The Fight to Make Austin Affordable

Austin is one of the most segregated and sprawling cities in Texas. A new land development code aims to change that.

Above: Austin's revised land development code encourages the construction of “missing middle” housing—townhouses, duplexes, and accessory dwelling units.

On a brisk Saturday morning in November, a group of two dozen cyclists pauses in front of a four-story apartment complex in East Austin. The Terrace at Oak Springs, run by the nonprofit Integral Care, opened in September to provide housing for the formerly chronically homeless. But when the 50-unit facility was planned, “they had to create parking for each and every one of those units, despite the fact that only 10 percent of their clients have cars,” Greg Anderson, the cyclists’ group leader, explains to the others, who peer inside—most of the ground floor is parking. Devoting so much room to cars, he says, means less space and more money spent to house people.

“Our land development code cares deeply about automobile storage,” Anderson says. “You will never go homeless in the city of Austin—if you’re a car.”

Although this bike tour is intended to spotlight innovative affordable housing projects, traversing East Austin offers a study in unaffordability. Cyclers pass Fourth&, a three-story complex where a two-bedroom, 1,071-square-foot condo is selling for $485,000. Around the corner, a single-story home is advertised as a tear-down for $700,000—the dirt underneath the house worth more than the average Austinite will earn in a decade.

“When the vast majority of Austinites cannot afford a home, the form of housing must be allowed to change,” says Anderson, the director of community affairs for Austin Habitat for Humanity and a member of the city’s planning commission.

Anderson has been working to rewrite Austin’s land development code for the better part of eight years. The Saturday before the bike tour, Anderson sat through more than seven hours of public testimony as the planning commission considered changes to the latest draft, released by city staff on October 4. The 1,300-page document will dictate what can be built, where it can go, and how much parking it requires; it’s set for a preliminary city council vote on Monday, and requires three readings to pass. Meanwhile, Anderson is on a strike—he’s not cutting his hair “until we get a new land development code that allows for responsible land development,” he says.

“Our land development code cares deeply about automobile storage. You will never go homeless in the city of Austin—if you’re a car.”

Austin is one of the most sprawling cities in the state. Measured by population per square mile, it is less dense than Houston, Dallas-Fort Worth, or San Antonio. And it’s getting worse. According to an analysis by the New York Times, average neighborhood density in the Austin metropolitan area fell by 5 percent from 2010 to 2016, the second-highest decline in the nation (San Antonio was first). Because of all that sprawl, Austin leads the state’s major metro areas in the average number of miles driven daily, according to the Texas Department of Transportation.

“If you have a land development code based on exclusion, that’s the result,” says Jay Blazek Crossley, executive director of Farm and City, a nonprofit that advocates for sustainable development across the state.

The success of the revision to the land development code will determine whether or not Austin will accommodate its burgeoning population within city limits or continue to push people—particularly low- and middle-income earners—into the surrounding suburbs and exurbs, exacerbating environmentally destructive sprawl and deepening already entrenched segregation.

According to the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization’s transportation plan, the region’s population will more than double by 2040, adding more than 2 million people. The essential task of the land development code revision now before city council is to create the capacity for more housing—a lot more, and in every neighborhood. Increasing density would not only allow more people to live near their jobs and schools, it would also—in theory—increase affordability throughout the city, especially in neighborhoods that have long excluded low- and middle-income families.

“The long game is the idea that more units will help stabilize house prices throughout the region,” says Annick Beaudet, assistant director of Austin Transportation Department and a co-lead of the land development code revision team. With two new pro-housing council members on the dais, there is increased urgency to pass a new code.

“When we’re talking about displacement today, when we’re talking about gentrification, when we’re talking about the mass exodus of people of color of this city—it’s based on our code today,” says Awais Azhar, a Ph.D. student at the University of Texas at Austin and a member of the city’s planning commission. “We see this as an opportunity to address those issues head-on. How do we change so we don’t have to live with the legacy of our current code that we see around us today?”

*

The last time Austin updated its zoning code, Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Couldn’t Stand the Weather was the Austin Chronicle’s album of the year. It was 1984, and just under 400,000 people lived in the city, which covered 60 percent of the area it does today. When a new zoning ordinance went before city council on December 20, no one showed up to testify; it passed unanimously.

And then—you know this—Austin boomed. Nearly a million people live in the city now, with another million in the surrounding suburbs. Since 1984, Austin’s median household income has tripled to $60,200, but the average home price quadrupled to $381,500. Over the past decade, rent has increased by more than 50 percent citywide, leaving half of renters struggling to afford housing.

In 2012, Austin’s City Council adopted a comprehensive plan called Imagine Austin, a roadmap to build a “compact and connected city” that could “accommodate more people in a considered and sustainable fashion.” The following year, city council hired a California-based architecture and urban design firm to update the city’s zoning code, a process they dubbed CodeNEXT.

It did not go well. “Last round, the last person in the room or the loudest yeller just seemed to get their way,” Anderson says. “There wasn’t any cohesiveness.”

By August 2018, when Austin Mayor Steve Adler suggested that city council end the CodeNEXT process—which had “gone horribly wrong,” poisoned by “misinformation, hyperbole, fearmongering, and divisive rhetoric”—the city had spent more than $8 million dollars and six years on the effort with little to show but rancor and a whole lot of angry yard signs.

Adler passed the task of rewriting the city’s zoning code to Spencer Cronk, Austin’s new city manager. Cronk had moved to Austin from Minneapolis, which during his tenure as city coordinator approved a plan that permitted up to three homes on a single lot in all residential neighborhoods, effectively ending single-family zoning. Racial and economic justice was the first goal outlined in the Minneapolis 2040 plan, and city planners and advocates there were explicit about how single-family zoning had benefited white homeowners to the exclusion of everyone else.

In May, Cronk asked a newly elected Austin City Council to outline what they wanted the new code to accomplish. The council directed staff to create the capacity for an additional 405,000 units of housing in the city, mostly accomplished through upzoning parcels of land, or allowing for greater density (a duplex instead of a single-family house; a 30-unit apartment building instead of a 20-unit one). They also directed staff to create more deeply affordable housing: in 2017, the Austin Strategic Housing Blueprint (ASHB) had identified the need for least 60,000 units affordable to low-income households.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean all that housing will be built. “In Texas, we have very few tools to create income-restricted affordable housing,” says Erica Leak, the housing policy and planning manager for Austin’s Neighborhood Housing and Community Development Department.

Texas is one of only three states that prohibit cities from passing inclusionary zoning ordinances, which require developers to designate some units in new developments to rent at below-market rates. That means the city can only incentivize private developers to include affordable units by offering bonus entitlements—a taller building, say, or reduced parking requirements. (Parking is expensive to build, and thus, to rent: a new apartment building with no on-site parking is 20 percent more affordable than one with one spot per unit, according to the ASHB.)

The city already has a dozen such bonus programs in place, but they haven’t spurred much affordable construction, in part because many developers opt out—it’s simply too expensive to build affordable units under the current code. The proposed code revision would significantly expand the area available to the density bonus program, Leak says, from 5,600 acres to 30,600, and make the bonuses more attractive to developers by allowing for more market-rate housing to subsidize each affordable unit. If builders opted into all of the affordable housing incentives available in the new code—and that’s a big if—they would create an additional 9,000 units of income-restricted housing and 187,000 units of market-rate housing.

The revised code also encourages the construction of “missing middle” housing—townhouses, duplexes, and accessory dwelling units. This kind of housing is not inherently affordable—a new house still costs more than an old house—but two smaller houses are both more affordable than the giant ones currently being built throughout central Austin, Leak says.

The code concentrates upzoning for missing middle housing in residential areas lining “transition zones” along highly trafficked roads like North Burnet and South Lamar, in part to encourage the density that can support more public transit.

Of the many changes proposed by the code, it’s these transition zones that have stirred the most controversy. Homeowners turned out en masse to the planning commission hearing on October 26 to protest changes that they say will fundamentally alter their neighborhoods and run them out of their homes by increasing property values and pressure from developers to sell. (Zoning alone doesn’t change a property’s taxable value, Travis County Chief Appraiser Marya Crigler told city council—the market does.)

In a documentary about CodeNEXT released in September, Brentwood resident Barbara McArthur railed against the density coming to her neighborhood. The code changes are a “tool to turn over a city from one class of people to another,” she says.

In some ways, that is precisely the point. “Where people are located was and is the result of segregation,” says Kendra Garrett, an activist with the Austin Justice Coalition. “If you are going to challenge the racist legacies of this city, we have to redefine how we plan our communities.”

*

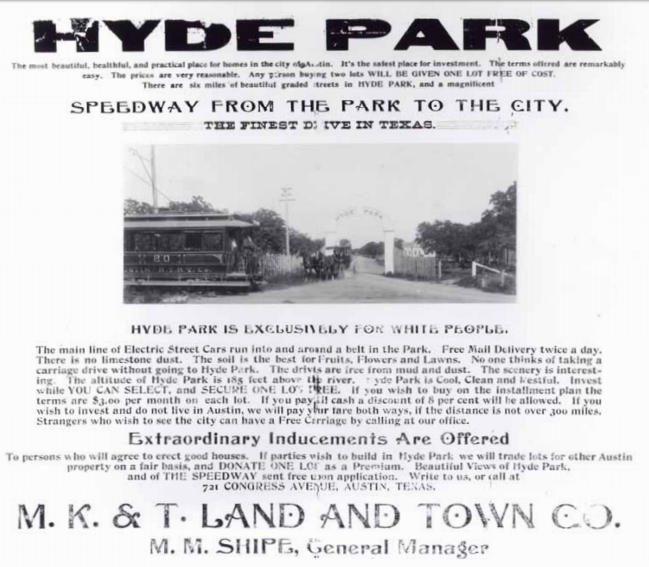

In Texas, like in the rest of the country, zoning began with the intent to segregate. When the Legislature gave cities the power to regulate land use in 1927, “it included a bill that provided for ‘the segregation or separation of the white and negro race and … the conferring power and authority upon cities to pass suitable ordinance controlling the same,’” writes Eliot Tretter in Austin, Restricted: Progressivism, Zoning, Private Racial Covenants, and the Making of a Segregated City. Although the law was ultimately deemed unconstitutional, it informed Austin’s 1928 comprehensive plan, which created a “Negro district” by restricting municipal services for black people to neighborhoods on the east side of the city.

Tretter documents the many ways that zoning was used to restrict where black and Hispanic people could live in Austin, cementing exclusions that began decades earlier in the form of deed restrictions that designed properties or entire neighborhoods as “exclusively for white people.” But less obvious racially motivated deed restrictions, such as house size or form, also limited access to neighborhoods and “may have been more significant in shaping the patterns of segregation found in the city today.”

Today, these restrictions appear in the form of minimum lot sizes, setback requirements (how close to the street a house can be), or compatibility standards (what can be built next to what). “They are all about figuring out how to maintain a kind of stability or uniformity in the housing and in the income level,” Tretter told me.

So, as Austin creates a plan for its future, is it confronting its racist past?

“No,” says city council member Natasha Harper-Madison. Then she hedges—“We’re getting there. We are healing from some deeply embedded wounds.”

On the sunny patio of the East Austin bar Nickel City, Harper-Madison reflects on how the neighborhood she grew up in has changed. “I remember the first time I saw a white lady running down 11th Street,” she says. “I remember when the Wells Fargo came. I was like, ‘Mom, they’ve got a bank on 11th Street!’” These were milestones, she says—not negative, simply noticeable.

In 2018, researchers at UT-Austin published a study that identified neighborhoods vulnerable to gentrification as housing costs rise. The map accompanying the report surprised no one—areas vulnerable to displacement were largely concentrated in an area that extends like a backward letter “C” across the eastern crescent of the city.

Although a new zoning code can do little to stop the wave of investment capital flooding East Austin and other neighborhoods, it can help redirect development. Community groups like Austin Justice Coalition and Planning Our Communities have urged city council to use the findings of the UT study to dial back the intensity of upzoning in those neighborhoods and instead increase it in West Austin.

“We know that generally in our city, West Austin has higher opportunity and has also historically been exclusionary, so we want to move away from those patterns and create an inclusive West Austin,” says Azhar, who in September helped launch Planning Our Communities, an advocacy group aimed at getting more people of color involved in development decisions in the city. The idea is to distribute housing capacity evenly across the city, so that every neighborhood bears “an equitable burden of growth,” Harper-Madison says.

The only black member of city council, Harper-Madison has taken heat for talking so explicitly about segregation and exclusion. A few weeks earlier, a women walked up to her inside City Hall and called her “an upitty nigger,” she recalls. Harper-Madison was so shocked, she laughed. But the nastiness tells her change is happening.

“Our city is changing,” she says. “We have to acknowledge and recognize that and then make the determination of, who do we want to be? And then, how do we get there?”