Thank You, Matt Rinaldi

Republicans who are repelled by people like Rinaldi have a problem: They depend on the votes of the people who cheer him on.

A version of this story ran in the August 2017 issue.

We spend a lot of time looking for what’s human and what’s kind in our politics, but it’s usually more important when someone shows us the opposite. To that end, Texans owe a great debt of gratitude to state Representative Matt Rinaldi of Irving, the lawmaker who punctuated a cruel and unhappy legislative session by calling ICE on immigration protesters, bragging about it to his Latino colleagues and then threatening to put a bullet in the brain of another lawmaker. Rinaldi’s allies tried to move swiftly past the incident, but it ought to be remembered as a moment when the GOP’s mask slipped.

Rinaldi is supposed to be one of the more intelligent members of the House Freedom Caucus, but his moment of angry catharsis will quite likely cost him his marginal seat. He also pissed off his fellow Republican lawmakers, who face the prospect of losing an unusually large number of seats next year. In that, he was doing what members of the House’s right wing do best: feed their id while screwing everyone else.

But Rinaldi did us a service. He punctured the partition that makes possible the respectability politics of the Republican Party. That’s the model wherein there are two groups: on one side, racists with cruel and condemnable beliefs; on the other, non-racists with opinions about border security, demographic balance and the integrity of the welfare system.

People in the latter category are often hideously offended when it is suggested that the division between the two is porous at best. When confronted, they will launch a uniquely American form of defense: “I’m not a racist,” or, the more biologically peculiar variant, “There’s not a racist bone in my body.” The idea is that intent is what matters. But what’s in our heart doesn’t matter at all. What matters is what we say and what we do, and what effect that has on others.

Earlier this session, state Representative Mark Keough offered a repugnant amendment to a child welfare bill that would have prevented undocumented residents from receiving state aid for taking care of young relatives who’ve been removed from abusive homes. Democrat Rafael Anchia took to the floor to say that the measure “feels like really racist, anti-Hispanic stuff.” Keough’s response: “I’m not a racist.” In its “Best and Worst” list, Texas Monthly reviewed the exchange and saw fit to chide… Anchia. The idea that a policy was racist was apparently too indecorous for polite company.

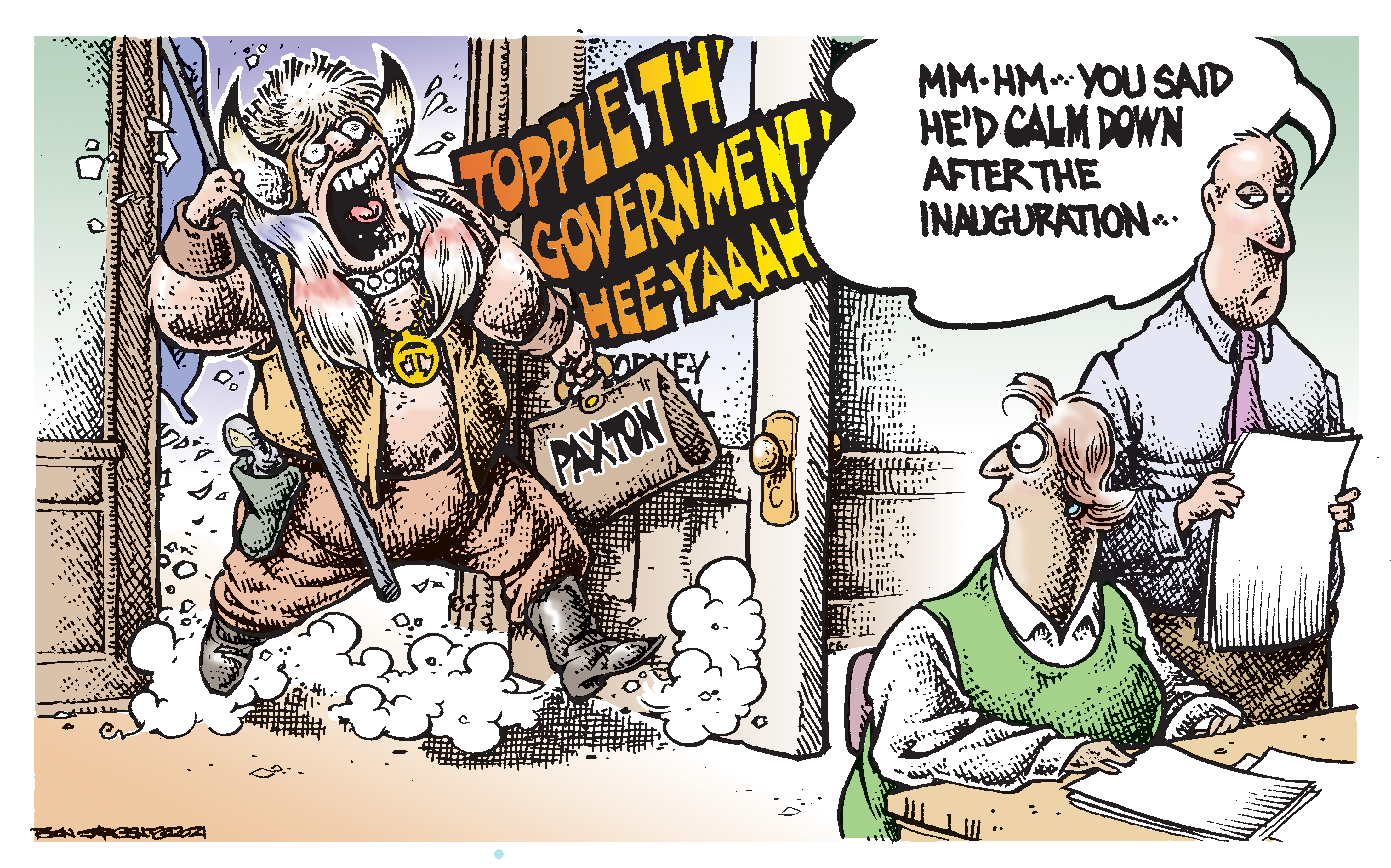

Rinaldi took all that posturing and blew it up. After initially riding hard for Senate Bill 4, the “sanctuary cities” bill, state leaders like Greg Abbott started to recoil from the backlash. They insisted that the pure-hearted measure was about public safety, not racial fears. And then Rinaldi saw some brown folks in the gallery and tried to get them deported.

Not every Republican is implicated to the same extent. Byron Cook took to the mic during the Keough debate to tell lawmakers that he felt “like crying” because of the cruelty on display. Then there are figures like former Land Commissioner Jerry Patterson, who loved to talk about Tejano soldiers in the Texas Revolution and called for a more realistic approach to illegal immigration.

But that’s part of the reason Patterson was destroyed in the Republican primary when he ran for lieutenant governor and the reason why Dan Patrick, who ran on the image of a white picket fence and a padlock, won. The racially fearful are their own interest group inside the party’s coalition. Republicans who are repelled by people like Rinaldi have a problem: They depend on the votes of the people who cheer him on.

The left has never had any illusion about this — maybe it’s easier to see from the outside — but a lot of smart Republicans have been in denial about the problem. Trump helped make things clearer. If you still doubt it, go to tea party meetings in Tarrant and Collin counties. Go to the rural town halls where constituents moan about Mexican women in the maternity wards of their local hospitals. Find the prominent Stormfront poster active in one of the most high-profile tea party groups, and watch her smile and pose with half of the state’s elected officials.

In Trump’s aftermath, you might hope that thoughtful members of the Republican Party would be grappling with the strangeness of their bedfellows. If they are, they’re doing it in private. Maybe they’re scared Rinaldi will shoot them.