landowners who will ultimately approve any rules looked to start the process in earnest some months after finishing this year’s harvest.

“We’re just concerned,” said David Gibson, executive director of the Texas Corn Producers Association. “We don’t want any large shocks to the economy, the landowners and the producers. I think even the water districts are concerned about that as well, to make sure it’s done in a manner that doesn’t negatively impact the area’s economy in a way that could be done differently.”

There are no engineering miracles that can solve the withering-away of the Ogallala. No amount of rainfall will replenish the aquifer, either. The choices that face everyone in that region are difficult. You can’t turn off the spigot and destroy an ag-based economy. Nor can you pump full-bore until the water is gone. So for now the region walks a middle path, gradually cutting back and preparing (hopefully) for the day when the well is dry.