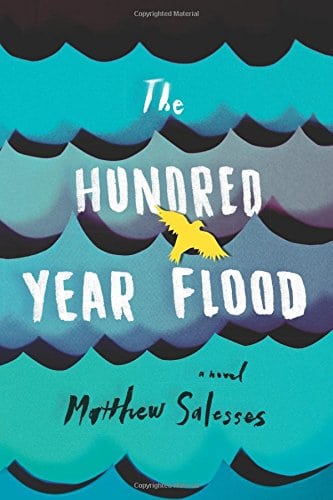

‘The Hundred Year Flood,’ A Search for Self in Prague

Houston author Matthew Salesses wrestles with identity in his newest novel.

A version of this story ran in the October 2015 issue.

By Matthew Salesses

LITTLE A

230 PAGES; $24.95 Little A

In August 2002, Prague suffered the worst flood in the city’s recorded history. The Vitava river burst its banks, flooding waste treatment plants and sending raw sewage and chemicals into the streets. Police moved from building to building, forcibly evacuating residents who couldn’t believe the water would ever reach them. It did. In the Karlin district, buildings collapsed as the flood reached the second floor. The most surreal images of all, however, came from the city zoo: a blindfolded rhinoceros airlifted to higher ground and tranquilized tigers lying one on top of the other, waiting their turns. One sea lion named Gaston became a kind of folk hero, escaping his aquarium and swimming all the way to Germany only to die, exhausted, a week after his bid for freedom.

Although that sea lion makes only the briefest of appearances in Matthew Salesses’ new novel, The Hundred Year Flood, set during the 2002 Prague disaster, the creature could be the spiritual double of the book’s young American protagonist, Tee. Adrift in the wake of a family crisis that leads to his uncle’s suicide and his parents’ separation, Tee heads to Prague, seemingly guided only by an inchoate yearning to jump the bounds of his own troubled identity: “Prague might be the perfect place, after all: a city that valued anonymity, the desire to be no one and someone at once.”

A Korean-American adoptee raised by white parents, Tee struggles with a sadness that predates his current problems. In an odd recurring metaphor, he envisions his inner life repeatedly as a “container,” filling up whenever he remembers details from his past or encounters problems in the present. The catastrophic flood, when it finally arrives, reflects his inner state, a torrent of undifferentiated emotions that threatens to drown him.

Over the past decade, Salesses has earned a reputation for writing movingly about race, identity and his adoption from Korea by white parents at the age of 2. In essays, short stories, flash fiction and a long-running column for the website The Good Men Project, Salesses has produced a semi-fictionalized record in real time of the pain that many interracial adoptees feel as adults, criticizing in particular the erasure of adoptee voices from parent-centric accounts. Speaking from that erasure, Salesses’ own voice hovers in the hinterlands between discourse and the unspeakable; his essays often read like thought fragments floating in a fog, and his novel in flash fiction, I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying, relied as much on the copious white spaces between blocks of text than on the vignettes themselves.

The Hundred Year Flood represents Salesses’ first attempt at a more traditional novel. In interviews, he has said he worked on it for a decade, and the plot — recent college graduate travels to a European capital in search of self, gets embroiled in old-world intrigue — is somewhat suggestive of a writer younger than Salesses.

By chance, Tee falls in with a famous Czech painter and revolutionary named Pavel Picasso, Picasso’s beautiful-but-melancholy wife and muse, Katka, and their thuggish friend, Rockefeller; a love triangle and other disasters follow, and the last one sends Tee back stateside to a head trauma recovery unit in a Boston hospital, where we find him at the book’s opening.

Structured by association and flashback rather than chronology, the novel often reads like a series of tenuously connected set pieces: Tee’s uncle flies his plane into the ground just a few days after 9/11; Pavel remembers his father, also a painter, being dragged away by state police; Tee sees a ghost, or possibly doesn’t. Random acts of violence seem motivated chiefly by the demands of the plot and are never otherwise explained. If at times this narrative porousness resonates with Salesses’ embrace of blank space over connective tissue, it also can be hard to distinguish from a failure of craft.

This minimalism extends to the sentence level, where Salesses tests the boundaries of metaphor with sparse, juxtapositional phrasing. When it works, the payoff can be lovely. For example, as the water rises outside the apartment where Katka and Tee consummate their affair, Katka hides a leg injury from him. The simple sentence “Her leg beat like a second heart” conveys an achingly physical throb, as well as the disturbing sense that Katka may cherish her secret pain almost as much as her secret love. Other metaphors, however, come off as distracting, even aggressive: “Katka woke with her leg in her mouth” suggests either a contortionist or a cannibal.

It’s hard not to wish that Salesses had found more direct means for Tee to confront the riddle of his origins.

The plausibility of such martyrdom aside, it’s hard not to wish that Salesses had found more direct means for Tee to confront the riddle of his origins. Early on, Tee bristles at being asked why he chose to visit Prague instead of Korea; coming from a stranger who sees only Tee’s skin, the question reveals ignorant and even racist assumptions. But a reader with a window on Tee’s pain might justifiably wonder the same. The easiest and most direct path to his identity, of course, lies with his parents in the United States. But Tee, like the refugee sea lion he spots from his rescue boat, seems far more intent on swimming away from his past than toward any particular future. And after all, what’s more American than that?