Sarah Bird’s Lively New Novel Resurrects a Little-Known Civil War Hero

Bird produces a memorable re-creation of a freed slave who passed as a man to become a Buffalo Soldier — and of the thoroughly racist country in which she suffered and triumphed.

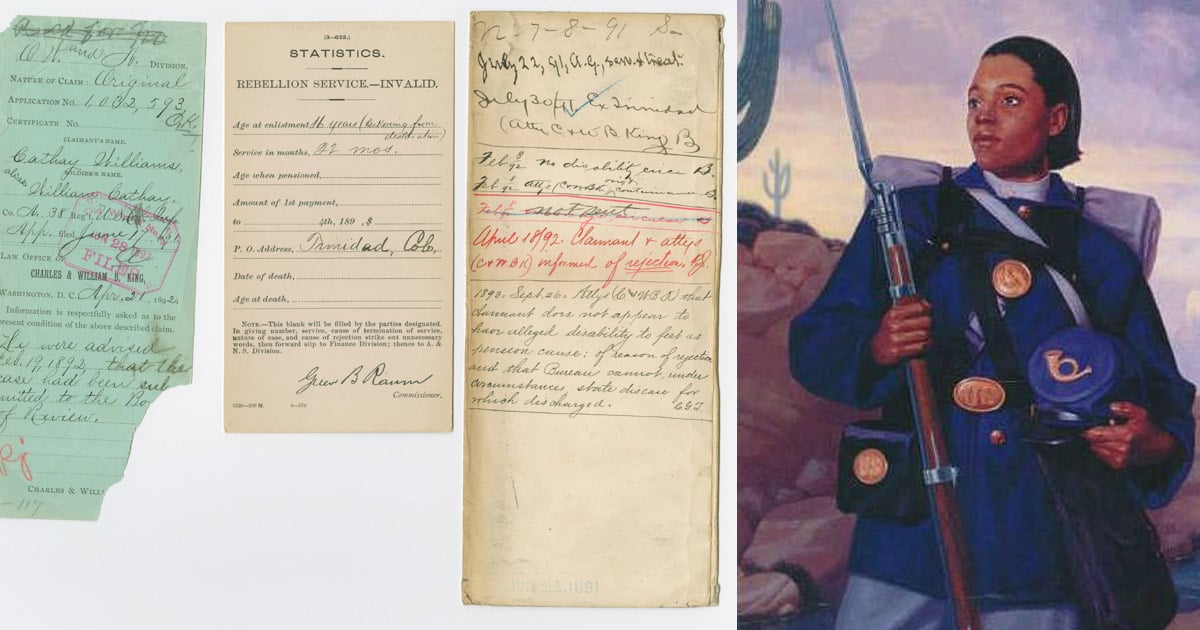

Above: Left: U.S. Army pension records for Cathy Williams. Right: Painting by William Jennings of Cathy Williams.

You want to use phrases like “ripping yarn” and “helluva story” for Sarah Bird’s new page-turner, but that makes Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen sound un-literary. It is, and isn’t — both in the best ways. This sweeping historical fiction spanning the Civil War to post-Reconstruction is nothing if not reader-friendly in a way that seems to call up the very power of the novel itself.

In Bird’s hands, the imaginative autobiography of Cathy Williams, a real-life freed slave who had to pass as a man to survive and to become a Buffalo Soldier, energetically pins the work to its Dickensian roots. Rather than an elitist conceit of style and cloistered meaning, Daughter leaps out as a shared experience between writer and reader as vital as that between movie screen and cheering audience at a Saturday matinee. It makes demands, as does good literature, but also is generous with rewards. Fleshing out a skeleton of facts about Williams’ life, Bird produces a memorable recreation not just of this barely known American hero, but also of the thoroughly racist country in which she both suffered and triumphed. Any echoes of that very same world reasserting itself today are purely coincidental.

St. Martin’s Press

$27.99; 416 pages

Bird’s long fascination with Williams extends her interest in penetrating other cultures, most recently that of Okinawa, Japan, in Above the East China Sea (2014). In this latest effort, Bird allies with what can only be celebrated as a marked turn in American fiction toward new and ennobling stories drawn from the horrific cauldron of slavery and its aftermath. If Williams’ journey at times seems to echo those of the protagonists in The Underground Railroad, The Good Lord Bird, A Shout from the Ruins and others, it’s because it wades the same waters.

Bird’s entry stands well for itself. One of its many strengths is simply seeing the unfolding of American history through the eyes of someone who could today be termed a subaltern teenage girl. Williams’ awareness of the evils of the Confederacy and Reconstruction form an ongoing subtext to the action-packed narrative of her own life as a “contraband” worker in the Union Army for General Phil Sheridan and later with the newly formed “Buffalo Soldiers” regiment of the 9th U.S. Cavalry. Her journey takes her through dramatic and often-deadly encounters, from Missouri’s “Little Dixie” to a decidedly unimpressed view of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox to the violent frontier West. All the while, she disguises her true identity to avoid rape and murder.

Part of Williams’ journey as she rides with the troops to Indian territory in the West goes through Texas, for which she had little affection, for good reason:

“It was odd, though, that the farther west into those piney woods we rode, the heavier grew the spell of the South that fell upon us. … That slavery times not only had never ended in east Texas but would go on for all eternity … The story passed among us that this state had fought not one, but two, wars, the first against the Mexicans who didn’t allow slavery, for the right to own us and build Texas off of free black labor. Then they fought with the confederacy to keep my people in chains. I figured this explained why the state seemed double haunted and double damned.”

There is some scholarship on Williams, including a 2002 biography, Cathy Williams: From Slave to Female Buffalo Soldier, by Phillip Thomas Tucker, and a few photographs. All research, like the novel, is drawn to Williams’ time with the Buffalo Soldiers, though some studies consider her time in slavery, the Civil War and her later years. The arc created by Bird follows the general, if sketchy, path of the real person. Although Williams is known to have lived in Colorado in her later years, there is no record of her after 1892.

As with all historical fiction, there is an implied acceptance of how closely the imagined version adheres to what really happened. Rarely can we ever know, so we rely on the intuition and honesty of the carrier of the tale. But there’s also another possibility: that the recounting creates a new dimension for people in our shared past who never got their due. Certainly Cathy Williams did not. And certainly she deserves to be brought full-born into our lives and our canon now.

As an epigram, Bird cites an observation from L. Frank Baum, who gave us Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz: “Girls want marvelous adventures just as much as boys do.” This is the power and meaning of Bird’s entire novel. Maybe her career.