Texas Has Room for More Charter Schools, But Few Applying

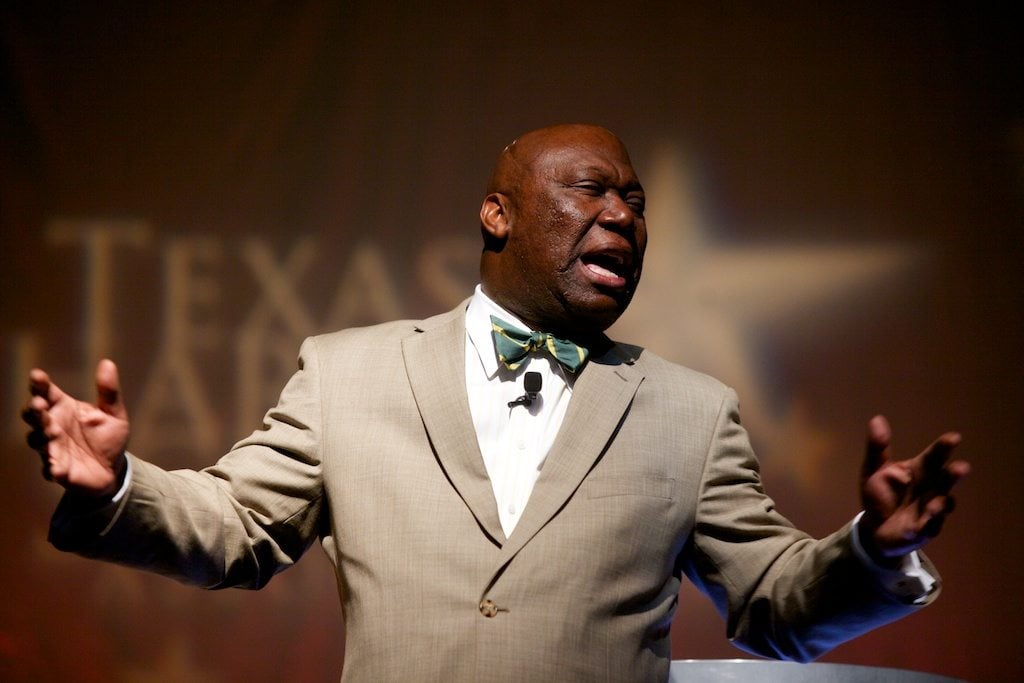

Above: Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams has kept charter schools on a tight leash.

Texas’ charter school system, which hasn’t grown too much since 2000, is suddenly poised for a massive expansion, after major reforms in the Legislature last year. All that’s missing now are the new schools—and don’t expect them any time soon.

The 100,000 families on charter school waiting lists made for a powerful talking point among lawmakers who wanted to lift the limit of 215 charter operators under state law. With the new law in place, that cap will rise to 225 this fall—in time for the next round of charter school approvals—and will keep growing each year till it reaches 305 schools in 2019.

But in this first year of charter expansion, with so much extra room provided by the new law, the state received just 27 applications for new charter schools—the lowest number since Texas began awarding charters in 1996.

“We’re struggling a little bit with why the number of applications dipped this year,” says David Dunn, who heads the Texas Charter School Association. One theory: Texas’ charter cap left so little room—about 10 open slots each year—the odds have just been too daunting for too long. With a little more room, he figures, Texas may not scare away so many would-be superintendents. “We think [raising the cap] is going to create much broader interest from folks out there,” Dunn says.

At the same time, though, the state is getting more selective with its charter approvals. Last year’s new charter school law took much of the authority to approve new charters away from the State Board of Education, and placed it with Education Commissioner Michael Williams and the Texas Education Agency. The result? An approval rate under 10 percent, the third-lowest ever.

In fact, some of this year’s 27 charter applications have already been rejected because the TEA decided they’re incomplete. (The agency won’t yet say how many, but in recent years it’s rejected around half the applications as incomplete.)

Here’s a look at total applications received and the approval rate over time:

If charter school advocates hope to cut into that 100,000-student waiting list, they’ll need to find a lot more schools with impressive applications.

“Back in the ’90s, the [State Board of Education] pretty much used the ‘thousand flowers blooming’ approach. There was not really enough vetting,” Dunn says. In 1999, the board approved 109 charter schools specifically geared toward at-risk students; today, 63 of them are closed. Last year’s law also made it easier for the state to shut down charter schools that don’t perform. In late 2013, Commissioner Williams recommended closing six schools that missed the new minimum standards.

As Dunn recently explained to the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, TCSA has three strategies for growing the charter school system: working with local community groups, helping out-of-state charter networks move in to Texas and building partnerships between charters and local school districts (a district might, for example, contract with a charter school to run its alternative campus).

Dunn says they’re only advising, not recruiting, would-be charters. But local groups like San Antonio’s “Choose to Succeed” have already bankrolled out-of-state charter chains like Arizona-based Great Hearts Academies’ expansion into Texas.

This year, just one charter school application came from an outside chain: California’s Rocketship Education, which made a failed bid last year to bring its computer-heavy model to San Antonio. The rest are locally grown.

With a wide-open invitation for so many new schools in the next few years, TCSA communications director Tracy Young says plenty more charter operators are looking to move in soon. Operators from other states see a few particular benefits in Texas—for one, while it’s hard to get your first campus approved, the state makes it fairly easy to expand to more campuses after that. Some charters run on grant funding that requires them to serve a minority population; Texas’ huge Hispanic population makes it a ripe market for them.

“Texas is viewed nationally as a good opportunity to grow,” Young says, because “the overall climate is supportive of charters, and generally supportive of school choice.”