Texas Prison System Sheds Men, Swallows Even More Women

Report says rise in incarcerated women hints at disparities in the male-dominated criminal justice system.

Above: Patsy Morin at the library in Mountain View Unit, a women’s prison in Gatesville.

More than 10,000 of the 12,500 women in Texas prisons have children waiting for them back home.

Not only are incarcerated women much more likely to be parents than men, most of them aren’t in prison for a violent offense, unlike male inmates. The majority of women in Texas prisons have also been abused by an intimate partner. More than half of them report having been sexually assaulted as children, many by the age of 10 or younger. A quarter of them say they traded sex for basic necessities like food and shelter before entering prison.

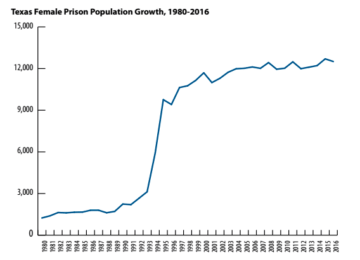

Those are some of the eye-opening findings of recent research into incarcerated women in Texas, the number of which continues to climb even as the state closes prisons and reduces its overall inmate population. While the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) reduced the men’s prison population by 8,500 between 2009 and 2016, the prison system grew by more than 500 women during that same period. Though men currently comprise 91 percent of the state prison population, the share of women is growing. Nationwide, women are the fastest-growing population behind bars.

What’s driving that paradox — a surge in the incarceration rate of women in the age of decarceration — isn’t entirely clear. Lindsey Linder, a policy attorney with the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, says bias, whether intended or not, in the male-dominated criminal justice system may play a role. To better understand the circumstances that lead women into the criminal justice system, Linder conducted detailed surveys from more than 400 women confined to TDCJ facilities for a new series of reports, the first of which her group published on International Women’s Day last week.

“What we see is a tremendous amount of victimization before these women enter the criminal justice system,” Linder told the Observer. “You have essentially a self-medicating population that’s largely ending up in the system as a result of the trauma they’ve already experienced.”

Linder says her report also shows how the movement to end mass incarceration may be disregarding the needs of women. “There’s an incredible lack of thinking intentionally about women in the criminal justice system,” Linder said. “I think that’s why the number has continued to rise even as reforms have impacted the overall population.”

Nationally, women now comprise a larger slice of the prison pie than ever before. Between 1980 and 2014, the country’s rate of growth of female imprisonment outpaced men by more than 50 percent. One 2016 report by the Sentencing Project blames the disparity on “more expansive law enforcement efforts, stiffer drug sentencing laws and post-conviction barriers to re-entry that uniquely affect women.”

“You have essentially a self-medicating population that’s largely ending up in the system as a result of the trauma they’ve already experienced.”

The disparity in growth extends to local jails, too. In Texas, the number of women in lockup awaiting trial has increased 48 percent since 2011, according to Linder’s report, compared to an 11 percent increase for men over that same period. That’s why counties across the state are planning for new space to jail more women, even as the number of women arrested in Texas has plummeted in recent years. Linder suspects an inability to pay cash bail or probation fees may be keeping women, who are paid less than men, in jail or cycling them back into lockup.

In Travis County, for instance, officials have pushed for a new $97 million women’s jail to house the rising number of female inmates. Travis County Sheriff Sally Hernandez insists her office desperately needs to replace the county’s deteriorating lockup with a safer and more therapeutic one. In a presentation to Travis County commissioners last week, county staffers called the new jail’s design “more college-oriented” and “more hospital-institutional than correctional complex.”

Travis County officials say they’ve implemented a laundry list of reforms to divert people from jail in recent years, such as drug courts and cite-and-release policies for certain low-level offenses. But the coalition of community activists, drug treatment providers and formerly incarcerated women who attended last week’s commission meeting questioned how well those programs are working, particularly for women. For instance, the number of women with mental health issues booked into the jail has doubled since 2013.

“What are our mental health diversion programs doing?” Cate Graziani, a researcher with Grassroots Leadership, told commissioners. “That is an indicator that they’re not working.”

Travis County commissioners ultimately voted 3-1 to delay funding the jail expansion for a year while officials search for ways to divert more women from lockup. Linder meanwhile is urging officials across the state to prioritize reforms that would help the kind of women she’s finding in the prison system — mothers with a significant history of trauma. More than half of the women who responded to her survey were diagnosed with a mental illness. About the same amount were poor and earned less than $10,000 a year before they were incarcerated. While TDCJ data shows 70 percent of female prisoners have a substance abuse disorder, compared to 58 percent of incarcerated men, half of the women in Linder’s survey said they never got treatment before prison.

Brandi French, who first entered prison at age 19, asked Travis County commissioners last week to put the money they would have spent building a new women’s jail into community recovery programs.

French, who calls herself a recovering drug addict, says she spent most of her 20s behind bars. She tried both college and church to stay sober, but neither worked. When she was 34, she went with her child to a place called Austin Recovery, one of only three treatment centers in Texas that allow women to bring their children with them. “It was the first time I was ever diagnosed with bipolar disorder,” French told commissioners. “First time, after seven years in prison. Nobody ever looked at my mental health issues.”

“Building a new prison is not the answer,” she said. “Putting sick people behind bars is not the answer.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correctly characterize Linder’s comments regarding bias in the criminal justice system.