The state has already shown what can be accomplished when renewable energy is prioritized. Now, Texans want to take action. Do lawmakers?

*

by Amal Ahmed

September 19, 2019

An unexpected thing happened in 2005: Texas’ solidly Republican legislature passed Senate Bill 20, a renewable energy law that transformed Texas’ fledgling wind energy industry.

That year, a meager 4,000 megawatts of power had come from the wind, a miniscule portion of the state’s energy overall production, and an even smaller sliver of the total potential wind energy the state could have produced. SB 20 gave the state’s Public Utility Commission the authority to build 3,600 miles of transmission lines—infrastructure that would move power from windy, remote West Texas and the Panhandle (where wind resources are concentrated) to cities farther east (where power demand is higher).

It would also hopefully put to rest the perennial “chicken or egg” problem that hindered the industry at the time, says Carey King, the assistant director of University of Texas at Austin’s Energy Institute. “If transmission lines aren’t there, [companies] won’t commit money for wind turbines—and if the turbines aren’t there, how do you plan for more transmission lines and power plants on the grid?”

Before the transmission lines were built, around 17 percent of wind energy produced in the state never made it to the grid. After the transmission project was completed in 2013 (for a total cost of $7 billion), almost 97 percent of produced wind energy gets to the grid. And that’s even with increased wind energy production: From 2012 to 2013, wind generation increased by 13 percent.

Now, Texas gets nearly a fifth of its power from wind. Total generation in 2018 topped 75,000 megawatts of wind energy, far outpacing the state’s 1999 goal of achieving 10,000 megawatts of renewable power by 2025. And there’s more wind energy to be had. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, Texas has the potential to produce 1.3 million megawatts of electricity from wind, more than any other state in the country. Couple that with Texas’ small but growing solar industry—a dozen solar power plants are slated to go online within the next calendar year—and nuclear energy production, and the state already produces 30 percent of its energy from renewable sources.

That’s good news. A future in which Texas—and the rest of the world—gets all of its electricity from wind, solar, and other renewables will be necessary to combat the worst effects of climate change. (The world has about 11 years to go completely carbon-free in order to keep global warming under 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit—the commonly accepted benchmark to avoid the full intensity of wildfires, droughts, floods, and other environmental catastrophes.) It would also be required by law in a world in which a Green New Deal passes.

The bold but sometimes vague policy introduced by U.S. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey in February has been billed by climate activists as the United States’ last best hope at staving off catastrophic climate change. It would give the federal government leeway to spend billions, if not trillions, of dollars on transitioning the national economy away from fossil fuels and building up climate resilient infrastructure.

Transitioning a state synonymous with Spindletop and fracking to a 100-percent clean energy economy might seem like a moonshot, but it is possible. It will require scaling up the policies that have already been proven to work—like 2005’s historic SB 20. It will require investment in technology and commitment to implementing it. But mostly, it will require political compromise and will. And to some, that may seem like the longest shot of all.

*

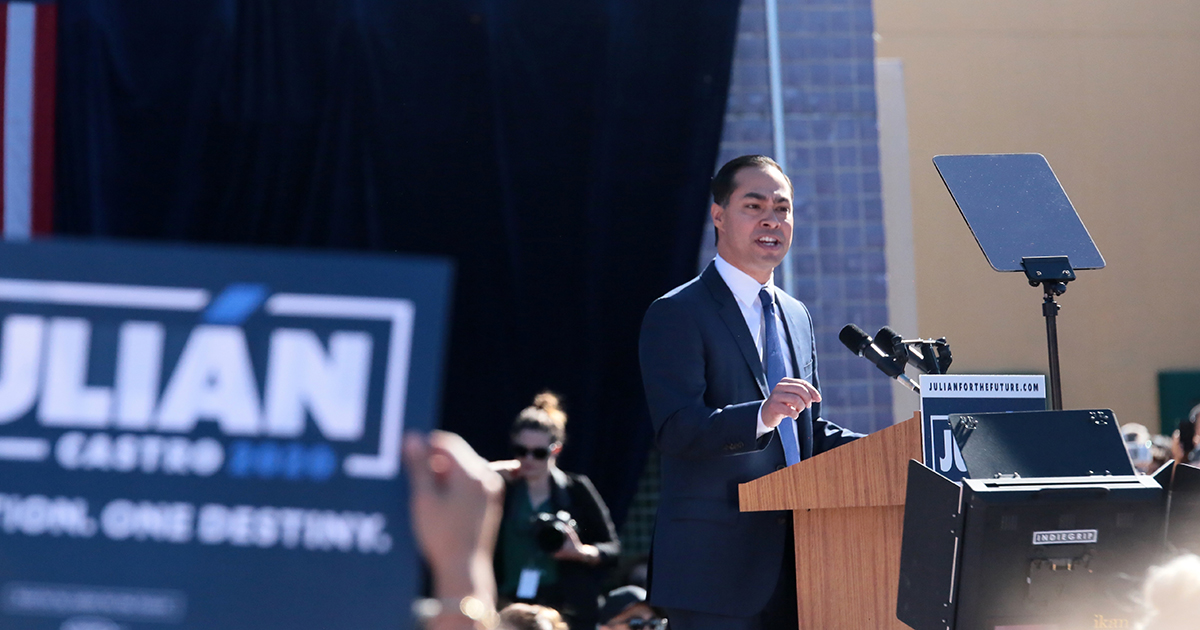

The Green New Deal has been widely embraced by many on the national stage, including Texas’ Democratic presidential candidates Julián Castro and Beto O’Rourke. Texas’ Republican politicians however, have predictably been skeptical of the plan. Back when SB 20 was passed, building transmission lines required using eminent domain to acquire land in scenic Hill Country, intervening in market forces, and raising consumer rates to pay for the initial construction—all practices that are anathema in much of Texas.

In past legislative sessions, comprehensive climate action bills rarely made it to the floor for a vote. But this year, lawmakers agreed to tap into the state’s rainy day fund to provide $1.7 billion toward flood control projects. And in a surprising move, it rejected a House bill that would have ended subsidies for renewable energy projects, despite lobbying from the Texas Public Policy Foundation, an influential conservative think tank.

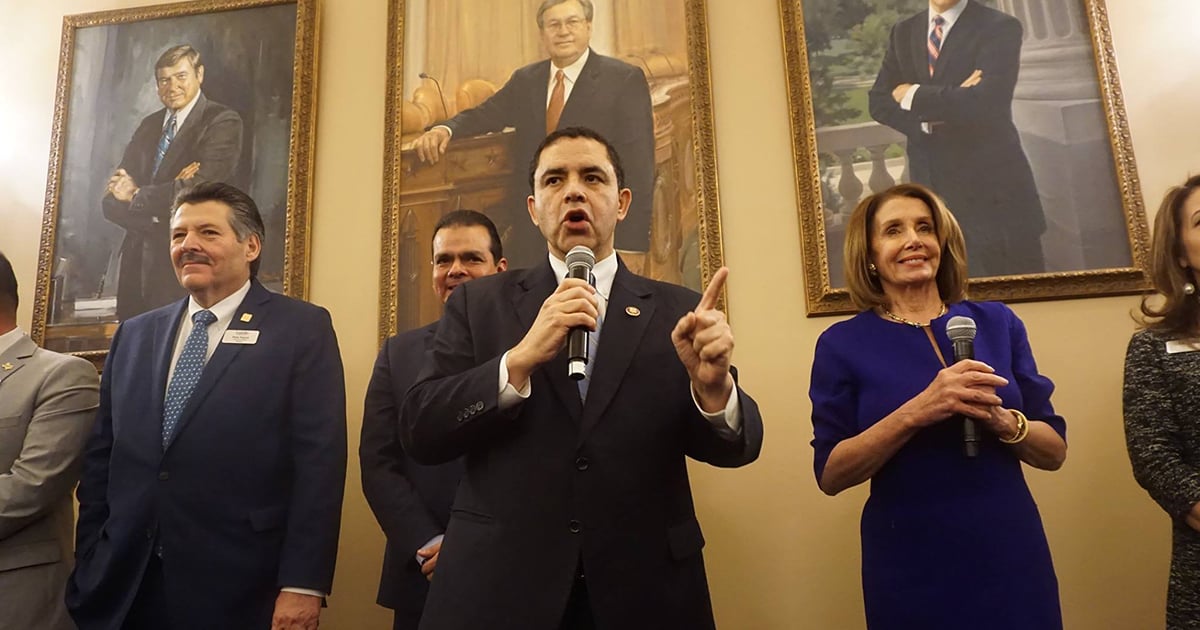

But criticism also comes from Texas Dems. House Representative Henry Cuellar, D-Laredo, who is facing a progressive challenger in 2020, tweeted that “The Green New Deal would kill jobs for hard-working Texans … Policies crafted by New York PACs won’t work for Texas.”

Cuellar’s district covers a swath of the Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas, where oil and gas operations have brought billions of dollars of investment, and created thousands of jobs. (Notably, Cuellar’s top industry donors are from the oil and gas sector, including companies like Valero Energy.) Even as oil prices have declined overall, drilling in the shale formation has remained relatively profitable. One company estimates that it could keep drilling in the region for at least 30 years.

Any serious attempt to curb greenhouse gas emissions in the near future requires that fossil fuel industries be relegated to the past. Thousands of workers would lose their jobs because those jobs simply wouldn’t be viable under a political framework that recognizes the very existence of the fossil fuel industry as a threat to the safety of millions around the world. In a state that produces three-quarters of the nation’s petrochemicals, that industry can’t be phased out overnight—or without a fight.

The promise of the Green New Deal is that government investments in infrastructure and industry would create new jobs with transferable skill sets, and job retraining programs would help transition workers from the fossil fuel industry towards cleaner industries. For example, King says, oil and gas workers with technical skills related to drilling in particular could apply that skill set to carbon sequestration—a growing field of research around capturing carbon from the atmosphere and pumping it back underground. Other projects might include ecological restoration in oil fields and drill sites.

“You can’t buy groceries with theories,” says Colin Strother, Cuellar’s campaign spokesperson, when reached for comment. “The Green New Deal is a fairytale—the idea that we are going to pass a $73 trillion bill that’s going to make every lawnmower, every freight train, every jet plane, and 97 percent of our cars obsolete is absurd. We need to be focused on practical solutions that we can accomplish.”

But in the most practical sense, continuing our current pace of fossil fuel consumption makes the reality of a hospitable, habitable earth a fairytale in the span of a decade.

*

As the Trump administration pulls the nation further and further from achieving climate and sustainability goals, cities have become key battlegrounds. In Texas, major cities like Austin, Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio have all come up with climate action plans, centered on the benchmarks set forth in the 2015 Paris Agreements. Flooding, droughts, and heat waves can cause massive economic losses. And the cities’ most vulnerable populations, like the elderly, the young, and the homeless, are most at risk from inaction.

San Antonio’s Climate Action and Adaptation Plan, which is up for a vote in City Council in mid-October, includes targets to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050—and a goal of reducing emissions by 41 percent in the next decade. While the plan has been criticized for its lack of specific policies, a chunk of the emissions reductions will come from switching the city’s energy sources to renewables, and investing in energy conservation and efficiency programs for new and existing buildings all over the city.

One of the city’s biggest challenges will be significantly improving its transportation systems. In San Antonio, the state’s second largest city, passenger cars and trucks account for a third of the area’s greenhouse gas emissions. Federal regulations on car efficiency standards have been rolled back in recent years, and there’s little that cities can do to force car makers to meet higher standards to reduce greenhouse emissions.

The city’s public transit system, VIA, accounts for less than half a percent of emissions. In 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, the system counted more than 100,000 bus boardings on an average weekday (that number includes riders who transfer). In a city as sprawling as San Antonio, it can be hard to incentivize public transit ridership, says Doug Melnick, the city’s chief sustainability officer. “VIA is stretched pretty thin,” he says, and needs newer, more frequent routes. The city is also aiming to incentivize higher density development, so that residents won’t need to commute as far between work, home, and other services. “If you have enough daily frequencies, and you’ve got on-time performance—you offer people an option, and people will take ownership,” says Allan Rutter, a research scientist at Texas A&M’s Transportation Institute.

This isn’t a challenge unique to San Antonio. Texas is notorious for its sprawling, car-centric cities and often inadequate public transportation systems. But improved public transit would also create climate equity. Texans who can’t afford to own a car often have to rely on infrequent, inconvenient, or unreasonably long bus and rail routes to get to work and school or to access amenities.

The options for long-distance, low-carbon forms of travel between Texas’ major cities are limited. The trip between Houston and San Antonio, the state’s two largest cities, takes three hours by car. But taking the Amtrak will set you back five hours—and there’s only one train making that route, three times a week. Pick any two cities in Texas, and a similar quandary exists. Even between Dallas and Fort Worth, a distance of about 30 miles, it’s sometimes more convenient to drive in rush hour than to wait for a train that will take the same amount of travel time. Rural residents of the state are even more limited when it comes to alternatives to hopping in a car.

The state hasn’t seen significant investment in public transit in decades. Amtrak, which is funded by both the federal and state government, operates most of its Texas routes at a loss. A high-speed rail line between Oklahoma City, Dallas, and cities as far south as Laredo has been under consideration since at least the 1980s. According to the Texas Department of Transportation’s project website, public support for the rail line justifies the costs, but securing the initial funding has been a major obstacle.

There’s some hope that a private company could start to change the status quo: Texas Central is hoping to break ground this year on a $20-billion high-speed bullet train between Houston and Dallas. Though the company has faced an uphill battle in receiving permits and acquiring rights of way through privately owned land, and limited support from the state, it could be fully operational within five to six years, finally giving commuters an alternative to flying or driving.

Though energy and transportation are the largest sectors of greenhouse gas emissions requiring transformation, the Green New Deal doesn’t stop there. It calls for supporting sustainable agricultural practices and uplifting rural, farming communities while sequestering more carbon in the soil. Homes will need to be retrofitted to consume less energy. Communities along flood zones that can’t be saved will need assistance in creating plans to retreat from coastlines and riverbanks. For other communities, better flood infrastructure and more accurate risk maps will be vital.

Following Hurricane Harvey, the governor and the legislature have said that they want to “future-proof” Texas from the storms that will continue to batter Texas. While references to climate are scarce in the report published by the Governor’s Commission to Rebuild Texas, it does propose solutions and climate mitigation tactics such as establishing regulations and codes so that new developments don’t increase flood risks farther downstream, or enhancing naturally occurring storm and flood protection, like wetlands, greenspace, and sand dunes.

*

The Green New Deal might seem like hard sell in Texas, but Texans increasingly support action on climate change. A public opinion poll from the Texas Tribune and the University of Texas found that 74 percent of the state’s registered voters said that the U.S. government should be doing something about climate change. Among younger voters, who will be left to face the consequences of inaction, that number is even higher.

Twenty-one percent of voters said the government should do nothing. But that comes with a steep cost of its own. Ocasio-Cortez’ bill puts the cost of inaction at $500 trillion annually. In the Gulf of Mexico, relative sea level rise is occurring at twice the global average. Coastal towns could vanish, as they already are in neighboring Louisiana, creating thousands of climate refugees. Stronger, slower-moving storms like Harvey were just a precursor to the destruction climate change will bring—when Hurricane Dorian hit the Bahamas this summer, it stalled over the islands for 40 hours. And although Senator Ted Cruz mocked former El Paso Congressman Beto O’Rourke for his fears of climate change in his landlocked hometown, further inland, Texans will experience longer droughts, more wildfires, and deadlier heatwaves.

Many Texans already know the costs. It’s why, on Friday, students in Austin will walk out of their classes and hold a rally at the State Capitol, demanding that elected officials take the necessary actions to address climate change. The strikes are part of a global movement of young people, inspired by the Swedish teen climate activist Greta Thunberg. Teens have heeded her call and planned strikes in almost every country on the map. And in Texas, there are events planned in the big cities but also in smaller ones like Midland, Nagodoches, Corpus Christi, and Amarillo.

“There’s a lot of work to be done in Texas,” says Matthew Kim, a high school junior at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School, who helped organize Friday’s strike in Austin. Kim is 16, but in his lifetime he’s already witnessed the effects of climate disasters in the state: the 2011 drought, which was one of the worst in the state’s history; Hurricane Harvey, and even now, Tropical Storm Imelda, which flooded streets and stranded hundreds of residents in Houston and Galveston earlier in the week, and ironically might rain out the strike planned in Austin. And time after time Kim and other young Texans have seen elected officials double down on the rhetoric of climate denialism. “We’re not just looking out for ourselves,” he says. “We’re looking out for the country and the world, because Texas has a lot to do with global CO2 emissions—we can take a stand and become a leader in stopping climate change.”

That’s what drove Kim and his peers to stage the strike on Friday, in the halls of power at the State Capitol. “Young people represent the voice of the future,” he tells the Observer. “And I’m not saying that as a cliche. It’s literal. These lawmakers can do what they want for the next few years, but when my generation enters politics, change is going to happen.”

This story is part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 220 news outlets to strengthen coverage of the climate story.

Correction: The original story misstated the name of Texas Central and the budget for the high-speed train, which is $20 billion. The story also erroneously converted 2 degrees Celsius as 35.6 degrees Fahrenheit. The Observer regrets the errors.

Read more from the Observer:

- Bridge to Nowhere: Near Brownsville, a trio of proposed liquefied natural gas plants endangers a fragile ecosystem and puts Texans’ health at risk.

- More Highways, More Problems: Highway expansion is the Lone Star State’s status-quo solution to easing traffic—but it actually leads to more congestion and displaced communities.

- Climate Change Will Make Harmful Algae Blooms in Texas Waterways More Common: Blue-green algae exists in almost all of the state’s waterways. Once it starts to bloom, it’s hard to get rid of it.