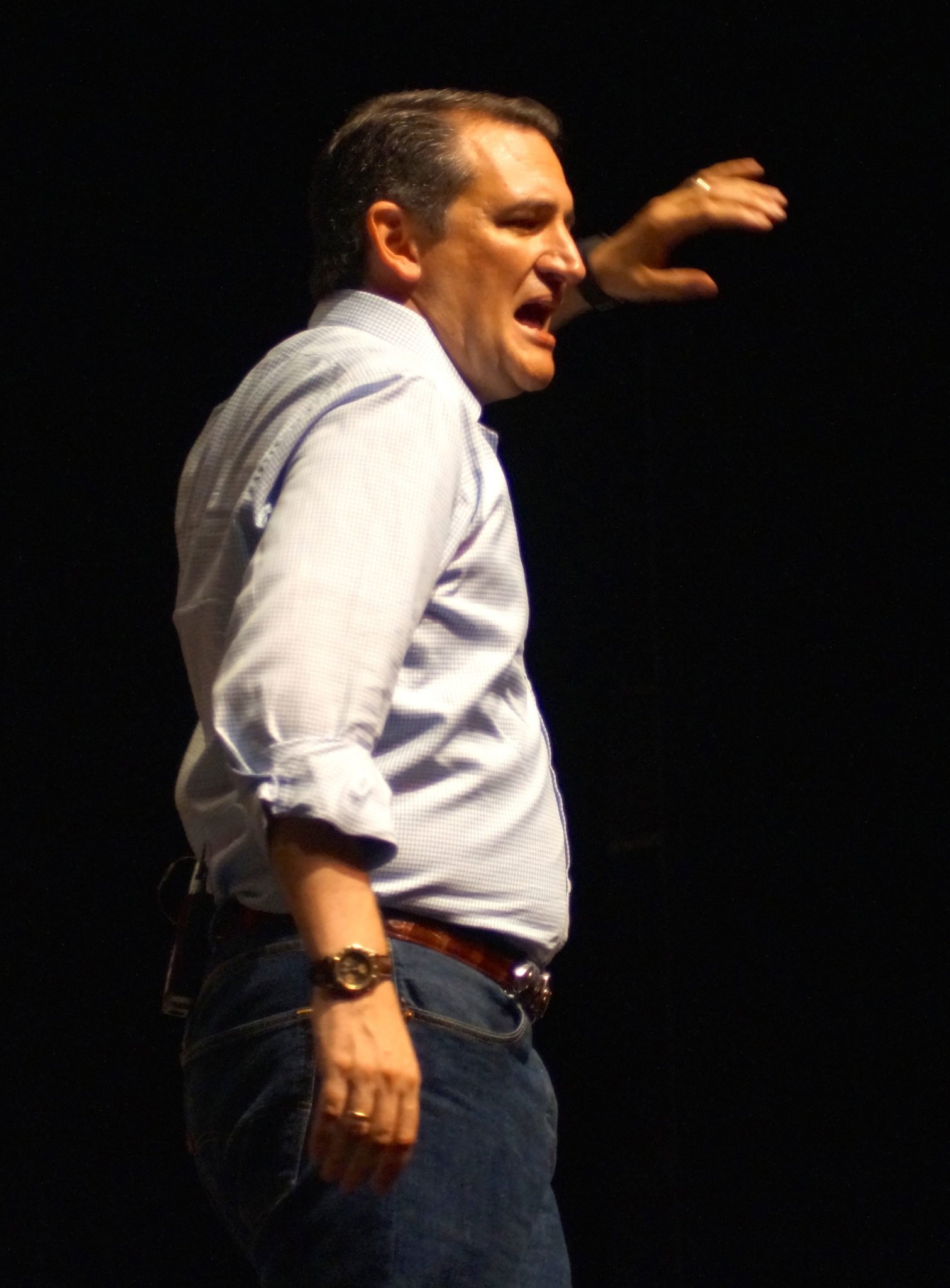

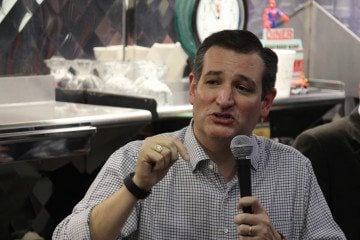

The Cruz-ification of the GOP

Ted Cruz's speeches haven't changed, but his audience sure has.

In Sioux City, Iowa, it took almost 100 minutes and 11 speakers for Texas Senator Ted Cruz to make his way to the stage at Western Iowa Tech Community College. Bob Vander Plaats, the evangelical ringleader, took the stage at 7:50 p.m. After him came Heidi Cruz, the senator’s wife, followed by, in order: Iowa Congressman Steve King; Jenny Beth Martin, the leader of the Tea Party Patriots, and no fewer than four of the group’s representatives, two from Texas; a son of Willie Robertson, Duck Dynasty’s Duck Commander, and then the Duck Commander himself, who led the crowd in a group duck call; and finally, Glenn Beck, who talked for a truly interminable period about early American history, at one point asking his son to bring him what he says was George Washington’s copy of Don Quixote, for reasons that I cannot adequately explain here.

Only then, at 9:30, did the introductory video for Cruz play. Music blared and a raucous standing ovation paved the way for the man who, for a few days at least, could credibly pose as the new leader of the Republican Party, which he had for years sought to undermine and manipulate. His future is uncertain, but Cruz’s win in Iowa was at least a partial validation of the years he’d spent in the trenches in Washington, D.C., accountable to no one except Texas primary voters and wealthy donors.

He’d come one hell of a way from the first time I saw him, at a Waco Tea Party meeting in the summer of 2011. Back then, his main primary opponent, Lieutenant Governor David Dewhurst, was still riding strong. In fact, Dewhurst skipped the forum. So Cruz showed up to beg for votes and give a speech that sounded remarkably similar to the ones he’s delivering now. But he wasn’t actually that distinguishable from the four other candidates, including a home caregiver who made a joke about being beaten by her husband, and an unemployed man who said God had told him to run.

His speeches might sound the same today, but a lot more people are listening.

He’s come a ways. So has Texas. Where once Cruz was a little-noticed frequenter of the Texas tea party circuit, he’s done more than any other Republican to set the tone in Congress during Obama’s second term. His acolytes and supporters hold the highest elected offices in Texas. Even if Cruz loses the nomination, he’s had an impact that will linger long after he does.

More than a dozen Texas elected officials went to Iowa to campaign for Cruz in the last few days of the race — former Governor Rick Perry, most notably, who used to say, or at least strongly imply, that Cruz was an ineffective, phony hack. But also Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and a crew of Texas senators, including Konni Burton and Brandon Creighton. Many of the state’s most notable tea party activists traveled to Iowa to volunteer for him, living in dorms for weeks and months at a time. They staged a little invasion. And they conquered.

Where once Cruz was a little-noticed frequenter of the Texas tea party circuit, he’s done more than any other Republican to set the tone in Congress during Obama’s second term.

There’s nothing unfair or untoward about that, necessarily. Cruz, and the people who followed him here, found a way to win. And politics is about winning. But they wouldn’t have this platform if Texas’ political culture were sounder, or more balanced. And what Cruz has done over the last four years is, of course, insignificant compared to the power he now seeks. Texas’ civic sickness has consequences. Our political culture has weakened antibodies, and we’re once again infecting the country.

Cruz faces steep odds going forward, and even if he does secure the nomination, he would be a terrible general election candidate. But the bitter and counterproductive fight between the two flawed candidates for the Democratic nomination should worry that party’s supporters. And if Cruz does get the true power he seeks, the blame begins first with us.