Still No Deal Between State and Feds on Disaster Food Aid for Harvey Victims [Updated]

A disaster food aid program deployed after Katrina and Sandy has yet to be approved in Texas.

Update, September 11: Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP) benefits will be available to Texans affected by Hurricane Harvey on Wednesday, according to a news release issued Monday by Governor Greg Abbott.

“In this time of need, this program will help Texans get back on their feet faster, as they will have one less thing to worry about,” Abbott wrote in the release. “The State of Texas will continue do everything it can to help Texans rebuild their lives as quickly as possible.”

The disaster food aid program, which is overseen by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC), will first be activated in an 11-county area that includes Dewitt, Gonzalez, Jasper, Karnes, Kleberg, Lavaca, Matagorda, Newton, Orange, Sabine and Tyler counties. Residents of those counties must apply in person between September 13 and 19 to receive benefits.

Houston and Corpus Christi, however, are not included in D-SNAP’s initial rollout because of the “large volumes of people who would not be able to be efficiently served through a local HHS office.” The program will be launched in those cities “in the coming days,” the news release said.

Original story:

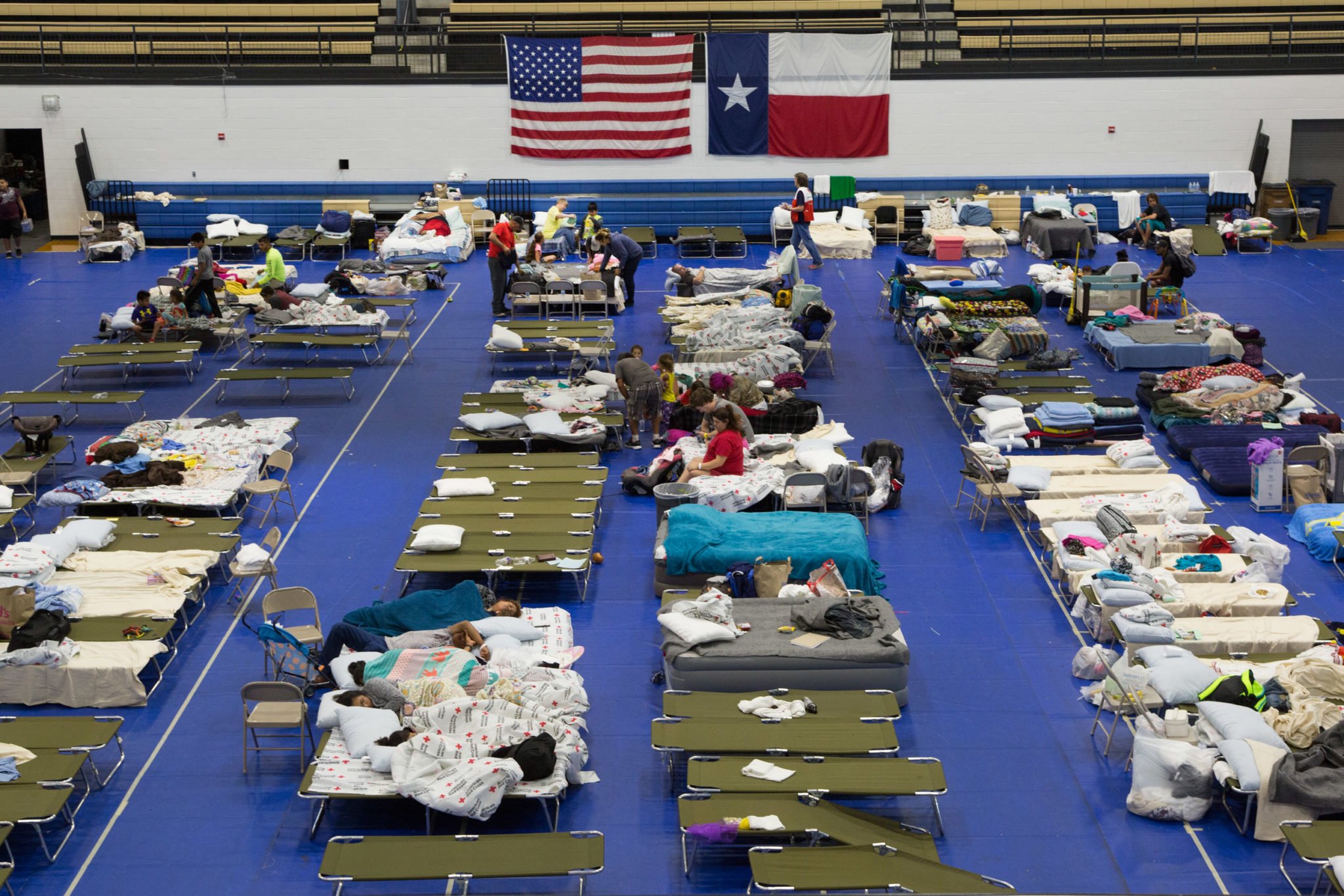

Some of Hurricane Harvey’s most vulnerable survivors could be benefiting from a food aid program specifically designed to help disaster victims, but inaction at the state and federal levels has kept help out of reach, experts say.

The Disaster Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (D-SNAP), a variant of the federal food stamp program, gives emergency SNAP benefits to victims of floods, wildfires, tornadoes and other disasters. Generally, the people who receive aid are not already enrolled in SNAP but are temporarily eligible for benefits because of property damage, unexpected medical expenses and other circumstances.

In the past, state and federal authorities have brokered deals to send big-time aid to people in disaster zones. Louisiana gave out $680 million in D-SNAP benefits after Hurricane Katrina, and New York and New Jersey distributed $43 million in benefits after Superstorm Sandy, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the agency that oversees the program.

“If you’ve lost your job, your house, that type of thing, you can apply for disaster SNAP,” said Rachel Cooper, a senior policy analyst at the Center for Public Policy Priorities. “It’s something the folks in these areas need really quickly.”

But Texans trying to rebuild their lives in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey can’t avail themselves of D-SNAP benefits until USDA and the state of Texas agree on how the program will be administered. The state’s Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) and USDA have begun negotiations on how to enact the program, but so far aid has not been approved. Cooper says the longer the talks go on without a deal, the more people will go hungry.

“It could be tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of people [who qualify for the program],” she said. “We’ve got damage from Corpus to Beaumont and people who are simply out of work.”

It’s unknown why Texas hasn’t launched the emergency program yet. In a news release, HHSC said the the state is “continuing discussions with the federal government about the possibility of a Disaster-SNAP waiver.” USDA Secretary Sonny Perdue wrote in a statement that “President Trump made it clear to his cabinet that helping people is the first priority, and that process and paperwork can wait until later.” But Perdue also offered this caveat: D-SNAP could be activated only “after commercial channels of food distribution have been restored and families are able to prepare food at home.”

D-SNAP approval has happened relatively quickly in the past. Ten days after eastern Louisiana was ravaged by prolonged flooding in 2016, state and federal authorities brokered a deal to activate the program, doling out $48.9 million in food assistance to 122,000 households. Authorities later agreed to extend the program, giving an additional $40 million in benefits. But sometimes the approval process lags, such as when New Jersey launched D-SNAP almost three weeks after Superstorm Sandy laid waste to the state in 2012.

Renee Treviño, an attorney at Texas RioGrande Legal Aid, said political ideology may be hindering negotiations to secure D-SNAP after Harvey. In his proposed budget for fiscal year 2018, Trump cuts more than $190 billion in federal spending from SNAP over 10 years. The budget also proposes levying a fee on retailers who accept food stamps, a move that drew concern from the grocery store industry and some members of Congress.

“It’s a matter of the willingness of Texas and the federal government to take action on a program where it’s their intention to cut, not augment,” Treviño said. “In general, we’re in a period of time where those in control would rather cut assistance to low-income people than provide basic food, nutrition and medical care.”

Last week, Texas and the feds announced an agreement to waive some SNAP rules, such as one prohibiting enrollees from using food stamps to buy prepared foods and another to expedite the transfer of benefits to enrollees’ SNAP debit cards. Still, the government’s food aid response won’t be comprehensive until D-SNAP is approved.

“The longer this is delayed, the longer the people with the most need are affected,” Treviño said.