School Daze

Education funding is grossly inadequate and unfair. But can legislators fix a system that almost nobody understands?

It had the ingredients of a Tea Party rally—homemade signs, frustrated disaffection, thousands chanting slogans. But instead of messages lambasting government and the injustice of taxation, these protesters had a dramatically different message: “Texas: Open for Business, Closed for Schools,” read one sign. “Tax me,” read another, “Texas children are worth it.”

On the sunny second Saturday in March, 11,000 Texans massed on the state Capitol grounds to demand that the state adequately fund public schools. “Save our schools! Save our schools!” screamed the crowd throughout the day. Parents and teachers testified about their schools’ impending closures and the 100,000 education jobs in jeopardy. Speakers fretted about kids with decade-old textbooks or no texts at all; about needy students with no individual attention; and about gifted students with no challenging classes. “No child left behind will quickly become every child left behind!” shouted one second-year teacher whose job is on the block.

The takeaway couldn’t have been clearer: Don’t balance the state’s $27 billion budget deficit by making huge cuts in schools. In their initial budget proposals, the state House and Senate cut more than $9 billion from Texas’ already lean public schools. Gov. Rick Perry has said he only approves of using around $3 billion of the state’s Rainy Day Fund, which totals around $9 billion. With only half of that proposed to go to schools, the House budget still cuts around $8 billion. John Kuhn, superintendent of the Perrin-Whitt Consolidated Independent School District, captured the mood in an angry speech: “Do not be surprised when the men and women in this building fail to stand up for you, when they fail to stand up for the children you serve day after day!” he hollered. “Public schoolteachers, you are the saviors of our society and always have been!”

Most messages centered on the proposed budget cuts. But for three hours, as I scrunched and apologized my way through the dense crowd, I kept hearing hints that school funding troubles went far beyond the current crisis. Just hints. “Funding in Texas is broke,” Northside Superintendent John Folks told the crowd. “Funding in Texas is inequitable, and funding in Texas is inadequate.”

Allen Weeks, an organizer with Save Texas Schools, went into more detail about the big-picture problems. It started in 2006, he said, when “our legislators changed the way schools are funded.” My ears perked up. Now we’re getting somewhere. Now we’re going to get to the nut of the problem. Weeks could sense the rest of the crowd wasn’t as enthusiastic as I was for a lecture on school funding. “I’m not going to get into the details,” he said. “It didn’t work.” Then he led another chant: “Fix the funding! Fix the funding!”

Sure—but fix what? By the end of the rally, I had a sunburn and a lot of questions.

As eager as the protesters were to “fix the funding,” nobody seemed to know much about how education funding works. People knew they didn’t want local districts to face massive cuts. They knew they were mad at the governor, the legislators and, in some cases, with other voters. When I asked about the funding system, the parents and teachers didn’t have much to say. Fact is, almost nobody understands the system. School officials don’t. Legislators don’t. Parents and teachers can hardly be expected to master it.

Texas’ system for funding public schools is irrational and infamously hard to comprehend. It can stump the most dedicated policy wonk, much less a budding citizen activist. Ask Rebecca Pollard Pierik, an Austin parent who got involved in the rally when her daughter’s school district announced plans to close the school. “I’ve read everything I can get my hands on for the last couple months, and I still am surprised by the nuances that keep coming up,” she told me.

I knew how she felt. After two years of reporting on education in Texas, I couldn’t get a handle on the system, either. With Texas schools in jeopardy and their future likely to be defined by decisions made by this year’s Legislature, it’s become more important than ever to understand the roots of inequity and inadequate funding. Because education is the state’s biggest expenditure, budget cuts of some kind are inevitable. Those cuts will force legislators to come up with a new school-finance system, because the state can’t make significant cuts to school funding under its current system.

Long-term, systemic reform will have a far greater impact on Texas schools than the short-term issue of how many billions get cut. Few people are talking about the long term though. The reason is simple: Nobody knows what to say. It’s no secret that Texas’ education system is troubled through and through. The details are murky. That makes it harder for parents and teachers to fight effectively for more funding. If you don’t understand the system you’re trying to fix, you can’t advocate for the right fixes.

It hardly seems fair to ask regular working Texans to invest the hours and weeks necessary to figure out how Texas funds its schools—and why the system works so badly. So as school budget cuts loomed, I set out to learn the stuff and then explain it. It would be public service, I hoped. It would also be daunting.

In mid-February, at the first meeting of the Senate’s new subcommittee on Public Education Funding, the chair was frank about the challenges. As budget cuts loom, “Texas is going to have to look at education in a new paradigm,” said Sen. Florence Shapiro, a Plano Republican. That’s easier said than done, she added, because education finance is “a maze of rules, a maze of formulas that very few people, I’d venture to say, even understand.” She urged her committee members to work hard at understanding the committee plan so that “if nobody else in the building understands it, that the seven of us understand it.”

Good luck to them. You can’t understand how Texas funds its schools by looking at documents. If you’re like I am, you’ll get to terms like “guaranteed yield” or “target revenue” and start wondering if the phone book wouldn’t make more interesting reading. Instead, I picked the brains of the handful of lobbyists and legislators who’ve taken the dark journey into the tangled depths of our state’s education funding.

It turns out the basics aren’t so complicated. Overarching any discussion on school finance are two questions: How’s the money raised, and how is it distributed?

It’s like filling a bucket, I was told by one person after another. First, the state determines the size of the bucket—how much money a school district is eligible for. To fill the bucket, you start with the funds raised by local property taxes. If that doesn’t fill it, the state is supposed to fill the rest. If your bucket overflows because your property values are high, the excess is supposed to go toward filling up poorer districts’ buckets. (Dick Lavine, senior fiscal analyst at the Center for Public Policy Priorities, told me with evident pride that he once did an actual presentation with pitchers of water and overflowing glasses to demonstrate the system.)=

Most legislative sessions, the debate is over the size of the buckets different school districts get. But this year, the state doesn’t have the money to fill the buckets. Why?

“This isn’t a surprise,” another leading wonk said. “There were predictions this would happen when we implemented the new system in ‘06.”

If there was anything I heard more often than the bucket-of-water analogy, it was references to 2006, followed by a solemn assurance that you can’t understand what’s wrong with Texas school funding without understanding what happened then.

By the time the lawmakers gathered in April 2006 for a special session, everyone was exhausted, worn out and down to the wire. The Legislature had been trying to find new ways to fund education for years, and after the 2005 regular session, the governor had already called lawmakers back twice to search for a resolution. Local property taxes, which paid the bulk of education costs, were sky high, while the state was paying less than 40 percent of education costs. Constituents were complaining just as Gov. Rick Perry stood for re-election. Perry, facing three opponents in an unpredictable election year, had staked much of his political future on the issue. He had promised to pass school finance reform, but had come up empty.

In the winter of 2005, the Texas Supreme Court gave lawmakers a kick in the pants. A group of school districts had sued the state, arguing that because the state put so little money into education, local districts effectively had to charge the maximum allowable property tax rate to fund their schools. That amounted to a statewide property tax, they said, which the state constitution forbids. They argued there was so little money in the system that the state wasn’t providing “adequate” education—which the Constitution requires. The Supreme Court said that while the state was providing adequate education—barely—the fact that so many districts were charging the maximum tax rate did make for a statewide property tax. The state had until June 1, 2006, to fix the problem and give local districts meaningful discretion over their own tax rates. Otherwise, schools couldn’t open in the fall.

The governor had his opening. What had once been a school problem was now a tax problem. Before calling another special session, he appointed former Comptroller John Sharp, a Democrat, to head a new Texas Tax Reform Commission. The commission’s assignment was to find a way to reduce property taxes, and then find a way to make up for the lost revenue from those tax cuts.

The commission met Perry’s main objective. Sharp proposed a “tax swap”: Compress local property taxes by one-third, and replace the lost revenue with income from a new business tax and a hike in cigarette taxes. By the time Perry called a special session in April 2006, he’d garnered widespread support for the tax-swap plan among business groups and school districts. Most lawmakers were happy to support what sounded like an appealing compromise.

The math didn’t add up, though. The Legislative Budget Board, which tells the Legislature the financial impact of each bill, predicted the tax package would not make up for revenue lost to the property tax cut. The LBB estimated the measure would leave the state on average $5 billion short every year.

State Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn, who was challenging Perry for the governorship, called the bill a “hot check.” She argued that, within five years, the state would have a $23 billion budget deficit. “At worst,” wrote Strayhorn in a May 15 letter to the governor, the plan “will relegate Texans to Draconian cuts in critical areas like education and health care for at least a generation.”

The governor and his legislative allies shook off the criticism. Only eight state representatives voted against the measure. In the Senate, the plan passed unanimously.

I asked Sen. Robert Duncan, a Lubbock Republican, why he backed a bill based on fuzzy math. Duncan is known for taking his time to consider bills, and he’s long been immersed in education issues. He paused before answering. “I think we were all kind of wondering how it would work,” he told me. “We were all looking at both sides of it, and I came down on the notion of, I think it’s close enough and I think the economy, certainly at that time, was doing well. We thought quite frankly that it would balance out.”

The idea was that Texas was growing; so business taxes would surely grow as well. No one considered what would happen if property values went down.

“They were deluding themselves,” said Scott McCown, a former judge who presided over pivotal school-finance cases in the 1990s and now heads the progressive Center for Public Policy Priorities. He’s right. Five years later, the state has a $27 billion shortfall—due heavily to the imbalance. The bizarre measures adopted in 2006 have created vast inequalities among districts across the state—and vastly uneven educational opportunities.

Before 2006, the state gave money to school districts based on how much it would cost to educate students in the districts. Schools got extra money for students who were more expensive to educate, but they also got more money for other costs. For instance, small schools got extra money because, if your district only has 500 students, you can hardly take advantage of buying in bulk. The costs per student are higher. Logical enough, right? It was called funding by “formula.”

The problem in 2006 was that the formulas were out of date. The “cost of education index,” which was supposed to account for the costs of teacher salaries and other expenses, was based on data from 1989. Districts that had been rural in the ’80s were still funded that way—even if they’d become booming suburbs. The formulas didn’t offer enough money to districts. But at least the distribution of funds was based on the cost of educating students. Formula funding, which the state had used for decades, was imperfect. It made sense, though.

Sense went out the window in 2006. Updating the formulas would take time—and huge amounts of money—and it would raise all sorts of political fights between members. Rather than go for a systemic solution, the Legislature opted for what they said would be a temporary quick fix. They would add money and freeze district funding at a certain amount per average daily number of students. (They weighted the counts for expensive-to-educate students, like those who are bilingual or special needs.) Most education advocates supported reform because it offered them more state funding. There was even a modest pay raise for teachers. Districts were too desperate to sweat the long-term implications. “They hadn’t gotten any new money in a long time,” said Rep. Scott Hochberg, a Houston Democrat and the Legislature’s leading school-policy wonk. “If you’re on the side of the road and you don’t have any gas and someone comes along with half a gallon, you take it, and you go on down the road as far as you can even if it doesn’t get you to where you’re going.”

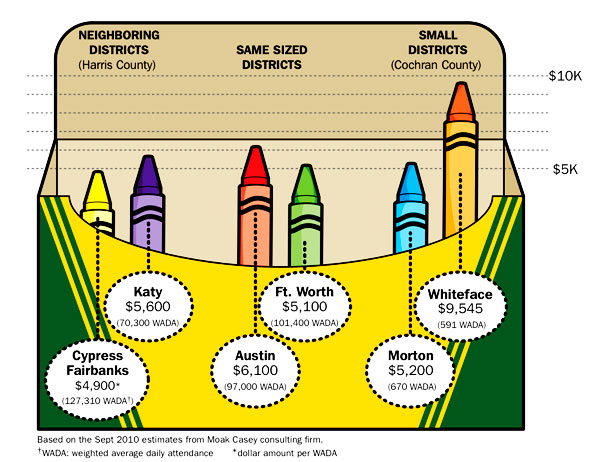

The new funding amounts, frozen at 2006 levels, quickly became irrelevant to actual costs. The amounts—now called “target revenue”—were based partially on how much a school district received in formula funding in previous years, but they also took into account how much a district could raise in its own tax base. That heavily advantaged wealthy districts. The result, five years later: While some districts get upwards of $8,000 per average attendee, others make do with less than $5,000.

“We supported the bill with the understanding that it was a first step,” said longtime education consultant Lynn Moak, whose firm, Moak Casey, represents some of the biggest school districts in the state. “We could see pretty clearly that the bill was going to have major problems in the future.”

The future turned out to be pretty near.

Wealthy districts tended to do better than their poorer counterparts. Take Alamo Heights Independent School District (ISD), a San Antonio school district so wealthy and white that it’s sometimes known as “Alamo Whites.” Based on estimates from Moak Casey, this district gets around $1,000 more per student than East Central ISD, a predominantly Hispanic district nearby. Logic would dictate that East Central needs more

money than Alamo Heights. If East Cen

ral were funded at the same rate as Alamo Heights, it would receive almost $6.5 million more than it currently gets. By and large, wherever school districts were frozen, there they remained. The formula system was all but dead since the “target revenue” system came into play. A 2009 measure put a moderate amount into formulas, but even now the vast majority of districts remain on target revenue. Those that have are the ones with the lowest target revenue numbers.

For example, in the Houston suburbs, Cypress-Fairbanks ISD is among the biggest in the state. With more than 127,000 weighted average daily attendees, Cy-Fair received a low target revenue number in 2006—and ever since has struggled to make ends meet. It’s one of the few school districts that post-2009 uses formula funding. Next door, Katy ISD gets around $600 more per average daily attendee than Cy-Fair. That may not sound like a lot, but it adds up to about $79 million the larger district isn’t getting.

Rural schools also face their share of inequity. Take Cochran County. There, Morton ISD has around 670 students, while Whiteface Consolidated ISD has almost 600. Whiteface’s students are worth almost double those in Morton, getting around $9,500 per weighted average attendee. Morton gets less than $5,200. School districts are allowed to raise property tax rates but that complicated system is a story of its own.

As news of education cuts spreads across the state, parents are coming out in force to protest—but often with little regard for how their districts’ funding compares with neighbors’. At the Save Texas Schools rally, Austin parents were out in force, though their district gets almost $1,000 more per weighted average kid than Fort Worth ISD. The districts are similar in size and need—but Austin has $95 million more to spend.

As Moak said, funding by target revenue amounts to “a clear declaration by the state that students in X district are worth less than students in Y district.”

(Based on the Sept 2010 estimates from Moak Casey consulting firm. WADA: weighted average daily attendance *dollar amount per WADA)

“Many, many, many members have said on many occasions, ‘When and how are we ever going to get out of target revenue?’” So began another Senate school-funding hearing led by Sen. Shapiro. She led the fight in that chamber for the disastrous 2006 reforms. But Shapiro, like a growing number of legislators, acknowledges the unfairness built into the system she helped create. If anything positive comes out of the state’s fiscal crisis, it’s possible that the system might become fairer over the long run—especially if those protesting budget cuts start advocating for systemic reform as well.

“Conventional wisdom is that it’s easier to be equitable when you’ve got a lot of money to work with,” McCown told me. “But here it may turn out that it’s actually easier to move toward equity when you don’t have money, when you’re distributing cuts.”

Until now, lawmakers had little incentive to fix the system. Because so few legislators understand the ins and outs of school finance, their chief concern is keeping their own districts happy. That’s not a recipe for good statewide policy. Thanks to the bizarre system that determined a school’s target revenue, many wealthy districts—like Alamo Heights in San Antonio or Highland Park in Dallas—are getting millions of dollars more than districts of similar sizes in other parts of the state. That’s fine and dandy with the folks in rich districts—and with their representatives.

“That’s probably one of the reasons we were unable to fix target revenue,” Sen. Duncan said. “There were some that were artificially high, [and] they didn’t want to change the system.”

Rep. Hochberg agreed: “The sponsors said, ‘Oh this is just temporary.’ Well, nothing’s temporary. Once you give somebody a level of funding, it’s very hard to lower it again.”

The budget shortfall may offer the first chance at returning most districts to a formula-based funding system. Hochberg, who fought a lonely fight against the 2006 reforms, has offered a bill making widespread cuts to education, but returning school districts to formula funding. All districts would be funded in a similar manner.

Hochberg’s bill probably won’t see the light of day. His bill hacks away at those districts living large on $10,000 per student. But his ideas are being discussed by Shapiro and other Republicans and Democrats, who are recognizing the opportunity to fix the mistakes of 2006.

“We can’t just pretend like the system is OK—because of the cuts, because of the shortfall,” said Lauren Cook at the Equity Center, an advocacy organization that represents 690 of the poorer school districts in the state. Cook said she hopes the state will “cut the target revenue” and work up a fair system that can be funded adequately once the state has money again. For goodness’ sake, she said, don’t cut from the schools at the bottom.

“Our fears are that the districts at the lowest levels of funding won’t get any help,” she told me. “The worst-case scenario is that they’re cut.”

Meanwhile, school districts plan for the worst and hope for the best. The commissioner of education already testified that he expects lawsuits from school districts. Districts won’t know their bottom lines until the Legislature approves a school finance measure, but districts’ budgets for next year will soon be due. Teachers are already bracing for pink slips, and parents are worried about school closures. The lawmakers are almost as scared—if there’s one thing the anger and turnout at the Save Texas Schools rally showed, it’s that cutting education will have political consequences.

There will be more such rallies, with messages even broader than just education. Don’t be surprised to hear a few more rounds of “fix our funding!” before the session’s over. If that becomes more than a slogan—if protesters, activists and legislators learn their school-funding ABCs—the fix could happen. What’s bad news for education funding in the next biennium could be good news for Texas schools for decades to come.

Learn more about Senate efforts to cut education costs through cutting state regulations.