Texas Lawmakers Are Singlehandedly Derailing Affordable Housing for Seniors

Unlike most states, Texas essentially gives state legislators veto power over affordable housing in their districts. Now that law is being used to derail low-income senior housing.

Above: State Representatives Lyle Larson (left) and Leighton Schubert

Long before Joan Hawn moved to Oak Bluff Village in Columbus, a Colorado River town about halfway between Houston and Austin, she knew it was the place for her when she got older. Now, at 72, she doesn’t know where else she could live.

Her apartment at the independent-living facility is adapted for the scooter that she needs as a result of childhood polio. And rents at other apartments in Columbus “are outrageous,” Hawn said.

But the almost 30-year-old complex is showing its own age. The door at the community center won’t open or close properly. The grass in the once-beautiful lawn is gone because of a broken sprinkler system. Problems with the plumbing and air conditioning systems are becoming more frequent.

In January, National Church Residences (NCR), the Ohio-based nonprofit that owns Oak Bluff and other homes for low-income seniors around the country, was preparing to apply for a grant through a federal program that uses tax credits to encourage development of affordable housing. The $2 million grant, which had enthusiastic support from city and county officials, would have paid for critical repairs and update accessibility at the complex, which houses “some of the most vulnerable and economically challenged … seniors in the community,” said Tracey Fine, a senior project leader for NCR.

The group had already filed a pre-application with the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs (TDHCA). “We had a very high likelihood of getting the award,” she said.

But that was before NCR ran afoul of state Representative Leighton Schubert.

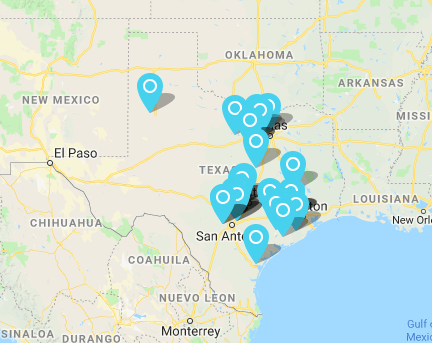

A 2001 state law gives individual legislators a virtual veto over low-income housing. It has essentially redlined entire legislative districts as off-limits to poor families, mostly black and brown folks, and drawn the scrutiny of federal courts and housing officials. And now that veto is also being applied to proposals for senior housing. In recent months, Republican legislators have derailed two NCR proposals in Texas. Oak Bluff was the first. The second was a new senior development in suburban San Antonio.

“I’m not sure what the impetus is behind this newly found fear of low-income elderly people.”

Under the 2001 law, members of the Texas House can award positive points to housing applications they support or negative points to those they oppose. They can even kill projects by doing nothing. Very few projects are approved without the active support of the area’s state representative — a major problem for state and local housing officials, who are under pressure from the courts, federal agencies and civil rights advocates to build low-income units in middle-class and affluent neighborhoods rather than just concentrating them in poor areas. But until recently, senior housing has faced much less opposition than family units. Compared to family housing, senior developments were so easy to get through the process that in some Texas cities, limits were placed on how many grants could go to projects for the elderly.

“I’m not sure what the impetus is behind this newly found fear of low-income elderly people,” said Charlie Duncan, research director for Texas Housers, an affordable housing nonprofit based in Austin. These days it’s even harder to pin down the reasons for opposition: In many cases, he said, developers realize that legislators hold all the cards, so they often “don’t submit full applications anymore” unless they can get support from legislators.

And when constituents object to a project, they often do so without showing up at a public meeting or writing a letter.

That’s the trouble that NCR encountered. As soon as NCR officials learned that Schubert wouldn’t support the Columbus proposal and that state Representative Lyle Larson was opposing the one in San Antonio, they put the brakes on.

Preparing a full application for tax-credit funding can cost $20,000 to $50,000. Without the letters, “It is not even worth submitting,” Fine said.

“I know that much of the opposition is happening behind closed doors and through verbal communication — not on the record,” Duncan said. “One of the bigger problems that seems to be brewing is that councils and commissions won’t allow a resolution of support to make it to their agendas, letting them die by the sands of time rather than taking an official position.”

If there was any opposition from Columbus residents to the funding for Oak Bluff Village, neither NCR nor city or county officials heard about it. Nonetheless, Schubert, who wasn’t running for re-election, declined to support the proposal to fix up the 39-unit complex. He didn’t actively oppose the subsidy; he didn’t have to. Simply remaining neutral doomed the project by denying the application the positive points that it needed.

Colorado County Judge Ty Prause said Schubert wouldn’t give a reason for his silence, but did insist that the project would get along fine without his involvement.

“I thought it would only take a phone call,” Prause said. “I did that. He flat told me that he had quit and the office was closed and he wouldn’t do anything.”

Oak Bluff, Prause said, is a tremendous asset to Columbus. “We are a small rural county, 22,600 people at last census. There aren’t any services” for the elderly such as an urban county might offer, he said. “It would just be tragic if it closed down due to this.”

Prause said the two Republican candidates vying for Schubert’s seat have both “given their assurance that they would support the grant” if Oak Bluff re-applies in the next round of funding.

In San Antonio, Larson did put his objections into writing. The legislator’s February 7 letter to TDHCA, which administers the tax-credit housing program, says that he had been contacted by several nearby homeowners concerned about traffic and “land use challenges.” He also pointed out that several hundred apartments are under construction in the area, “seeming to indicate that government support should not be needed for such a development.”

Fine said that not a single homeowner or homeowner group in San Antonio responded to NCR’s offers to discuss concerns, and the City Council had registered support for the project. And while there may be plenty of market-rate apartments going up in the affluent neighborhood, “there are no affordable units in this area and no senior units in the vicinity,” she said.

Larson didn’t return calls seeking comment for this story.

During the 2017 legislative session, various proposals to abolish or change the legislative point system failed to pass. Many other states, however, have reduced or removed the power of individual legislators to veto affordable housing developments, Fine said.

Texas is “increasingly isolated” in giving legislators so much power, Duncan said. He’s looked at the rules in about two-thirds of the states, he said, and none had the requirements for local political support that Texas does.

Many other states have reduced or removed the power of individual legislators to veto affordable housing developments.

In December, the National Council of State Housing Agencies issued a recommendation that housing agencies not allow local officeholders to veto tax-credit housing proposals. Another group, the Texas Affiliation of Affordable Housing Partners, noted that Texas has drawn criticism from both the IRS, which has a key role in the tax-credit housing process, and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, for, in effect, requiring local political approval of proposed developments.

Other states give points to projects that have “community buy-in,” but not to the point of allowing that to be a make-or-break requirement, said Michelle Norris, NCR’s executive vice president.

“I can tell you for a fact that Texas is pretty unique” on that score, she said.