Sick + Tired

Jefferson County is God and gator country. A 30-minute drive from the Louisiana border, past Spanish moss-draped cypress trees in muddy bayous, the county is a major cog in East Texas’ petrochemical corridor, a prime wealth generator for the state’s economy—but not for all its people. As you approach Beaumont from the west, you can’t miss the big billboard daring motorists to hold a baby gator at a roadside farm. You pass a gas station advertising Jesus Christ First Aid kits. On the radio, the exhortations of down-home evangelists compete with right-wing talk-show shouters testifying against health care reform. Socialism, they say. Nazism. Hitlerism. Americans and Texans beware.

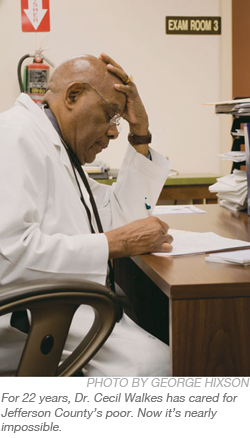

Every weekday morning, Dr. Cecil Walkes puts on his white coat, drives part of that route to work, and does what he was trained to do: save lives. For 22 years, his first stop has been the Jefferson County Indigent Health Care clinic in Beaumont. Still spry at 74, Walkes has run the county program, which serves the poorest of the poor, since its inception. Afernoons, he drives to the county’s other clinic, in Port Arthur, to attend to another crowded waiting room. Thousands of uninsured Jefferson residents have received preventive care from Walkes and his small staff of nurses. The crowds keep growing. The patients keep coming in sicker. Preventive care is becoming impossible. So is Walkes’ job.

On a Wednesday morning in mid-August, Walkes hunches over his desk in the downtown Beaumont clinic. He has a few minutes before changing into a tie and pinstriped suit to attend yet another meeting about how to contain the county’s spiraling health care costs. He spends a lot of time in a suit and tie these days. After the meeting, he’ll don the white coat again and head to Port Arthur. He’ll spend much of his afternoon working the phones, struggling to find physicians and hospitals willing to treat the serious illnesses that await him there.

When I ask Walkes what he thinks of the fiery debate over health care reform, he shakes his head and sighs. The mounds of paperwork that ring his desk look like they could collapse and engulf his slender frame. “I think we all need to take a deep breath and look at it in a rational way,” he says, measuring the words in his careful way. “One thing I do know is that the system is broken. We can’t sustain it much longer the way it is.”

As head of one of the state’s 154 indigent health programs, Walkes understands that better than most. In 1985, the Texas Legislature passed a bill requiring counties without a public hospital or hospital district to provide health care for uninsured residents who don’t qualify for federal and state programs like Medicare, which covers the elderly, or Medicaid, which covers some folks under age 64. The idea was to catch the poorest of the poor before they fell through the cracks. The trouble is that so many still do. Because of the state’s unusually stingy guidelines for Medicaid eligibility, fewer than 1 million of the approximately 6 million uninsured Texans qualify. Only pregnant women, the disabled, and children are eligible for Medicaid. County programs like Jefferson’s are supposed to pick up the slack. With local budgets strapped, the number of people without coverage rising steadily, and fewer hospitals and physicians willing to accept limited county reimbursements for charity care, the situation has become increasingly untenable.

The clinics are supposed to provide preventive care. By the time Walkes—a family physician by training—sees many patients, prevention is out of the question. In most cases, they’ve been diagnosed in one of Jefferson’s three hospital emergency rooms or bounced from one ER to another, then sent to Walkes. To qualify for the indigent program, patients’ household incomes must be 21 percent or less of the federal poverty level—no more than $4,630 per year for a family of four. If they meet that criterion, it’s up to Walkes and his small staffs in Port Arthur and Beaumont to find a hospital or physician who will treat them.

More and more patients qualify, and fewer and fewer places will take them. These days, Walkes spends much of his time trying to build a network of doctors and hospitals that will help his sickest patients. Because the region’s largest hospital, the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, has slashed the number of uninsured and charity patients it will take, that part of the job has swallowed up much of Walkes’ time, often to no avail.

More and more patients qualify, and fewer and fewer places will take them. These days, Walkes spends much of his time trying to build a network of doctors and hospitals that will help his sickest patients. Because the region’s largest hospital, the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, has slashed the number of uninsured and charity patients it will take, that part of the job has swallowed up much of Walkes’ time, often to no avail.

“I know of more than a half-dozen people who have died in the past two years because they had cancer or another serious illness and I couldn’t find anyone to treat them,” he says. “I have a diagnosis, but no one will treat them.”

He doesn’t like to talk about the patients who’ve died. “Please don’t make me go there,” he says, massaging his forehead and looking pained as the memories come back anyway. One in particular.

In October 2007, a 27-year-old man showed up at the Port Arthur clinic. The young man—because of federal health privacy laws, we’ll call him Sam—had been urinating blood. Sam was diagnosed with a kidney tumor at the local Christus St. Mary’s Hospital ER. Normally, Sam’s kidney would have been removed, and he likely would have survived. Because he didn’t have health insurance, Christus St. Mary’s referred him to UTMB. From there, his case became a classic illustration of how uninsured patients with serious and costly illnesses are bounced from ER to ER—triaged, as required by federal law, then sent on their way with life-threatening conditions.

Doctors at UTMB did some tests and sent Sam back to Port Arthur. He didn’t know where to turn. Several months passed. Sam’s tumor grew to the size of a grapefruit. Finally, at another local ER, he was told about the county’s indigent program. By the time he got to the Port Arthur clinic, the tumor took up half his abdomen.

Valerie McIntyre, a nurse at the Port Arthur clinic, picks up the story from there. She, Walkes and the other nurses struggled to get Sam enrolled as a charity patient at the University of Texas’ M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. It took them a month.

“We filled out hundreds of papers to get him in there,” McIntyre recalls. “And once they admitted him, they did everything they could to save him.”

As heartbreaking as such cases are, this one was worse. Along the way, McIntyre and her colleagues had discovered that Sam was the sole caretaker for his two mentally disabled brothers. Their parents had died of cancer. “He was such a sweet man,” she says. “He did everything for his brothers.”

At M.D. Anderson, Sam was given medications to shrink the tumor enough to operate and remove the kidney. By then, the cancer was too advanced. He died in June 2008, eight months after his diagnosis and shortly before his 28th birthday.

“There was a lot of time wasted between diagnosis and treatment,” Walkes says. “Here was a young man with a treatable condition. A young person who had all of this responsibility on him, and he didn’t get treatment in a timely fashion. Something like that shouldn’t have happened.”

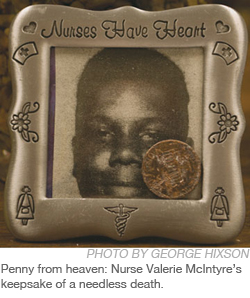

Increasingly it does happen. For Walkes and the nurses, it never gets any less traumatic. McIntyre keeps a poem she wrote for Sam on her desk, next to a grainy, black-and-white photo of him as a child that ran with his obituary notice. “I remember visiting him at M.D. Anderson,” she says. “He asked me whether he was going to live to see his birthday. He didn’t want them to put in the ventilator tube because he wouldn’t be able to talk to his brothers.”

She cried for four days after his funeral. “I was at the supermarket crying and I thought, ‘Lord, I really need to get it together.’ I looked down and saw a penny on the ground and thought to myself, ‘Pennies are from heaven. Maybe this was a sign from him.'” McIntyre points to the penny, now tucked into the silver frame that holds his photo. The frame is engraved with the words, “Nurses Have Heart.”

At least 47,000 people in Jefferson County—about 24 percent of the population, according to the latest U.S. census figures—are uninsured. In 2008, according to county auditor reports, 3,365 applied for help from the indigent care program run by Walkes. Only 1,535 were approved. Most were rejected because their household incomes were too high—more than $4,630, that is, for a family of four. The patients who were denied are among the growing number with nowhere to turn for treatment. Most will keep getting sicker. They’ll turn to a string of ERs for triage. If their illnesses become terminal, they will die.

Perhaps the most startling fact is that Jefferson County, with all these problems, actually has fewer uninsured residents than the state average. Texas has the highest percentage of people in the nation without health insurance—at least 5.9 million, about 26 percent of the population.

With the economic downturn affecting tax bases and strapping budgets, counties like Jefferson are hard-pressed to loosen their eligibility guidelines to serve more residents. Almost all of the Texas counties with indigent care programs—139 of 154—have set the limit where Jefferson’s is, 21 percent of the federal poverty level. It’s the minimum required by state law.

Last year, Jefferson County spent about $3.2 million on indigent care. That was about 5 percent of its budget. This year, with the same level of eligibility, the county will spend $4.2 million. Without meaningful health care reform, the demand and the costs will continue to grow.

“Everything is starting to tighten up, and the working poor are really putting pressure on the health system,” says Everette “Bo” Alfred, a Jefferson County commissioner who’s taken the lead on health care issues. “There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t deal with it in one way or another.”

The day before we spoke in August, Alfred had added an emergency agenda item hours before the commissioners’ regular meeting. One of the county’s residents had a growing tumor that had begun to block his breathing. Walkes’ program had already spent a month searching for a facility that would do the surgery, without any luck. After the county commissioners approved an extra expenditure to help the man, Walkes negotiated a one-time contract with UTMB to get the man admitted. Alfred said it was the first time in his seven years in office that the commissioners had to use an emergency line item to pay for someone’s surgery. It might not be the last.

The day before we spoke in August, Alfred had added an emergency agenda item hours before the commissioners’ regular meeting. One of the county’s residents had a growing tumor that had begun to block his breathing. Walkes’ program had already spent a month searching for a facility that would do the surgery, without any luck. After the county commissioners approved an extra expenditure to help the man, Walkes negotiated a one-time contract with UTMB to get the man admitted. Alfred said it was the first time in his seven years in office that the commissioners had to use an emergency line item to pay for someone’s surgery. It might not be the last.

Until last year, Jefferson, like 44 other counties in East and Southeast Texas, had a contract with UTMB to treat its indigent patients. Under the agreement, Jefferson agreed to foot the bill up to $30,000 per patient. After Hurricane Ike flooded Galveston Island last September, the hospital temporarily shuttered its emergency room and discontinued the contracts.

Walkes and his nurses felt the impact immediately. This year, he says, Jefferson’s clinics have seen a 45-percent increase in office visits. Walkes saw about 500 patients a month in 2008; he now sees about 800. In the past, many of those folks would have gone to UTMB.

Until this summer, county officials held out hope: With UTMB reopening many of its facilities on Galveston, perhaps the contracts would be renewed. But on June 25, UTMB administrators informed the counties that the terms of any future agreements would have to change. The counties would have to raise their eligibility requirements to 50 percent of the federal poverty level—more than doubling the limit—and do away with their $30,000 caps.

Dr. Ben Raimer, senior vice president of health policy and legislative affairs at UTMB, says the change reflects the medical branch’s return to its primary mission of training physicians. It’s also a matter of money. The hospital can’t sustain the costs of treating the growing number of uninsured and indigent patients in Southeast Texas, he says. In 2007, the last full year before Hurricane Ike, the hospital took a $1.1 million hit caring for 352 indigent patients from Jefferson County’s Indigent Health Care Program alone.”The patients we see have not had access to health care for years,” Raimer says. “By the time they reach us, they have a very complex disease state. Just to treat one person with cancer can cost anywhere from $60,000 to $100,000.”

In 2007, UTMB also treated an additional 2,460 uninsured patients from Jefferson County who didn’t come through Walkes’ indigent program, but were referred directly by hospitals or physicians. That cost UTMB much more: $8.1 million in uncompensated care. With UTMB no longer in the picture, Walkes and his fellow indigent-care administrators must search farther, and pay more, to find treatment for their patients. “At least before I was sending them somewhere,” Walkes says. “Now we have a situation where we are trying to develop a physician and hospital referral network. We’ve gone as far as Houston and Conroe to find physicians.”

With 44 other counties doing the same, competition is fierce. Costs keep escalating. Walkes, and his six nurses and caseworkers, spend hours every day trying to talk doctors and hospitals into treating their patients. Often they are turned away, Walkes says, by Houston facilities that are accepting folks from Montgomery or Galveston counties. The explanation: Jefferson, unlike the other counties, has its own hospitals, even if they’re not public. “The feeling is that we will be looked after by our own people,” Walkes says.

In the past, Jefferson County served as its own medical hub for the Texas-Louisiana border. But its hospitals, like others across Texas and the nation, are increasingly reluctant to serve the uninsured. “Most local hospitals, unless it’s an emergency, will find a reason not to admit a patient,” UTMB’s Raimer says. “In the past, they always sent them to us.”

Walkes has always had trouble getting local hospitals to take indigent patients. Jefferson County has three nonprofit facilities: two owned by the Christus Spohn network of Catholic hospitals, and Baptist Hospital, run by the Memorial Hermann network based in Houston. There’s also a for-profit hospital, the Medical Center of Southeast Texas, owned by Iasis Healthcare Corp.

“Oh, there have been all kinds of excuses,” Walkes says. “The general consensus is that if a provider or hospital takes too many of these patients, it will be known as an indigent practice or hospital. They are also afraid of the liability, because often the patients are much sicker by the time we see them.”

Katie Whitney, a spokesperson for Memorial Hermann Baptist Hospital, said that officials were not available to speak to the Observer, but wished the magazine “luck on the story.” Christus Spohn officials did not respond to interview requests. Nor did the president of the Jefferson County Medical Society.

“In my 22 years, I have never had a liability case against me,” Walkes says. “Their excuses don’t stand up.”

Commissioner Alfred is more forgiving. “I believe we should take care of our own people. But Beaumont also serves as a health care hub for several of our neighboring counties,” he says. “Some of those counties are the poorest in the state, if not the nation.” Alfred says he can understand why the hospitals don’t want to work with the counties. “They don’t want everything dumped on them,” he says. “They are businesspeople.”

Most of these counties’ commissioners also come from a business background. They realize that at some point the rising costs of health care could cause their counties to go broke. The crunch is not being exacerbated just by the growing numbers of indigent patients, either. It’s harder and harder to find doctors and hospitals that take Medicaid and Medicare patients as well. Jefferson County, along with m

ny others, has been forced to offer f

r more generous Medicare reimbursement rates. By August, Jefferson had already spent $386,000 more on Medicare reimbursements than it did in 2008. The biggest difficulty is finding specialists in such areas as neurosurgery, oral surgery, and ENT (ear, nose and throat). Recently Jefferson hired a service, for $30,000 a year, that does nothing but call doctors’ offices and hospitals seeking care for needy patients.

Despite the current debate over health care reform, public perceptions about the health care system are far too rosy, says Don Lee, executive director of the Texas Conference for Urban Counties, a nonprofit group that advocates for county governments at the Texas Legislature. Most people, Lee says, think the state takes care of its poor and uninsured—that there are always emergency rooms that “have” to treat sick people. That misconception, he says, has an impact on the debate.

“Medicaid and Medicare don’t cover a majority of the working poor,” Lee says. Indigent health care, he says, was “never designed” to be “a robust and rich program that covers all of the uninsured in Texas. It was designed to be a provider of last resort for people who had fallen through the cracks.”

The cracks have always been wide. It doesn’t help that Texas’ Medicaid program is downright miserly compared with most states’. To qualify, a family of three can earn no more than 12.8 percent of the federal poverty level. That’s $188 per month. More than two-thirds of uninsured Texans between ages 16 and 64 are employed and make more than that. They can’t qualify for the “last resort” of indigent care, either. Without substantial health care reform on the national level, the cracks in Texas’ porous system will continue to widen. Treatable conditions will go untreated. Local budgets will continue to drown as the state places most of the responsibility on counties.

Of all the things that rankle Dr. Walkes, nothing bothers him more than a simple fact: If the working poor had insurance in the first place, they wouldn’t be showing up sick in his clinics, desperate for help that he cannot give them.

On that Wednesday in mid-August, after his cost-containment meeting, I catch up with Walkes at the Port Arthur indigent care clinic. He invites me to join him as he examines a new patient, 42-year-old Roy Weldon. A year ago, he had health insurance through his job, stripping and waxing floors. Every two weeks he paid $72 to Blue Cross and Blue Shield. He was injured on the job and couldn’t keep working. His coverage was gone. Not long afterward, he found himself in a local emergency room with chest pains and numbness in his arms. He thought he was having a heart attack. Instead, it turned out to be two ruptured disks in his neck. He doesn’t know what caused them.

Weldon tells the doctor he’s been in terrible, continual pain for months. He hasn’t found anyone who will treat him. He’s been to the ER three times. He says he tried to go back to work stripping floors so he could become insured again, but the pain was unbearable. On his third ER trip, he says, he was referred to Walkes.

Walkes listens attentively, checks Weldon’s heart, and asks follow-up questions. Weldon’s fiancée, Tiffany Brown, watches and listens, propping her head wearily on the cane that Weldon uses to get around. “It’s been really tough,” she says. “He’s in constant pain, and I’m trying to be there for him while I go to school at the same time and take care of our daughter.”

Brown doesn’t have health insurance, either. Only the couple’s 11-year-old daughter qualifies for Medicaid. “We need change,” she says of the health care system. “We’ve got to come up with something better. He always paid his insurer on time, but once he got hurt, he was out of luck.”

After Weldon’s exam, we step back into Walkes’ office for a moment. Two patients are waiting in the other exam rooms. At least 10 more have assembled in the waiting room. It’s already close to 5 p.m. The clinic will stay open, as always, until everyone has been seen. The county recently agreed to hire a new nurse practitioner, at $65,000 a year, to help Walkes handle the increasing demand. It’s not enough.

The system will implode, the doctor predicts, if things don’t change soon. “We’ve already seen our financial system come down. I give our health system about five years before it collapses, too.”

As he observes the ongoing squabble over health care reform in Washington and listens to the popular rhetoric about “socialist medicine,” Walkes worries that genuine reform will never come. Part of the problem, he agrees with Don Lee of the urban counties group, is the myth that many Americans still cling to—that folks who must have care will get it somehow, somewhere. “If they were in the trenches and real observers in this so-called safety net, they would know it doesn’t exist,” he says. “If you don’t qualify for Medicaid or the county indigent program, you are in no-man’s land. If you can’t pay for your treatment, you are out of luck.”

Even at 74, Walkes still dreams of retiring and becoming a missionary in Africa. “If someone were to come along with a calling to do this kind of work, I would step aside in a moment,” he says. He smiles because he’s more than half joking. For 22 years, nobody has offered to take his place. The odds of its happening are not getting any better. After all, who wants to be the physician of last resort for a 27-year-old man who won’t make it to his next birthday?

On Sept. 8, Congress will reconvene to resume the intractable debate over reforming the nation’s sick health care system. Until a cure is found, Dr. Cecil Walkes will put on his white coat every morning, pick up the phone, and keep trying to save lives.